Table of Contents

Page

Table of Contents............................................................................................................... 2

List of Figures..................................................................................................................... 4

List of Tables...................................................................................................................... 8

Foreward/Notice................................................................................................................. 9

Acknowledgement............................................................................................................. 10

Executive Summary.......................................................................................................... 11

1.

Introduction.................................................................................................................. 12

2. Project Tasks............................................................................................................... 13

2.1 Materials and Product Forms Technology........................................................ 13

2.1.1 Long Fiber Thermoplastic (LFT) Extrusion Trial

Runs......................... 13

2.1.2.. Thermoplastic Composite Pellet and

Tape............................................ 16

2.1.3.. Woven Broadgoods................................................................................. 17

2.2 Processing Technology...................................................................................... 20

2.2.1 Vacuum Assisted Resin Transfer Molding............................................ 20

2.2.2 Processing Woven Thermoplastic Broadgoods...................................... 33

2.2.3.. Mechanical Testing Results................................................................... 41

2.2.3.1 Tensile Data on Compression-Molded Panels-Effects of Test

Sample Width........................................................................... 41

2.2.3.2 Polypropopylene/Glass Impact

Investigations-Gas Gun,

Falling Dart, and Izod

Tests.................................................... 42

2.2.3.3 SMA/Glass Mechanical Tests Results................................... 53

2.2.3.4 Polyurethane/Glass Panel Impact Results.............................. 55

2.2.4 Fire Safety of Flooring............................................................................ 55

2.3 Joining Studies................................................................................................... 59

2.3.1 Lap Shear Tests of Neat Polymer.......................................................... 59

2.3.2 Surface Roughness Effects on Joining................................................... 62

Table of Contents

Page

2.3.2.1.. Materials and Experimental Procedure.................................. 63

2.3.2.2.. Experimental Procedure for Surface

Roughness................... 63

2.3.3 Single-Lap Shear Tests........................................................................... 66

2.3.4 The Effect of Release Agent on Single-Lap Shear Strength................. 68

2.3.5 Lap Shear Testing of Ultrasonically Bonded Samples.......................... 69

2.3.6 Thermoplastic Joint Impact Tests.......................................................... 70

2.3.7 Joining Conclusions................................................................................. 73

2.4 Tooling Development.......................................................................................... 74

2.5 Design, Analysis, and Testing of Bus Flooring Module.................................... 82

2.5.1.. American Public Transportation

Association Floor Part

.......... Guidelines................................................................................................ 82

2.5.2.. Design Concepts..................................................................................... 88

2.5.2.1 Balsa Core and Face Sheets.................................................... 88

2.5.2.2 Sine Core Design..................................................................... 89

2.5.2.3 Isogrid Design Analysis........................................................... 91

2.5.2.4 Flattened Sine (Hat)................................................................. 93

2.5.2.5 Processing Consideration and Shape Efficiency..................... 98

2.5.3 Component Testing and Analysis......................................................... 108

3.

Future Work............................................................................................................... 123

References...................................................................................................................... 124

Appendix ........................................................................................................................ 125

Glossary and Abbreviations........................................................................................... 127

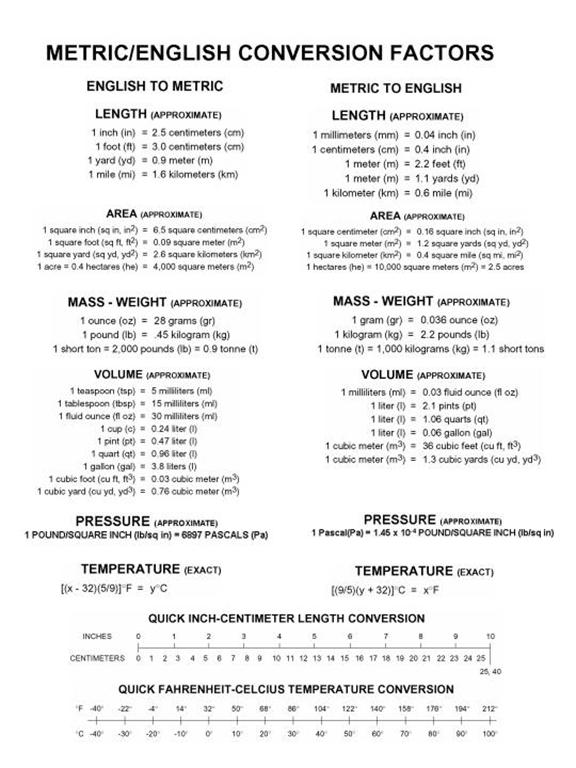

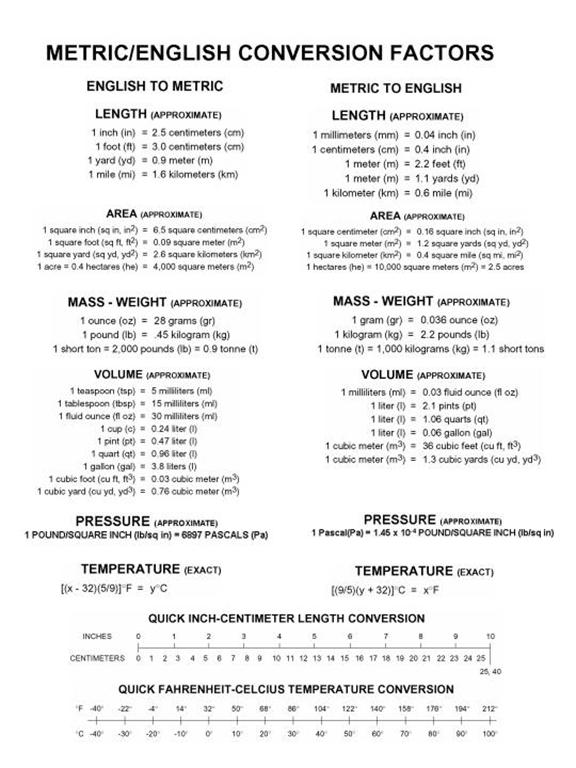

Metric Chart................................................................................................................... 129

List

of Figures

Figure Page

2.1.1-1 ..... Extrusion

Die with Heating Elements in Zones 1, 2, & 3 and Cooling Lines in Zone 4 13

2.1.1-2 ..... Extruded

PP/glass LFT................................................................................. 14

2.1.1-3 ..... Temperature Gradient across the

Extrusion Die

................... Heating/Cooling

Zones.................................................................................. 15

2.1.1-4 ..... Fiber

Condition after Flat Sheet Extrusion from Burn-out Sample............ 16

2.1.3-1 ..... Roll

of Woven Polypropoylene/E-glass Fabric............................................ 17

2.1.3-2 ..... Close-up

View of Woven Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric............................. 18

2.1.3-3....... Consolidated Sheet of Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass................................ 18

2.1.3-4....... Close-up of Consolidated Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass........................... 19

2.2.1-1....... Low Cost VARTM Processing..................................................................... 20

2.2.1-2 ..... Illustration

of FASTRAC Process for Rapid Processing............................ 22

2.2.1-3 ..... High

Temperature Set-up for Nylon VARTM Processing......................... 23

2.2.1-4 ..... The High Temperature Processing Set-up................................................... 24

2.2.1-5 ..... Various

Stages of Processing of FASTRAC Processing............................. 25

2.2.1-6 ..... Wet

Out Characteristics of Nylon to E-glass Fiber..................................... 26

2.2.1-7 ..... Carbon

Fiber Preform Bagged under Vacuum and Prepared for Insulation with Caprolactam 27

2.2.1-8 ..... Resin

Infusion of Caprolactam in Progress................................................. 28

2.2.1-9 ..... High

Temperature VARTM Set-up............................................................. 28

2.2.1-10 .... Details of Heating and Mixing Unit

for Caprolactam................................. 29

2.2.1-11 .... Scanning Electron Micrograph Showing

Cross-Section and Wet-out of Nylon/Carbon Composite Plate Processed under VARTM

(2500 X)................................................... 30

2.2.1-12 .... Scanning Electron Micrograph Showing

Cross-Section and Wet-out of Nylon/Carbon Composite Plate Processed under VARTM

(8000 X)................................................... 30

2.2.1-13 .... Scanning Electron Micrograph Showing

a Section Parallel to the Fibers and the Wet-out of Nylon to E-glass Composite

Plate Processed under VARTM (2500 X)................... 31

2.2.1-14 .... Different Scanning Calorimetry

Comparison of Commercial Nylon (upper panel) and Nylon Produced with VARTM

Process................................................................................... 32

2.2.2-1 ..... Roll

of Woven Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric.............................................. 34

2.2.2-2 ..... Close-up

view of Woven Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric.............................. 34

2.2.2-3 ..... Consolidated

Sheet of Woven Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric..................... 35

2.2.2-4 ..... Close-up

of Consolidated Woven Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric................ 35

2.2.2-5 ..... Loom

Weaving Thermoplastic Prepeg......................................................... 36

2.2.2-6 ..... Take-up

Accumulator for Woven Prepeg Fabric......................................... 37

2.2.2-7 ..... Schematic

of Double Belt Press................................................................... 37

2.2.2-8 ..... Aluminum

Mold Half Showing Inserted Cartridge Heaters....................... 38

2.2.2-9 ..... Mold

Prepared for Vacuum Bag Thermoforming........................................ 39

2.2.2-10 .. Preparation

for Part Bonding with Low Melt Adhesive.............................. 40

2.2.2-11 .. Placement

of Secondary Part of Flooring Subcomponent to be Adhesively Bonded 40

List

of Figures

Figure Page

2.2.3.1-1 .. Ultimate

Tensile Strength as a Function of Specimen Width and Orientation 41

2.2.3.1-2 .. Modulus

as a Function of Specimen Width and Orientation....................... 42

2.2.3.2-1 .. Typical

Force-Time-Energy Curve for LVI of LFT Glass/PP Plate........... 44

2.2.3.2-2 .. LVI

to LFT Glass/PP Plate, Impact Side and Tensile Side............................. 45

2.2.3.2-3 .. LVI

to LFT Glass/PP Plate, Fracture Path and Fiber Pull-out........................ 46

2.2.3.2-4 .. Gas

Gun Test Apparatus.............................................................................. 46

2.2.3.2-5 .. Energy

Absorption vs. Areal Density for Three Samples........................... 47

2.2.3.2-6.... Sample 020919-1-38b Showing IVBOI

without Penetration....................... 47

2.2.3.2-7.... Sample

020919-1-33b Showing IVBOI without Penetration....................... 48

2.2.3.2-8 .. Sample 020919-1-01b Showing IVBOI with Penetration............................. 48

