| Environment |

|

|

|

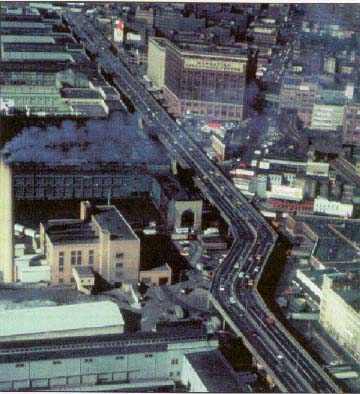

Aerial view of West Side Highway (looking South), circa 1970. |

Case StudiesROUTE 9 RECONSTRUCTIONBorough of Manhattan, New York, NY |

|

|

BACKGROUND/PURPOSE After more than 20 years of planning and design efforts, the reconstruction of what was formerly known as the West Side Highway has now begun. The project proposes to reconstruct State Route 9A from Battery Place to 59th Street along the western edge of Manhattan. This 5mile section of roadway lies at the southern end of New York State Route 9A, which begins at the BrooklynBattery Tunnel and extends northward for approximately 76 km (47.5 miles), until it merges with U.S. Route 9 in Peekskille, NY in northern Westchester County. Commonly known as West Street, Eleventh Avenue, Twelfth Avenue, the West Side Highway, or the Miller Highway, this portion of State Route 9A plays a vital role in the regional transportation system of the New York metropolitan area.

Previously, this portion of Route 9A comprised the West Side Highway, an elevated limitedaccess roadway originally constructed in the 1930's between the Battery and 72nd Street, and a service road and local service street beneath the elevated roadway terminating at 59th Street. After the collapse of a portion of the elevated roadway in the early 1970's, and in recognition of its overall deteriorated condition, the entire section of highway from the Battery to 59th Street was closed to traffic in 1974. The elevated structure was subsequently demolished in the late 1970's, and the existing atgrade roadway was repaved to serve as an interim roadway until a permanent replacement for the West Side Highway could be constructed. A proposal originally conceived in the early 1970's for the construction of a sixto eightlane interstate freeway facility known as Westway, which would have been partly elevated and partly depressed below grade, was withdrawn in 1985. The Westway funds were redistributed to several transportation projects in the city of New York, one of which was for the reconstruction of the interim roadway and its improvement into a permanent facility. The primary purpose of the Route 9A reconstruction project is to address the numerous problems and deficiencies associated with the continued use of the interim roadway and to accommodate some of the traffic that was diverted to other streets in the area when the elevated roadway closed.

The Route 9A facility serves a variety of regional, arterial, and local transportation activities and needs. It is an important interconnection between the BrooklynBattery Tunnel, the Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) Drive and the East River Bridges via the Battery Park underpass, the Holland Tunnel, the Lincoln Tunnel, and the West Side Highway/Henry Hudson Parkway, which provides access to the George Washington Bridge, the CrossBronx Expressway, and points north. The roadway is a major northsouth artery in Manhattan's street grid that serves through movements to and from the borough. It is also a local street that provides vehicular and pedestrian access to the activities, businesses, and residences that line its rightofway. The roadway also serves important intermodal functions by providing access to three Hudson River ferries, passenger liner terminals, excursion ships, and a heliport, and by serving as the terminus point for five crosstown bus lines. The existing traffic volumes on the roadway reflect Route 9As

importance in the region's transportation system. Route 9A serves

regional, arterial, local, and intermodal transportation functions.

Average daily twoway traffic volumes range from 69,000 to 81,000 vehicles.

With the closure and demolition of the elevated West Side Highway, the New

York City DOT estimates that as many as 10,000 vehicles per day have

diverted to Manhattan's other northsouth routes, further taxing the

capacity of these already congested roadways. ENVIRONMENTAL AND DESIGN ISSUES AND CONSTRAINTS In 1987, the city of New York and New York State established a joint West Side Task Force in an attempt to reach a consensus on what action should be taken to replace the deficient interim highway. The task force ultimately developed the concept of creating an atgrade sixlane urban boulevard as the most appropriate solution to the identified problems. The primary goals, objectives, and design principles developed by the Task Force formed the basis for the subsequent Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and project planning and design phases of the Route 9A project. The project encompassed the full gamut of issues and concerns associated with providing major improvements to an existing transportation facility in an established urban area. In addition to issues that are typically encountered in major improvement projects, such as potential impact on adjacent land uses (including parks and historic structures) and air quality and noise effects, a number of other considerations were addressed during the project planning and design process. These included the following:

ACTIONS TAKEN TO RESOLVE ISSUES AND CONSTRAINTS Recommended Design Concept The alternative ultimately selected through the EIS process is a basic sixlane urban boulevard with three travel lanes provided on either side of a raised, landscaped median. In a few locations, four travel lanes are provided along one side of the median area to better accommodate projected peakperiod travel demands.