2.2.3.2-9 ... Sample 020919-1-65b High-Speed Image of the

Onset of Damage........... 49

2.2.3.2-10 Sample

020919-1-65b High-Speed Image Showing the Perforation of the Sample 49

2.2.3.2-11 Sample

020919-1-34b Impacted with a 100g (38.1mm f) /sabot at 53.1 m/s 50

2.2.3.2-12 SEM Normal to the Fracture Surface of

Sample 020919-1-34b Showing Fiber Pullout, Matrix Crazing, and Fiber Fracture.......................................................................... 51

2.2.3.2-13.. SEM

Normal to the Fracture Surface Showing Fiber Pullout, Matrix Crazing, and Fiber

Fracture 51

2.2.3.2-14.. SEM

Normal to the Fracture Surface of Sample 020919-1-39b after an IVBOI Test 52

2.2.4-1....... Critical

Points of Flame Retardancy Function............................................. 56

2.2.4-2....... Several

Flame Retardants and Respective Modes of Operation.............. 56

2.2.4-3....... Sample

of 40 Weight Percent Glass Composite without Flame Retardant after Dynatup

Impact Testing........................................................................................................... 57

2.2.4-4....... Sample

of 40 Weight Percent Glass Composite without Exolit AP751 after Dynatup Impact

Testing........................................................................................................................ 58

2.3.2.2-1.... Unsealed

Example of Surface Roughness Amplitude................................. 64

2.3.2.2-2.... Surface

Roughness Profiles of FRP (with Medium Vf)............................... 65

2.3.5-1....... Schematic

of Ultrasonic Welding Instrument.............................................. 69

2.3.5-2....... Comparison

of Single-Lap Shear Strength of FRP/FRP Bonded by Adhesive DP 8005 and

Ultrasonic Welding.......................................................................................................... 70

2.3.6-1....... The Schematic of the Samples for LVI Test................................................ 72

2.3.6-2....... Comparison

of Impact Resistance of Bonded Samples.............................. 73

2.4-1 ......... Assembly

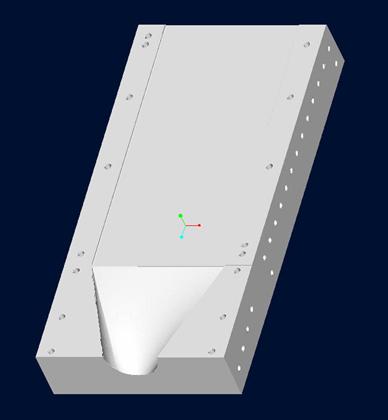

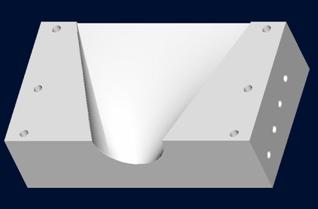

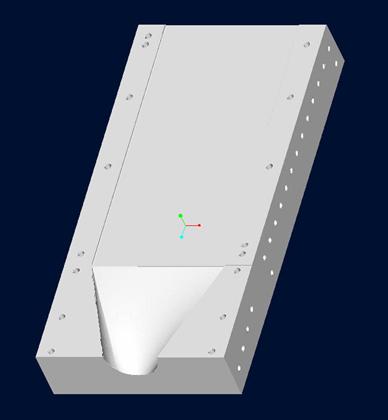

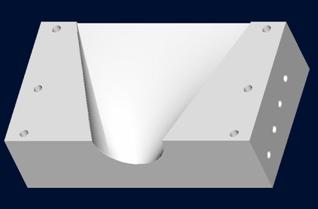

Drawing of the Die with the four Heating Zones Noted............. 74

2.4-2.......... Bottom

Die Assembly (Cavity Visible)........................................................ 75

2.4-3.......... Solid

Model of Identical Parts A and B....................................................... 75

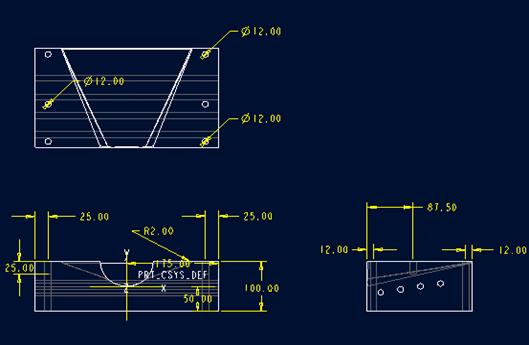

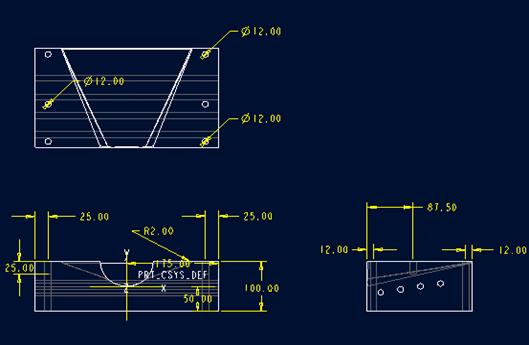

2.4-4.......... Dimensions

of Identical Parts A and B........................................................ 76

2.4-5.......... Solid

Model of Parts C and D....................................................................... 76

2.4-6.......... Dimensions

of Parts C and D....................................................................... 77

List

of Figures

Figure Page

2.4-7.......... Cross-section

View Showing Thermocouple Wells and Heater Holes....... 77

2.4-8.......... Placement

of Heating/Cooling Channels in Part C and D........................... 78

2.4-9.......... Picture

of Part A of Extrusion Die During Fabrication............................... 79

2.4-10........ Drawing

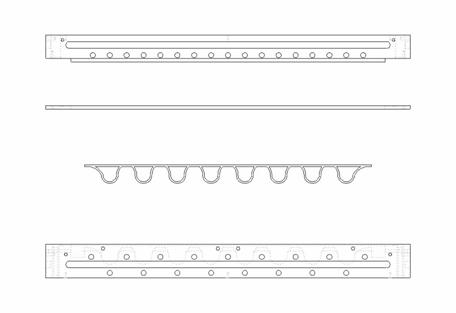

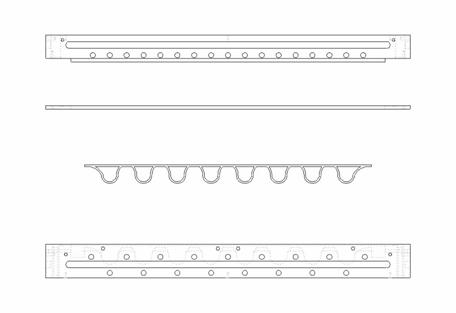

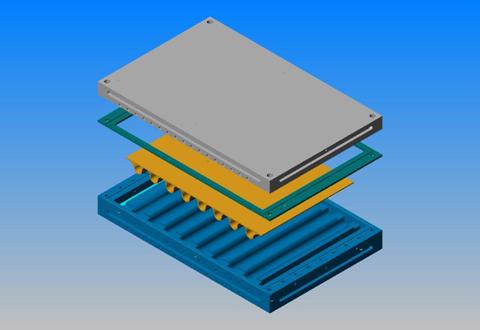

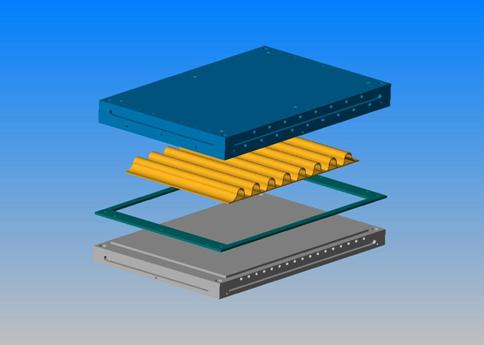

of the Bus Floor Subcomponent Design........................................ 80

2.4-11........ Line

Drawing of Part and Tool for Bus Flooring Subcomponent................ 81

2.4-12........ Exploded

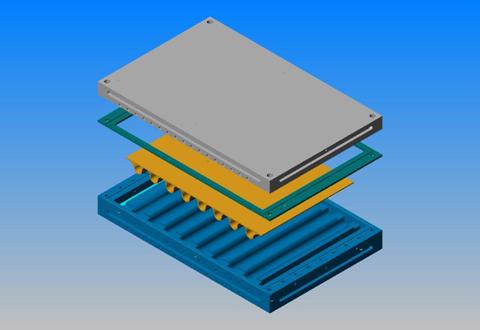

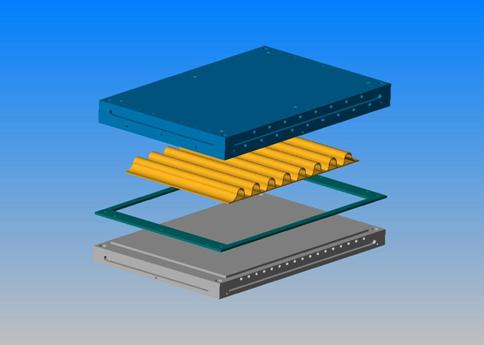

View of Tooling Design Including Steel Shim and Part.............. 81

2.4-13........ Inverted

Exploded View of Tooling and Part............................................... 82

2.5.1-1....... NABI

Conventional Bus Floor..................................................................... 84

2.5.1-2....... Close-up

of Conventional Bus Floor............................................................ 85

2.5.1-3....... Steel

and Plywood Floor used on Conventional Bus Floor.......................... 86

2.5.1-4....... Unit

Cell of Conventional Bus Floor............................................................ 86

2.5.1-5....... Dynamic

Modes of Typical Bus Structure................................................... 87

2.5.2.1-1.... Carbon/Nylon

(VARTM) Sandwich Composite with Balsa Core............... 88

2.5.2.1-2.... Glass/polypropylene

(Thermoformed, extruded) Sandwich

Composite with Balsa Core 88

2.5.2.1-3.... Stress

Development Balsa/Glass Sandwich Composite.............................. 89

2.5.2.2-1.... General

Concept of Sine Wave and Deck Plate Bus Floor Design............ 90

2.5.2.2-2.... Definition

of Dimension for Sine Wave Panel............................................. 90

2.5.2.2-3.... Illustration

of Composite Layup................................................................... 90

2.5.2.2-4.... Deflection vs. Wavelength for the

Sine Model........................................... 91

2.5.2.3-1.... Isogrid

Panel Design Elements.................................................................... 92

2.5.2.3-2.... Isogrid

Panel Design Parameters................................................................. 92

2.5.2.4-1.... General Schematic of Flattened Sine

Structure.......................................... 93

2.5.2.4-2.... Illustration of Design Parameters

that can be Optimized........................... 93

2.5.2.4-3.... Schematic Model of Flattened Sine

Layup Sequence................................. 93

2.5.2.4-4.... Comparison of Maximum Deflection for

Sine-Hat Models as a Function

................... of

Height, Wavelength, and Contact Distance............................................ 94

2.5.2.4-5.... Comparison of Maximum Stress for

Several Sine-Hat Models as a

................... Function of Height, Wavelength, and Contact

Distance............................ 95

2.5.2.4-6.... Principal Stresses Distribution for

Sine-Hat 6............................................. 95

2.5.2.4-7.... Principal Stresses Distribution for

Sine-Hat 10........................................... 96

2.5.2.4-8.... Dimensions for Model Sine-Hat 6................................................................ 96

2.5.2.4-9.... Dimensions for Model Sine-Hat 10.............................................................. 97

2.5.2.5-1.... Shape Efficiency of Hat Stiffened

Structures (Budiansky et al, 1990)....... 98

2.5.2.5-2.... Concept Modified Sine-Hat Stiffened

Floor Part........................................ 99

2.5.2.5-3.... Parameters of the Sine Rib Structure

Studied for ANSYS....................... 100

2.5.2.5-4.... Details of Shell 99 Element used in

ANSYS.............................................. 101

2.5.2.5-5.... Laminate Sequence for Face and Rib

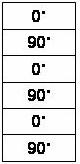

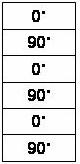

Plies-Woven Fabric Idealized as Cross-Ply 101

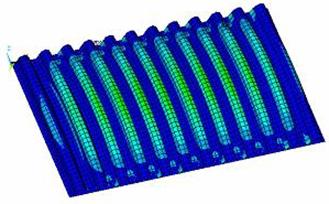

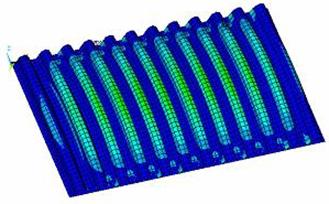

2.5.2.5-6.... Meshed Modified Sine-Hat Stiffened Floor Unit

Cell.............................. 102

2.5.2.5-7.... Boundary Conditions used in

Analysis-Simple Supported on Two Edges and Fully Fixed 103

List

of Figures

Figure Page

2.5.2.5-8.... Loading Conditions on Floor Unit

Cell....................................................... 104

2.5.2.5-9.... Stress and Deflection Profile for

6mm Face.............................................. 105

2.5.2.5-10.. Stress and Deflection Profile for 6mm

Face.............................................. 106

2.5.2.5-11.. Stress and Deflection Profile for 9mm

Face.............................................. 106

2.5.2.5-12.. Stress and Deflection Profile for 9mm

Face.............................................. 107

2.5.2.5-13.. Stress and Deflection Profile for 9mm

Face.............................................. 107

2.5.3-1....... Detailed Drawing and Finished

Part.......................................................... 109

2.5.3-2....... Component Testing-Load Frame and

Part Close-up Showing Support Frame 110

2.5.3-3....... Additional Component Test

Details, LVDT, and Load Frame................. 111

2.5.3-4....... Load-Deflection Curves Tested

Samples.................................................. 112

2.5.3-5....... Conventional Floor-Details of

Unit Cell and Cross0Section of the Three Major Elements 114

2.5.3-6....... Flattened Sine Composite Floor

Design.................................................... 115

2.5.3-7....... Details of Plywood and Welded

Frame Structure (Major Section of Conventional Floor 116

2.5.3-8....... Details of Sine-Hat Stiffened

Floor (Major Section of

Composite Floor 117

2.5.3-9....... Deflection Analysis Assuming Unit

Cell is Extended across Entire Width

................... of

the Floor.................................................................................................. 118

2.5.3-10..... Modularization Concept of Composite

Unit Cells making up Floor Structure 119

2.5.3-11..... Modularization Concept of Composite

Unit Cells making up Floor Structure, and Extending across Entire Width................................................................................................ 120

2.5.3-12..... Modularization Concept in

Longitudinal Directional, Incorporating Wires and Rod Routing 121

2.5.3-13..... Modularization Concept in

Longitudinal Directional, Incorporating Foam Filling for Sound and Vibration

Damping....................................................................................................... 121

2.5.3-14..... Modularization Concept in Integrating

Upper Frame Skeleton to Continue through Bottom Floor 122

List of Tables

Table Page

2.1.1-1 ..... Extrusion

Die Channels and Zones used for the First Two Trial Runs...... 14

2.1.2-1 ..... Additional

Combinations of Resin and Fiber for Thermoplastic Composite Applications................... 17

2.2.1-1 ..... Summary

of Mechanical Tests on Carbon/Nylon Composite made by VARTM Process................... 33

2.2.3.2-1 .. Summary

of Falling Dart Impact Tests for Polypropylene/Glass............... 45

2.2.3.2-2 .. Intermediate

Velocity Tests on Polypropylene/Glass Panels..................... 50

2.2.3.2-3 .. Low

Velocity Impact Tests on Polypropylene/Glass Panels....................... 53

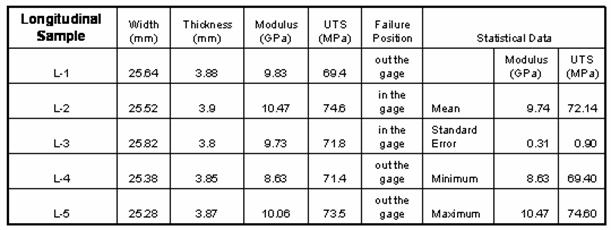

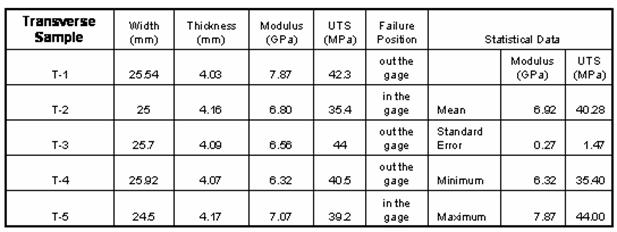

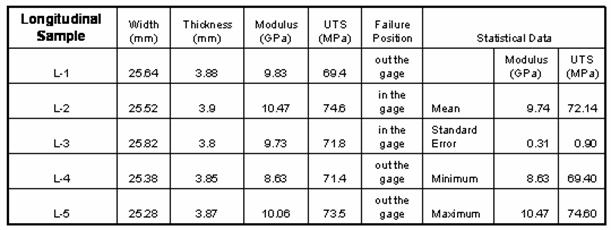

2.2.3.3-1 .. Unidirectional

SMA/glass Fiber Tensile Properties.................................... 53

2.2.3.3-2 .. Random

Fiber SMA/glass Tensile Properties-Longitudinal

................... Orientation..................................................................................................... 54

2.2.3.3-3 ... Random Fiber SMA/glass Tensile

Properties-Transverse

................... Orientation..................................................................................................... 54

2.2.3.3-4 ........................................... Low

Velocity Impact Data-SMA Random Panels...................................... 54

2.2.3.4-1.... Polyurethane/Glass Panel Impact

Results................................................... 55

2.2.4-1....... Flame Spread and Smoke Testing

Results.................................................. 58

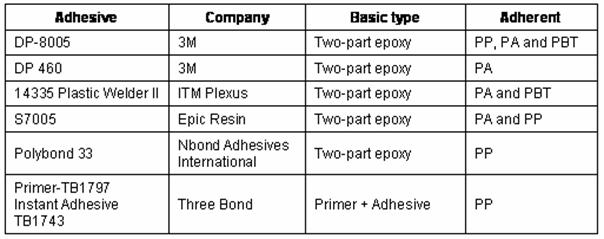

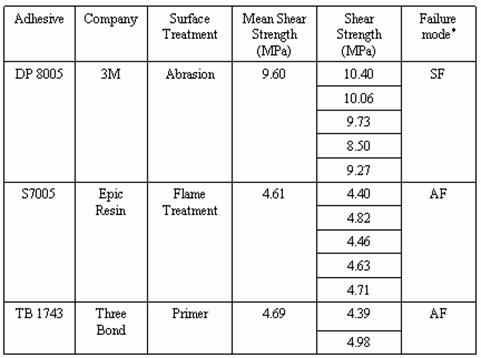

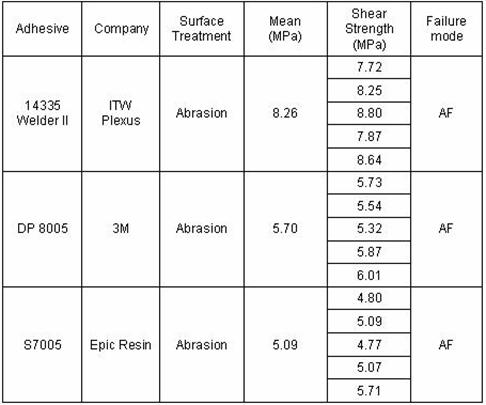

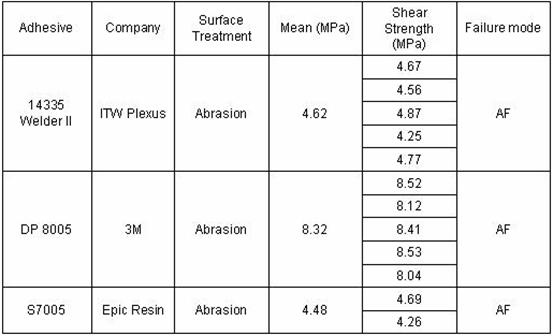

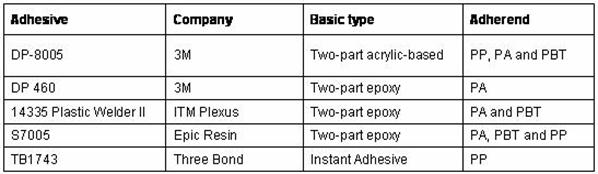

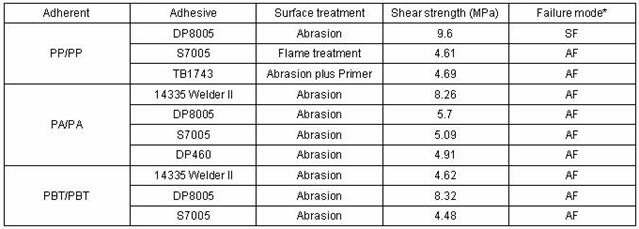

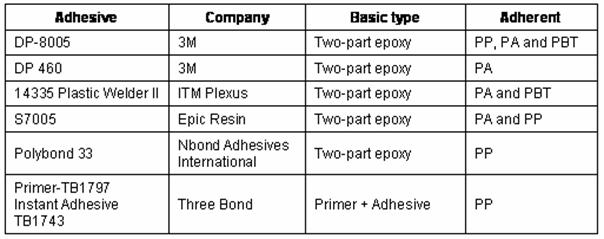

2.3.1-1....... Adhesive Candidates and Manufacturers................................................... 60