A distinguishing feature of the final design is the use of barrier curbs that are .50 m to .85 m (20 in to 34 in) high along both sides of the center landscaped median and along the roadway edge with the riverside linear park. This higher harrier curb provides for substantially more soil around each tree and thus allows many more trees in total than would have been possible with a standard .15m to .20m (6in to 8in) urban curb. The latter curb height will be provided along the more developed east side of the new boulevard.

The facility will have 3.3m (11ft) travel lanes with .30m (1ft) offsets from the .50m to .85m (20in to 34in) barrier curb. The high barrier curb has been crash tested by FHWA Region 15 staff to a speed of 70 kph (45 mph) and is similar to that used on the Washington, DC area parkway system. The curb was selected as an alternative to the use of shoulders, which are preferred in the AASHTO Green Book for a facility of this functional classification and design speed. The new facility uses a design speed of 65 kph (40 mph) and will have a posted speed limit of 55 kph (35 mph), even though the project's functional classification as a principal urban arterial street would have allowed for a much higher design speed to be used. Detailed Traffic Analysis The traffic analysis performed as part of the EIS process was very detailed, and ultimately covered almost all of Manhattan. This analysis determined that virtually none of the users of the highway were traveling over its complete length, but rather using it to gain access to the eastwest street system on the island. The road thus operates, both today and in the future, as essentially a collectordistributor system between the BrooklynBattery Tunnel on the south and the elevated Henry Hudson Parkway on the north. To prevent the intrusion of through traffic into adjacent residential areas, a number of the originally proposed median openings will be closed, allowing only rightturn in and rightturn out movements between the northbound boulevard travel lanes and the eastwest street system. Pedestrian Movements Pedestrian movements back and forth across the highway were examined extensively. Indeed, one of the major design elements of the project is the integration of the highway improvements with the pedestrian crossings to the planned Hudson River Waterfront Park. In addition, a small existing city park at 23rd Street will be greatly expanded (ultimately to encompass more than a full city block) both as a new urban amenity and to provide improved traffic operations in this area. An associated feature is the use of a "bulbout" design along the east side of the highway at all intersections to better delineate the curb parking areas and to help minimize the pedestrian crossing distances across the travel lanes. These designs will be closely coordinated with the pedestrian crossing points on the landscaped median.

Separation of Pedestrian and Bicycle Traffic In this part of Manhattan, as in many urban areas, there are significant conflicts between pedestrians and bicyclists. A design element incorporated to alleviate this conflict along the river side of the boulevard is the provision of a separate 4.9mwide (16ft) bikeway for use by bicyclists and rollerbladers (both recreational and commuter) and a parallel 4.6mwide (15ft) pedestrian pathway-promenade. The Street Light Design Issue As the design concept moved into the formal preliminary and final design phases, a major issue that was successfully resolved concerned the design of the street lights along the project. The design of the standard New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT)/city of New York steel street light pole was deemed by community representatives to be out of keeping with the overall urban boulevard concept. After some additional research, it was discovered that the light poles that were being used in the privately developed Battery Park West (a mixeduse office/retail/residential development) were replicas of a design originally found throughout the city of New York in the early part of this century. This replica design is being incorporated along the length of the project.

Other Notable Design Elements No formal design exceptions were requested for this project by the New York State DOT. All the design elements are within AASHTO allowable ranges. Some of the special elements that have been incorporated into the final design of the project include the following:

LESSONS LEARNED This project has the potential for widespread application across the Nation as an illustration of the manner in which a collaborative, multidisciplinary planning and design process, incorporating a high level of continuous public involvement, can result in the creation of a worldclass street design. It also illustrates how detailed investigations of travel demand and traffic movement patterns can result in a dramatic change in the scale of the proposed improvement, from a six to eightlane elevated urban freeway to a sixlane urban boulevard with a design speed of 65 kph (40 mph).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|