2.3.1-2....... Single-Lap Shear Strength of

PP-PP............................................................ 61

2.3.1-3....... Single-Lap Shear Strength of PA-PA........................................................... 61

2.3.1-4....... Single-Lap Shear Strength of

PBT-PBT...................................................... 62

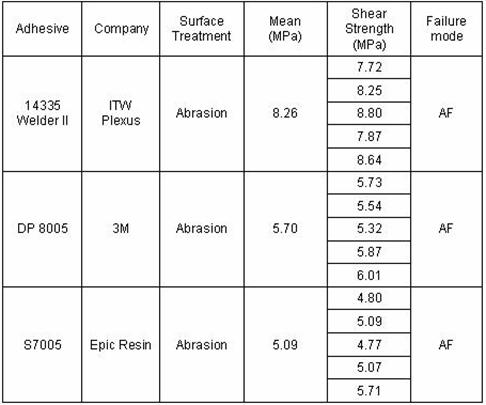

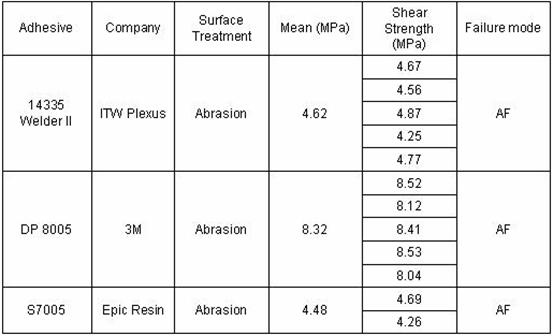

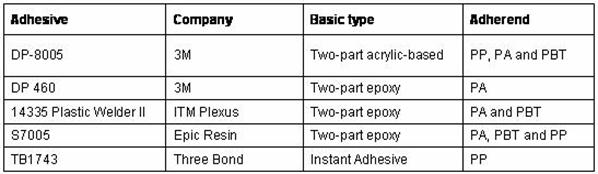

2.3.2.1-1.... Adhesive Candidates.................................................................................... 63

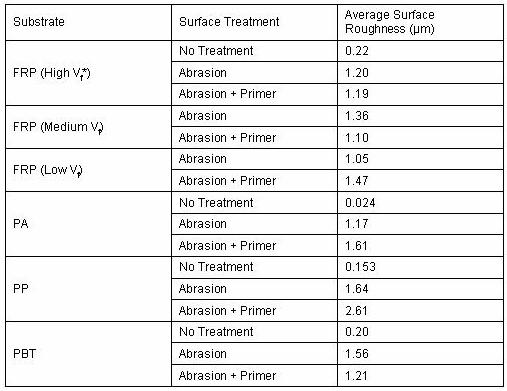

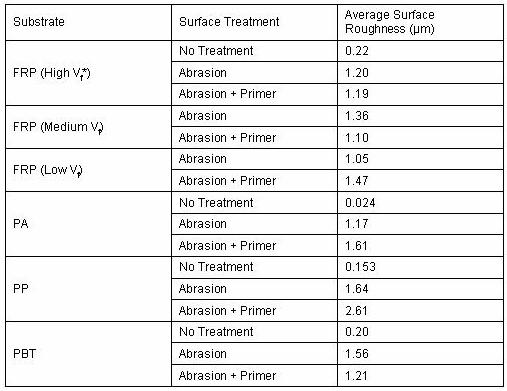

2.3.2.2-1.... Surface Roughness of Different

Substrates before and after Surface Treatment............................... 64

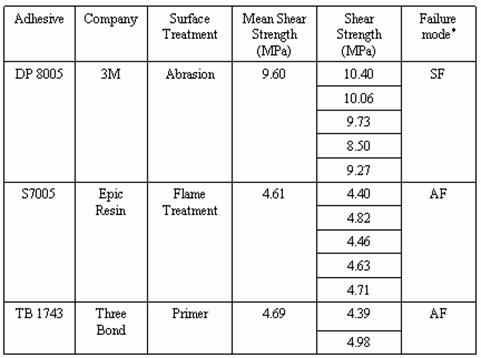

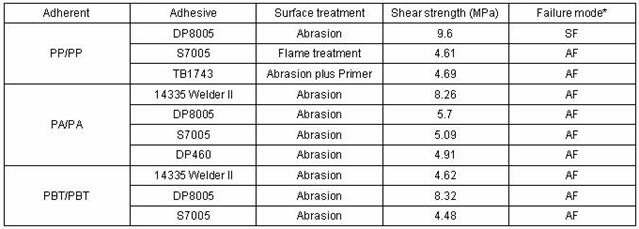

2.3.3-1....... Single-Lap

Shear Strength of PP/PP, PBT/PBT, and PA/PA...................... 66

2.3.3-2....... Single-Lap

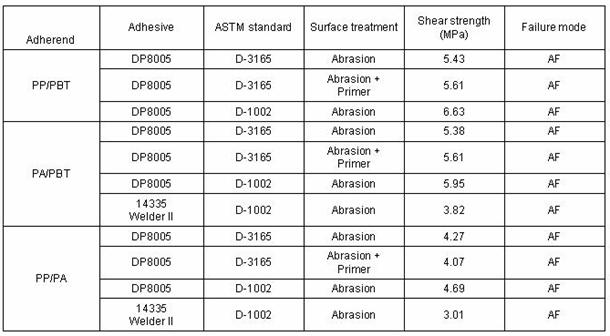

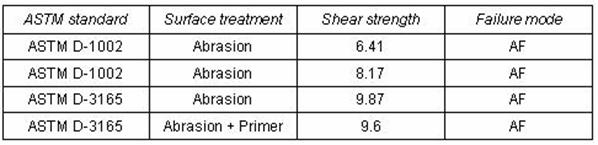

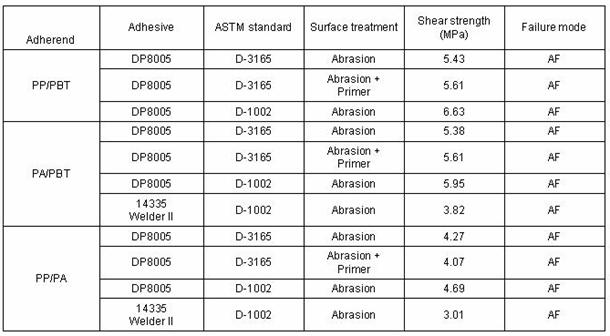

Shear Strength of Bonding of Dissimilar Polymers.................. 67

2.3.3-3....... Single-Lap

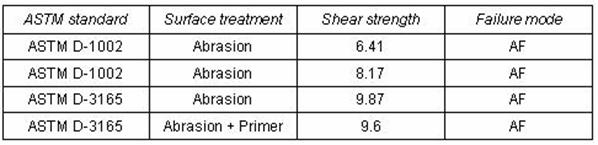

Shear Strength of FRP/FRP Bonded by DP8005..................... 67

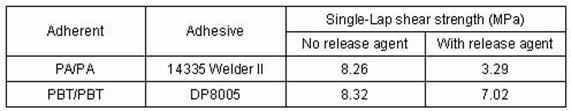

2.3.4-1....... Shear

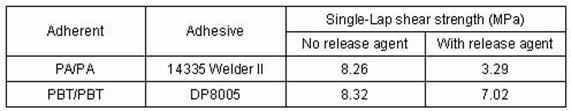

Strength Comparison with and without Release Agent.................... 68

2.3.5-1....... Effect

of Welding Setting on Shear Strength and Failure Mode of FRP/FRP...................................... 70

2.3.6-1....... Gas

Gun Impact Test Results of Adhesively Bonded Samples.................. 71

2.5.2.2-1.... Parameter Combinations for Various

Sine Models..................................... 90

2.5.2.3-1.... Parameter Combinations for Several

Isogrid Models................................ 92

2.5.2.4-1.... List of Flattened Sine Ribbing

Variations.................................................... 94

2.5.2.5-1.... Parameters of the Sine-Hat Studied

for ANSYS Analysis........................ 100

2.5.2.5-2.... Material Properties for

Glass/Polypropylene used in Analysis................ 105

2.5.2.5-3.... Loading, Boundary Conditions,

Maximum Deflection and Maximum Stress........... 108

2.5.3-1....... Conventional Floor Unit Cell

Weight Calculations.................................... 113

2.5.3-2....... Composite Floor Weight

Calculation......................................................... 116

2.5.3-3....... Weight Calculations for Major

Section of Conventional Floor................. 117

2.5.3-4....... Weight Calculations for Major

Section of Floor made from Sine-Hat Stiffened Composite 117

Foreward

This component describes steps

required to apply the technology of long fiber and continuous woven

thermoplastic composites in transit bus flooring applications for the

Department of Transportation and the Federal Transit Administration. The goals of improved safety, reduced weight,

and lower cost are very important to the transportation industry. This report describes the design guidelines

and fabrication methods related to the thermoforming of long-fiber

thermoplastic composite flooring for transit bus application.

Notice

This document is disseminated

under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest

of information exchange. The United

States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof.

The United States Government does

not endorse manufacturers or products. Trade names appear in the document only

because they are essential to the content of the report.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to express their

appreciation to the Federal Transit

Administration for the support of this work.

We thank the C.A. Lawton Company for the use of their plastication

equipment and North American Bus Industries for their guidance in component

selection and design guidelines. We

acknowledge the following for their contributions to the technical effort of

this project: George Husman, Tim

Hartness, Uday Vaidya, Greg Janowski, Krish Chawla, Joel Dyksterhouse, Patric

Moriarty, Mike Dyksterhouse, Andy Grabany, Chad Ulven, Shane Bartus, and Brian

Pillay. We acknowledge and thank Lisa

White for her assistance with the preparation of reports.

Executive Summary

The primary work addressed during

this project was directed at the design, fabrication and testing of a bus floor

subcomponent. The principal objectives

associated with the bus floor project were safety, weight, and cost.

The primary safety issue

(excluding the sufficiency of the structure) is flammability and smoke

generation during potential fire incidents.

The use of topically applied fire retardant coatings appears to present

the best solution to mitigating flame spread and smoke production. The high percentage of fiberglass content (60

percent by weight) reduces the polymer available as potential fuel for a

fire. Discussions are ongoing with a

fire retardant supplier to optimize the use of surface-coated retardants to a

bus floor application.

The bus floor design and

prototype subcomponent saves an estimated 40 percent in weight using

polypropylene and E-glass as reinforcement fiber. The design was based on a flat panel bonded

to a flattened sine wave rib structure.

The design was sufficient to meet American Public Transportation Association (APTA) deflection

standards under maximum loading conditions.

It is expected that the integration of the floor with a sidewall and

frame design will likely yield additional weight savings and performance

improvements.

The prototype design saved

approximately 40 percent in cost.

Material cost savings are in excess of 50 percent. In addition to the basic cost advantage, the

lifetime of the floor is equal to the expected lifetime of the bus itself; that

is, about 12 years. Normal plywood based

floors are often replaced after about 6 years due to rotting caused by water

exposure. The replacement cost and

downtime would also be a savings, but was not calculated as part of this

analysis.

It is anticipated that further

development will be performed with a focus on integrating frame, sidewalls and

flooring. This system integration is

necessary to provide the best mechanical performance with the lightest weight

and lowest cost.

1. Introduction

The Federal Transit

Administration (FTA) has encouraged innovative technologies to be implemented

in mass transit applications, particularly when improvements in performance,

cost, weight reduction, or safety may be realized. The results of efforts made by Southern

Research Institute under FTA Project AL-26-7001-01 were directed to the

fabrication woven prepreg thermoplastic composite bus flooring subcomponents

with demonstration of several contributing technologies. The

previous Phase 1 effort was focused on material production and compression

molding fabrication methods. In the

Phase 1 work, a two-person bus seat was molded in one piece. This design yielded a 40 percent cost savings

and 30 percent weight reduction for a typical transit bus seat.

The choice of bus flooring as the

test subcomponent was based on the desire to fabricate a large-area,

weight-bearing structure that would potentially save considerable weight. Bus frame and side panels were also

considered; however, it was felt that the consideration of frame and side

panels should be handled in a more comprehensive future study in which the

surface finish of the side panels and the complex loading of the frame could be

properly addressed with an integrated design of flooring, frame and

panels. Primary considerations for the

flooring application were safety, weight savings to reduce fuel consumption,

and cost savings to encourage usage in commercial applications. The choice of bus flooring as a thermoplastic

composite application goal was the result of consideration of overall weight

reduction calculations for several candidate bus components. The primary selection issue was based on the

total weight of flooring installed on a standard transit bus as well as the

potential increase in functional lifetime over conventional flooring structures. Design, fabrication, and mechanical testing

of the flooring subcomponent are described in the following report.

2. Project Tasks

2.1 Materials and Product Forms Technology

2.1.1 Long Fiber Thermoplastic (LFT) Extrusion

Trial Runs

Two sets of extrusion trials were

executed with polypropylene/Glass (PP/Glass) LFT using a Southern Research

Institute (SRI) plasticator and an extrusion die fabricated at the University

of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)

Physics Department machine shop.

Temporary modifications were made to the plasticator that allowed

continuous flow of PP/Glass LFT melt in an extruder-like mode. The processing parameters recorded during the

first two trial runs provided information defining a processing envelope for

the extrusion of PP/Glass LFT.

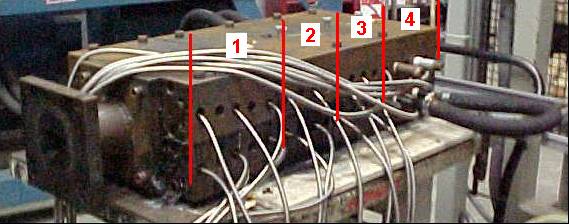

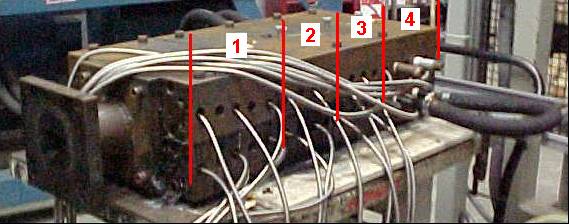

The die is composed of four parts

and a flange that are bolted together and then connected to the

plasticator. There are 18 dual purpose

through-channels on the top and bottom halves of the die for heat cartridges or

cooling lines (Figure 2.1.1-1). The

temperature of each of the four heating zones is maintained by an independent

temperature controller. Thermocouples

imbedded in the die provide each controller with precise temperature

measurement. The temperature of the

cooling lines was maintained with a remote water or oil cooling unit. The connecting flange to the plasticator is

not supplied with a heat source, but is well insulated and maintains a constant

temperature by conduction from adjacent zones and by convection of material

through it. The heating/cooling channels

are at a constant distance of 10 mm from the cavity wall. The distance between channels is 38mm from

center to center of the holes. Table

2.1.1-1 illustrates the channels used for the first two trial runs and the particular

heating and cooling zones adopted.

Figure 2.1.1-1 Extrusion Die with Heating Elements in Zones

1, 2, & 3 and Cooling Lines in Zone 4

Table 2.1.1-1 Extrusion Die Channels and Zones used

for the First Two Trial Runs

During the first trial run,

temperature of each zone was maintained at 232° C (Figure 2.1.1-1). The temperature maintained was higher than

the minimum melt temperature of the material.

This initial run demonstrated successful flow of PP/Glass LFT melt

through the die transition and into the rectangular die cavity shape (Figure

2.1.1-2). Material was permitted to flow

out of the die and into a cool water bath.

This initial trial run proved the feasibility process and provided process

temperature information to define the upper bound of the extrusion-processing

envelope.

Figure 2.1.1-2 Extruded PP/glass LFT

During the second trial run, the

temperature of each zone was adjusted to create a gradient along the length of

the die (Figure 2.1.1-3). The

temperature in Zone 4 (the exit zone) of the die was maintained with

water-cooling lines at 83° C, well below the melt temperature of PP/glass

LFT. The material leaving the die was

solidified in the shape of the die opening.

The low temperature in Zone 4 resulted in a very rapid melt

solidification that created a higher than desired backpressure in the

plasticator. The high backpressure

precluded a continuous process with this process configuration. The second trial run provided temperature

information for each zone that defined a lower bound of the

extrusion-processing process temperature envelope.

Figure 2.1.1-3 Temperature

Gradient across the

Extrusion Die Heating/Cooling Zones

With information

obtained from the first two extrusion trial runs, an approximate processing

envelope was defined.

Extrusion trials were conducted

with several feedstock approaches. The

initial feedstock was neat polymer BP/Amoco 9965. A mix of 50% 9965 and 50% Ticona pellet (40%

glass fiber) was tried next, followed by 100% Ticona 25.4 mm pellet. All systems were polypropylene/E-glass

combinations.

The best performance was obtained

with the 40% fiber since the effective viscosity was much higher than the neat

resin. The primary difficulty was that

the rate of flow of material and simultaneous maintenance of extrusion pressure

is neither linear nor constant. This

condition makes it very difficult to extrude anything other than short

discontinuous pieces and these with poor quality. A puller was used to assist with the panel

extrusion; however, the extrusion rate control and the force available on the

puller precluded production of a significant quantity of random fiber panel. The continuous production of random fiber

composite panels by extrusion appears promising, but additional equipment and

effort is required to achieve commercially acceptable panels. Samples of the panel were placed in an

air-atmosphere oven at 575° C to burn out the polymer matrix leaving the

fibers. Figure 2.1.1-4 shows the burnout

results from the extrusion panel that shows that the 25mm original fibers are

still intact after processing.

Figure 2.1.1-4

Fiber Condition after Flat Sheet Extrusion from Burn-out Sample

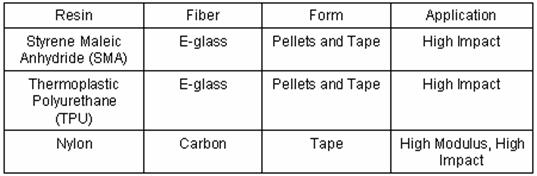

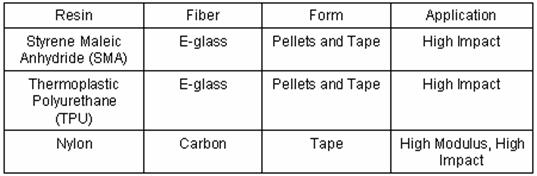

2.1.2 Thermoplastic Composite Pellet and Tape

Two additional polymers were used

to impregnate E-glass roving. These two

polymers were thermoplastic polyurethane, Pearlthane D11T75 (TPU) and modified

styrene SMA, Dylark 238. Tape products

were made from both materials and 25.4 mm pellets were made from the SMA

resin. Processing temperature for the

SMA was 250° C. Several hundred pounds

of the SMA pellets were produced for compression molding trials described in Section

2.2

Several different forms of

pellets and tape were produced to investigate potentially useful combinations

of E-glass and resins for transportation application. Table 2.1.2-1 lists several new forms and

possible application areas.

Table 2.1.2-1 Additional

Combinations of Resin and Fiber for Thermoplastic Composite Applications

Some of these materials have been

processed into panels and tested.

Testing results are in Section 2.2 of this report.

2.1.3 Woven Broadgoods

Polypropylene/E-glass tape was

produced in a 12.7mm width and then woven in to a fabric as shown in Figure

2.1.3-1. This material is about 1 meter

wide. A close-up view is shown in

Figure 2.1.3-2.

Figure

2.1.3-1 Roll of Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric

Figure

2.1.3-2 Close-up View of Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass Fabric

The woven fabric was processed in

a heated double belt press that consolidated the raw woven fabric into a dense

composite. A sheet of that material is

shown in Figure 2.1.3-3.

Figure

2.1.3-3 Consolidated Sheet of Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass

A close-up of the same material

is shown in Figure 2.1.3-4. The

consolidated forms can be used as-is as structural panels or can be

additionally formed in standard thermoforming operations.

Figure

2.1.3-4 Close-up of Consolidated Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass

The woven material can be vacuum

bagged, autoclaved or consolidated in a double belt press. The prototype bus floor subcomponent was

fabricated by vacuum bagging from this woven form of thermoplastic composite

material.

2.2 Processing Technology

A primary objective in the second

year of this effort for the Federal Transit Administration is the demonstration

of low-cost processing technologies for large-area transportation parts. Processes

discussed in the following sections included Vacuum Assisted Resin Transfer

Molding, thermoforming of woven broad goods,

and belt press consolidation of woven broad goods. Mechanical properties

of processed samples materials are presented.

2.2.1 Vacuum Assisted Resin

Transfer Molding

Recent developments in composites

processing methods have focused on cost-effectiveness and ability to produce

integrated structures using liquid molding techniques. Vacuum assisted resin transfer molding

(VARTM) has emerged as a leading cost-effective process that utilizes

innovative developments in one-sided tooling and vacuum-bag technology. VARTM is cost-effective because it eliminates

much of the tooling costs associated with high temperature and pressure cycle

operations incurred in an autoclave process environment. This process is a very attractive alternative

to spray-up or impregnation methods, and is far less expensive than

conventional manufacturing methods for production of a relatively small number

of parts, that is, less than 10,000/year. The VARTM process may be reduced to a

simple single-sided tooling that requires only consumables in place of

expensive molds. During the VARTM

process, resin is infused into dry fabric preform placed in single-sided

tooling that covered with an inexpensive vacuum bag film as illustrated in

Figure 2.2.1-1.

Figure 2.2.1-1 Low Cost VARTM

Processing

A distribution mesh aids in

distributing the resin evenly over the fiber preform. Large structural parts with inserts or

multiple layers can be produced rapidly.

In multi-layered constructions, the VARTM process can be effectively

utilized to produce parts by co-injecting resin to cause simultaneous part

wet-out. Other advantages of VARTM are

low process volatile emissions, higher fiber-to-resin ratios and good

repeatability. While most studies have

considered VARTM for thermoset type systems, similar processing of

thermoplastics has been limited to their inherently high viscosity. For VARTM to work successfully, the resin

must lie in the 100-500 cps viscosity range.

In the present work we are developing research thrust in VARTM

processing of thermoplastic composites.

To our knowledge, this will be a pioneering effort if proven successful

and will enable integrated processing of large flat shapes, as well as preform

with integrated joints. For

transportation applications, this can be used to rapidly manufacture floor

structures, large side panels and roof structures.

The objective of this work was to

enhance speed of processing to accommodate the narrow processing window for the

polymerization of thermoplastic resin systems.

Most thermoplastic resin precursors have a high viscosity (>1000

centipoise) and a very short working time. The normal VARTM process using a

distribution mesh cannot be used for thermoplastics because of the high

temperature requirement and poor surface finish.

The process has been developed by

the Army Research Laboratory for thermoset vinyl ester family of resins to

produce structures such as armored vehicle hulls. Some benefits are reduction

of scrap and 100% compatibility with current ground vehicle processing

methods.

A cross section of the process is

shown in Figure 2.2.1-2. The idea is to set a double vacuum bag. The top bag covers a channeled tool which is

placed over the bottom bag that holds the plies under vacuum. Applying a vacuum

between the two bagging materials causes the bag at the top surface of the

plies to be pulled towards the channeling of the tool. This causes channels

wide enough for the resin to race through. Once the resin reaches eighty

percent of the distance of infusion, the

channeled tool and the top bagging is removed. The vacuum now pulls the bagging

tight over the plies helping to wet out the plies. This process provides significant time

efficiency and ability to produce/process very large flat shapes. Figure

2.2.1-3 shows the setup for Nylon VARTM processing and Figure 2.2.1-4 shows

high temperature processing VARTM setup.

Figure 2.2.1-2 Illustration of

FASTRAC Process for Rapid Processing

Figure 2.2.1-3

High Temperature Set-up for Nylon VARTM Processing

Figure 2.2.1-4 The High Temperature Processing Set-up

The FASTRAC processing system has been successfully

implemented using higher viscosity thermoset resins, with very short gel times.

We optimized the spacing and dimensions of the channels for use in reactive

Nylon 6 resin.

The candidate thermoplastic

resins Nylon 6 and cyclic polybutylene terephthalate (c-PBT) polymerize at

temperatures of between 100 to 200° C.

Therefore, a controlled high temperature processing set-up for VARTM was

developed that addressed the issue of moisture sensitivity during the

polymerization. The actual trials were

conducted with the Nylon 6 system due to the very high cost of the c-PBT precursor

system.

A high temperature-processing

table for VARTM was developed using an industrial scale grill. The tool surface is heated using four

electric elements at 20kw. A 10mm aluminum plate, wired with thermocouples was

fixed to the top of the grill. This permitted uniform heating and accurate

temperature measurement of the tool surface. Tool surface temperatures of up to

230° C were achieved. An intelligent

control system was developed to achieve better temperature consistency. A display of the high temperature-processing

table and resin flow paths are shown in Figure 2.2.1-5. An example resin wet-out of Nylon 6 on

E-glass fabric was demonstrated and illustrated in Figure 2.2.1-6. This particular demonstration shows that large

structures can be fabricated with this technique.

Figure 2.2.1-5

Various Stages of Processing of FASTRAC Processing

(a) Bagged preform, showing

infusion channels, and

(b) Flow of resin through the channels

Figure 2.2.1-6 Wet Out Characteristics of

Nylon to E-Glass Fiber

The Nylon 6 system under

evaluation consists of caprolactam monomer using Brüggolen C10 catalyst and

Brüggolen C20 activator (Brüggemann Chemical U.S., Inc.

Newtown Square, PA). The manufacturer’s

guide specified using 1.2% to 3% catalyst and 1.0% to 2.5% activator in an

inert atmosphere. Success was achieved

with carbon fabric using the following process:

·

Teflon tubing was slit and used for resin

distribution over the width of the preform.

·

Layers of 210 x 210mm de-sized (acetone

extraction) woven carbon fabric was used in the lay-up.

·

The woven carbon preform was vacuum bagged on a

heated processing table. High temperature bagging materials and sealant tape

were used to seal the preform.

·

The caprolactam (200g) plus activator (3g) was

heated at 75° C in an oil bath until it reached a fully liquid state. The

solution was continuously agitated using a mechanical stirrer.

·

When the entire solution was in a liquid form,

the catalyst (6g) was added to the solution.

·

Dry nitrogen was used to continuously purge the

system to prevent any moisture from getting into the flask.

·

The carbon lay-up was heated to 120° C and

purged using dry nitrogen.

·

The resin was then infused into the preform.

·

After the resin filled the

perform, the temperature of the heated table was raised to 150° C to

complete the polymerization.

Figures 2.2.1-7 through 2.2.1-10

illustrate the VARTM process with carbon cloth reinforcement.

The primary needs in a stable

Nylon VARTM process are uniform process temperature and moisture-free

atmosphere in all stages of the process.

Deviations in either of these areas will result in poorly polymerized

product and difficulty with uniform resin infusion.

Figure 2.2.1-7 Carbon Fiber

Preform Bagged under Vacuum and

Prepared for Infusion with Caprolactam

Figure 2.2.1-8 Resin Infusion of Caprolactam in Progress

Figure 2.2.1-9 High Temperature VARTM Set-up

Figure 2.2.1-10 Details of Heating and Mixing Unit for

Caprolactam

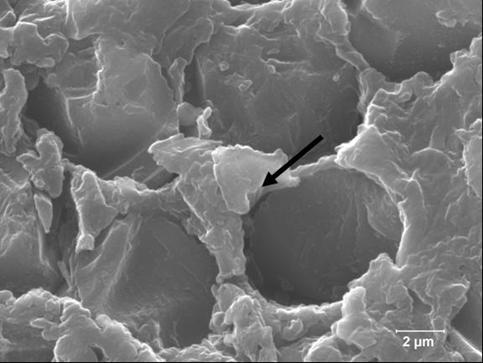

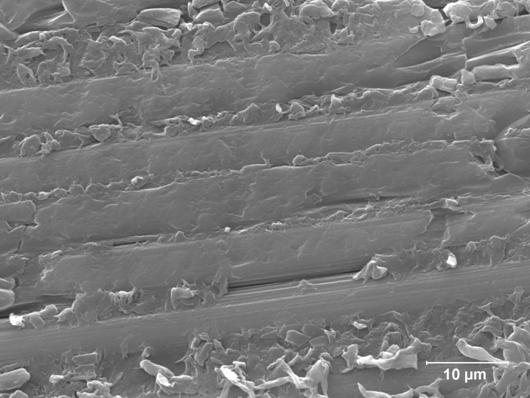

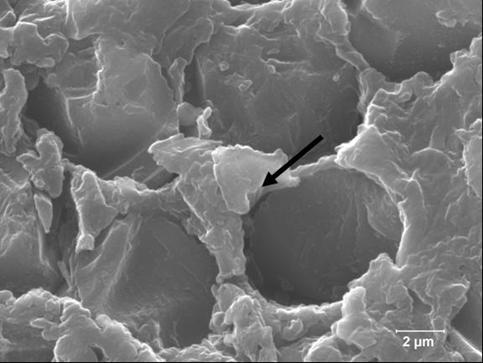

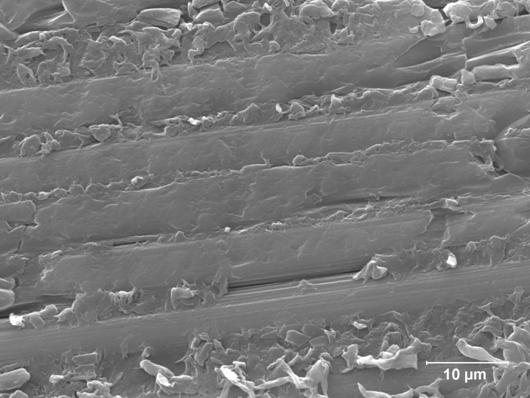

Figures 2.2.1-11 through 2.2.1-13

show high magnification cross-sections perpendicular and parallel to the fibers

that illustrate that adequate wet-out throughout-the-thickness was obtained

during the VARTM process. Some

filament level voids were observed typical of the microstructure developed

during a VARTM process.

Figure 2.2.1-11 Scanning

Electron Micrograph Showing Cross-Section and Wet-out of Nylon/Carbon Composite

Plate Processed under VARTM (2500 X)

Figure 2.2.1-12 Scanning

Electron Micrograph Showing Cross-Section and Wet-Out of Nylon/Carbon Composite

Plate Processed Under VARTM (8000 X)

Arrow Shows Areas of Highly Crystallized Nylon

Figure 2.2.1-13 Scanning

Electron Micrograph Showing a Section Parallel to the Fibers and the Wet-Out of

Nylon to E-Glass Composite Plate Processed Under VARTM (2500 X)

Additionally, Figure 2.2.1-14

shows the contrast of the two differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) runs

comparing a commercial grade of Nylon and the Nylon produced by the VARTM

process. The narrower peak of the VARTM

process indicates narrower molecular weight distribution and higher

crystallinity.

Figure 2.2.1-14 Differential

Scanning Calorimetry Comparison of Commercial Nylon (upper Panel) and Nylon

Produced with VARTM Process

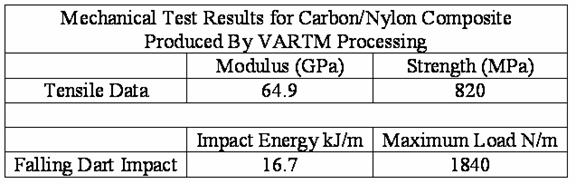

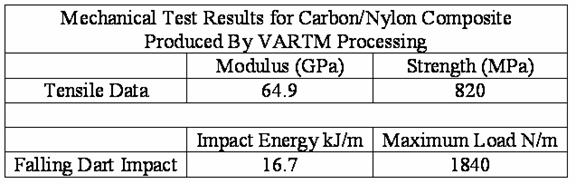

Mechanical testing data have been

generated on the Carbon/Nylon VARTM process.

The carbon fiber content of this test sample was 66 percent by weight

and 50 percent by volume. Table 2.2.1-1

summarizes the tensile and falling dart impart data.

Table 2.2.1-1

Summary of Mechanical Tests on Carbon/Nylon Composite made by

VARTM Process

The mechanical properties of the

carbon/nylon composite are encouraging for practical use. The tensile modulus and strength were close

to theoretical for a two dimensional orthotropic carbon composite. The falling dart impact data was indicative

of excellent energy absorption for low velocity projectiles.

2.2.2 Processing Woven Thermoplastic Broadgoods

The use of woven thermoplastic

composite broadgoods is an efficient method for laying up a substantial area

and thickness of composite for processing in a thermoforming environment. An important requirement for the effective

thermoforming with vacuum bag or double belt press is that the prepreg tape

used to weave the fabric must be evenly and completely wet-out by the

resin. The degree wet-out of the fiber

by the resin is dependent on the compatibility of the resin and the fiber

sizing as well an even application of the resin to the fiber under appropriate

processing conditions to avoid dry fibers.

Prepreg tape can be woven into broadgoods with various weaving patterns

appropriate to the application. The

choice of fiber type, resin, and fiber content may be adjusted to fit the

mechanical and cost constraints of the final part desired. Generally, in the case of polypropylene/glass

tape the percentage of fiber by weight can be set from 30 percent to 60 percent

without great difficulty.

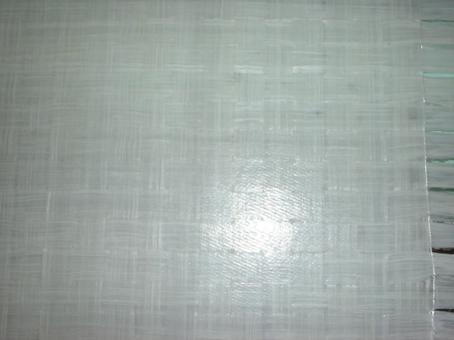

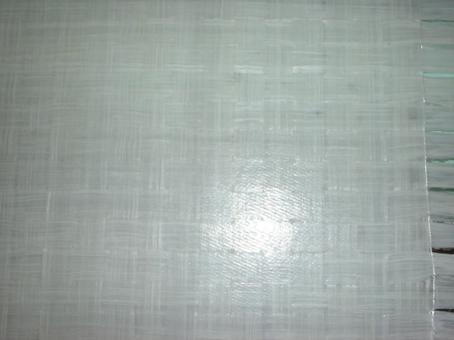

Polypropylene/E-glass tape was

produced in a 12.7 mm width and then woven in to a fabric as shown in Figure

2.2.1-1. This material is about 1 meter

wide. A close-up view is shown in Figure

2.2.2-2.

Figure

2.2.2-1 Roll of Woven

Polypropylene/E-Glass Fabric

Figure

2.2.2-2 Close-up View of Woven

Polypropylene/E-Glass Fabric

The woven fabric was consolidated

into a flat panel in a heated double belt press. This process formed the raw woven fabric into

a dense composite. A sheet of that

material is shown in Figure 2.2.2-3.

Figure

2.2.2-3 Consolidated Sheet of Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass

A close up of the same material

is shown in Figure 2.2.2-4. The

consolidated forms can be used as-is as structural panels, subsequently formed

in standard thermoforming operations, or joined to other components by fusion

or adhesive bonding.

Figure

2.2.2-4 Close-up of Consolidated Woven

Polypropylene/E-glass

The woven material can also be

consolidated by vacuum bagging and or bagged and autoclaved if additional

pressure is need to form the part. A

prototype bus floor subcomponent was fabricated from this woven form of

thermoplastic composite material using vacuum bagging methods with a one-sided

aluminum tool.

The particular materials incorporated

into the woven broadgoods were polypropylene (BP/Amoco 9965) and E-glass (Owens Corning 225-4588). The tapes were made using the Direct

Reinforcement Fabrication Technology (DRIFT) process and then woven into

broadgoods. Figures 2.2.2-5 and 2.2.2-6

show the weaving process that was performed by American Iwer, Greenville,

SC.

Figure 2.2.2-5 Loom Weaving

Thermoplastic Prepreg

Figure 2.2.2-6 Take-up

Accumulator for Woven Prepreg Fabric

Each layer of fabric when

consolidated is about 0.6mm thick. Flat

parts can be made in various thicknesses and widths using a heated double belt

press. Multiple layers of woven prepreg

may be consolidated into a single flat sheet using a belt press concept like

that shown schematically in Figure 2.2.2-7.

Figure

2.2.2-7 Schematic of Double Belt Press

A processing method that has some

similarity to the VARTM process is the vacuum bag thermoforming process. The tooling for vacuum bagging is

single-sided which reduces cost. The

tooling can be made from a variety of materials depending on the volume of

parts and the rate of production needed.

In addition, all of the bagging components and tooling need to

gracefully handle the process temperatures encountered with the resin system

utilized. Aluminum tooling has the

advantage of machinability and high thermal conductivity which can reduce both

heating and cooling time. Steel is the

most durable tooling, but also the most expensive. Regardless of the choice of tooling material,

one must size the heating and cooling function so that the respective heat and

cool cycles are acceptably rapid. For

most applications, direct electrical heating is the most inexpensive approach

to getting the tooling and prepreg up to processing temperature. Cooling can be effected with water spray into

internal channels of the mold that will turn of steam and be vented away

safely. It is also feasible to use

circulating oil as a heating and cooling medium which eliminates of the wiring

associated with the cartridge heaters.

Sizing of the heating capacity of the tooling is dependent on the mass

of the tool, the heat capacity of the tooling material, and how rapidly the

tool is required to heat up. The same

constraints hold for cooling capacity.

Figure 2.2.2-8 shows an example of an aluminum mold with associated

cartridge heaters. This particular mold

weighed about 320kg and could be raised to a temperature of 50˚ C in about

6 minutes. This required about 42kw of

heating.

Figure 2.2.2-8 Aluminum Mold

Half Showing Inserted Cartridge Heaters

Figure 2.2.2-9 shows mold

prepared for vacuum bagging of a woven thermoplastic material for the flooring

subcomponent. This prototype mold has

material hold-down clamps to keep the multiple prepreg layers initially

conformed to the mold for proper vacuum bagging to occur. In a production situation automatic slides

would perform the hold-down function to achieve a shorter cycle time.

Figure 2.2.2-9 Mold Prepared for

Vacuum Bag Thermoforming

Once a part is consolidated it

can be used as is or assembled to another component. In production circumstances vibrational or

ultrasonic bonding would be typical assembly tools. On a more limited prototype production hot

melt adhesives can be used effectively as shown in Figure 2.2.2-10. On a large part the adhesive can be applied

in the proper place and quantity and permitted to cool before the secondary

operation of putting the parts together and heating to bond, Figure

2.2.2-11.

Figure 2.2.2-10 Preparation for

Part Bonding with Low Melt Adhesive

Figure 2.2.2-11 Placement of

Secondary Part of Flooring Subcomponent to

be Adhesively Bonded

The design and testing of the

processed flooring subcomponent is described in Section 2.5.

2.2.3 Mechanical Testing Results

Several material combinations

were tested to confirm the impact and tensile properties of potential bus

components. In addition a study was

performed to investigate the possible influence of specimen width on the

measured ultimate tensile strength and modulus.

2.2.3.1 Tensile Data on Compression-Molded Panels- Effects of Test Sample Width

Tensile properties for

polypropylene/glass (PP/Glass) composites were reported previously based on

1-inch wide rectangular, tabbed specimens.

There has been some concern that the width of the specimen might

influence the measured tensile properties in long fiber thermoplastic

composites due to the cutting of fibers during specimen preparation. Therefore an experiment was performed in

which standard PP/Glass panels were tested using 12.7mm, 19.0mm, 25.4mm ,38.5mm

and 50.8mm wide samples to detect any trends.

The results of the studies are

illustrated in Figures 2.2.3.1-1 and 2.2.3.1-2 below.

Figure

2.2.3.1-1 Ultimate Tensile Strength as

a Function of Specimen Width and Orientation

Figure

2.2.3.1-2 Modulus as a Function of

Specimen Width and Orientation

The most obvious aspect of this data

set is that the samples taken transversely to main flow of the material

consistently shows reduced ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and modulus. This is the expected trend with the magnitude

of the difference between the longitudinal and transverse data depending upon

the anisotropy induced during molding.

In this particular case the modulus and UTS of the transverse specimens

are nominally 70 percent of the longitudinal values. The transverse specimens also have a

consistent pattern of being insensitive to the specimen width effect on modulus

or UTS.

Figure 2.2.3.1-1 and Figure

2.2.3.1-2 illustrates that there is no discernable correlation of modulus and

ultimate tensile strength to the specimen width. This supports the hypothesis that specimen

width does not effect mechanical property measurements with 25.4mm fibers using

compression molding as the process for fabricating the samples. This observation is important in that our

previous tensile data is not subject to reinterpretation regarding sample

geometry.

2.2.3.2 Polypropylene/Glass Impact Investigations-Gas

Gun, Falling Dart, And Izod Tests

Many composite materials used as

structural members are susceptible to Low Velocity Impact (LVI, less than 10m/s)

and Intermediate Velocity Blunt Object Impacts (IVBOI, greater than 10m/s and

less than 100m/s) such flying debris, stones/rocks and tool drops is a matter

of great concern and is not well understood; both in test methodology and

failure mechanisms. No standard test

methods presently address impact threats from such common phenomena. Traditional impact data for thermoplastics

relies upon notched-Izod impact, which does not correlate well to the common

impact threats.

In the present work the impact damage

resistance of extrusion-compression molded LFT - PP is studied for its damage

and energy absorption characteristics using an intermediate velocity gas-gun

(IVBOI) and low velocity drop tower (LVI) impactors. The compression-molded

panels were manufactured from LFT pellets.

This section reports results on

LVI and IVBOI pertaining to LFT glass/PP panels in which the damage response,

energy absorption characteristics and damage modes of the LFT panels are

investigated. Charpy and Izod type

impact test configurations are limited in terms of specimen size, impact

duration, and boundary conditions. A

more representative test would be the LVI and IVBOI scenarios.

The composite material considered

was comprised of BP-Amoco 10-9961 (PP) resin using glass fiber (Johns Mansville

840-BC-225) with an average fiber length in prepreg chips of 12.5mm, 60 weight

% fiber fraction, 2.5% 3200 polybond additive and 1% Schulman 3200 heat

stabilizer. LFT pellets were plasticized

and a charge (shot) extruded. The charge

was placed on a tool and compression molded to produce plaques. LFT plaques of size 10.16mm x 10.16mm were

cut for LVI testing and 21mm x 21mm for Blunt Object Impact (BOI). The average weight and standard deviation for

the BOI samples was 206.32g (Standard Deviation (S.D.)=

1.358g), 219.8g (S.D.= 1.822g), 225.27g (S.D.= 1.056g). The average areal density corresponded to

0.439g/cm2, 0.467g/cm2, and 0.479g/cm2. For LVI tests samples with areal density

0.439g/cm2 only were used.

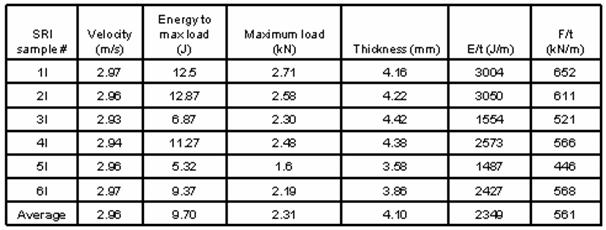

The LVI tests were conducted

using a Dynatup 8250 impact-testing machine equipped with a load cell of

capacity 1590kg. A hemispherical shaped

head tup of diameter 19.5mm and mass 0.12kg was used. The total dropped mass including the tup

mass, impactor and the holding bolts was 3.35kg for the hemispherical impactor. The samples were clamped using a pneumatic

assist mechanism, such that 76.2mm (3”) diameter of the sample face was exposed

to the impactor. The force-time,

energy-time and load-deflection response of the samples was measured using the

instrumented feature of the Dynatup instrument. The LVI tests were conducted on samples with

areal density 0.439g/cm-2. Damage initiation and progression was

monitored.

Figure 2.2.3.2-1 illustrates a typical

force-time-energy curve for the LFT glass/PP specimen. The energy absorbed and the peak force were

normalized with respect to the thickness (E/t and F/t respectively). The blue force-curve shows some noise on the

initial rise and is only one set of data.

Figure 2.2.3.2-1 Typical Force-Time-Energy Curve for

LVI of LFT Glass/PP Plate Red Curve is Energy and Blue Curve is Force

Table 2.2.3.2-1 provides the

details of eleven samples tested at an average impact velocity of 3 m/s, and

the resulting E/t and F/t values. The

average value of E/t was 3.54kJ/m and the F/t was 956kN/m. Impact failure was observed to be primarily

tensile fracture of the back surface. Figure 2.2.3-2a shows compression

indentation on the impact face, and Figure 2.2.3.2-2b shows the tensile side

fracture.

Table 2.2.3.2-1 Summary of

Falling Dart Impact Tests for Polypropylene/Glass

Figure 2.2.3.2-2

LVI to LFT Glass/PP Plate

(a)

Impact side and (b) Back (tensile) side

Note preferential cracking along

fiber orientation. The fiber orientation

is developed during the compression molding process accompanied by whitening of

the sample. The whitening, or crazing, was caused by straining of the

matrix. A combination of fiber pullout

and fiber breakage along preferential paths was observed, and shown in Figure

2.2.3.2-3a. The preferential orientation

of the fibers arises from the compression molding processing. Examples of fiber pullout bridging the cracks

are shown in Figure 2.2.3.2-3b. The long

fibers embedded in the matrix are seen to contribute to the energy absorption

though fiber pullout mechanisms.

Figure 2.2.3.2-3 LVI to LFT Glass/PP

Plate

(a) Fracture path

with bridging long fibers and (b) fiber pullout bridging crack

Intermediate Velocity Blunt

Object Impact test velocities ranging between 10m/s-100m/s were used to simulate

the effect of blunt objects such as rocks and debris traveling at highway

speeds. For this, a gas-gun was used to

propel a variety of projectiles over a velocity range of approximately 10m/s

to 100m/s. The gun consists of a

3m barrel, firing valve, and capture chamber, shown in Figure 2.2.3.2-4. Within the capture chamber, the specimen is

constrained, and the projectile velocity measurements are made. An aluminum sabot of 38.1mm diameter and a

mass of 100g was used as the blunt object projectile.

Figure 2.2.3.2-4 Gas Gun Test Apparatus

The capture chamber and velocity

data acquisition system is shown on the left and the gun assembly and pressure

transducer is shown on the right.

Two photoelectric chronographs

(Model–CED Millennium) were secured to the capture chamber with a transparent

optical window to record the incident and residual projectile velocity. The impact velocity is controlled by the

pressure of the working fluid, which in this case was nitrogen. A calibration curve was generated to

establish the relationship of the pressure to projectile velocity. The highest energy is absorbed at the

ballistic limit of the material, at which the projectile actually embeds in the

specimen.

Five samples were tested for each

test configuration in an attempt to accurately determine the critical (or

ballistic limit) velocity. Three test

configurations where considered, representing the effect of random and

preferential fiber orientations in addition to variations in areal density due

to processing. This is similar to the V50

ballistic limit, which is defined in terms of the projectile having a 50%

probability of completely penetrating the specimen at the critical

velocity. Two simply supported boundary

conditions on two and four sides with the supports 160mm apart were

considered.

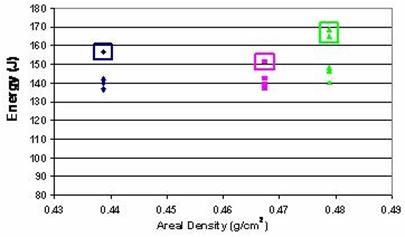

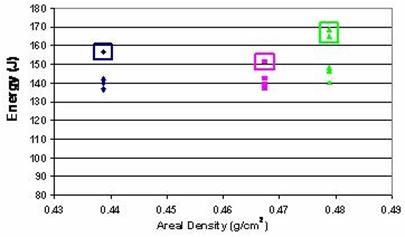

The results for energy vs. areal

density are shown in Figure 2.2.3.2-5.

Figure 2.2.3.2-5 Energy

Absorption vs. Areal Density for Three Samples

Data in Boxes from

Samples with some Fiber Orientation

For samples with areal density of

0.439g/cm2 and 0.467g/cm2, the impact response in terms

of energy absorption was of similar magnitude (approximately 142 J), while for

the 0.479g/cm2 the energy absorbed increased by about 8%. An increase in energy absorption with

increasing areal density is expected, however, the specimen with the areal

density of 0.479g/cm2 is also where the charge is placed during

processing. This results in a less

significant degree of fiber orientation thus less planes of preferred fiber

orientation, which is believed to contribute to the increased energy

absorption. Representative damages are

shown in Figures 2.2.3.2-6, 2.2.3.2-7, and 2.2.3.2-8.

Figure 2.2.3.2-6 Sample 020919-1-38b Showing IVBOI without Penetration

Kinetic Energy = 132.10J,

100g Sabot

Figure 2.2.3.2-7 Sample

020919-1-33b Showing IVBOI without Penetration

Kinetic Energy =

148.4J, 100g Sabot

Figure 2.2.3.2-8 Sample

020919-1-01b Showing IVBOI with Penetration

Kinetic Energy =

144.7J, 100g Sabot

The impact of a 100g projectile

was recorded using a high-speed camera with 14,000 pictures per second

providing 40ms

exposures. About 25mm maximum

deformation was observed in flexure combined with torsional oscillations of the

panel during the course of the impact deduced from the high-speed photography

tests with the specimen simply supported on two sides for viewing

purposes. For panels with normal

incidence (i.e., full contact of the projectile face with the sample) of

impact, the limiting damage occurred by punch-through (shear plug) near the

impactor where areas of high transverse shear stress exist. Away from the impactor, simultaneous tearing

across planes of preferential fiber orientation was the dominant failure

mode. In most of the tests, the edge of

the projectile made contact due to slight tilting of the projectile prior to

contact that resulted in an initial notch arising from the localized high

contact stresses which then proceeded to punch-through and tearing

failure. The onset of damage and

perforation are illustrated in Figures 2.2.3.2-9 and 2.2.3.2-10, respectively.

Figure 2.2.3.2-9 Sample

020919-1-65b

High-Speed Image of the

onset of Damage, Kinetic Energy=142.3J

Figure 2.2.3.2-10 Sample

020919-1-65b

High-Speed Image

Showing the Perforation of the Sample, Kinetic Energy=142.3J

The velocity for penetration of

the test panels varied from approximately 53m/s to 59m/s for the

100g sabot, and the maximum energy absorbed was approximately 169 J. Summaries of the IVBOI results are shown in Table

2.2.3.2-2.

Table

2.2.3.2-2 Intermediate Velocity Impact Tests on

Polypropylene/Glass Panels

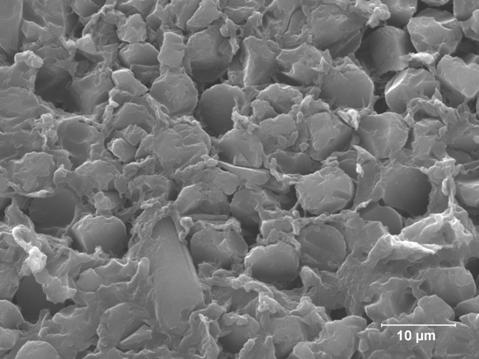

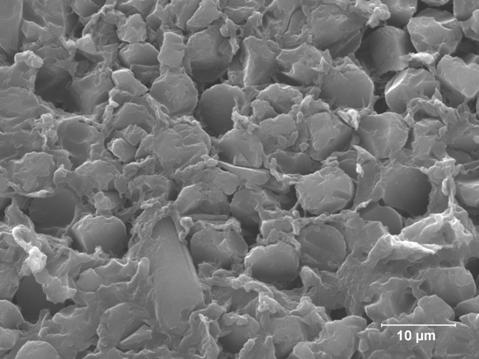

Representative fracture surfaces

of the impacted specimens were sectioned, mounted, and coated with

gold-palladium before viewing in a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). The images verified the initial assumption

that the fractures were occurring along planes of preferential fiber

orientation shown in Figures 2.2.3.2-11, 2.2.3.2-12, 2.2.3.2-13, and 2.2.3.2-14. In addition, a high degree of fiber pullout

can be seen along with matrix crazing.

The extent to which fiber fracture occurred prior to fiber pullout

cannot be determined because the fibers are discontinuous. Fiber fracture is believed to contribute a

large portion of the energy dissipation in ductile matrix composites undergoing

impact.

Figure 2.2.3.2-11 Sample 020919-1-34b Impacted with a 100g (38.1mm f)

Sabot at 53.1 m/s

The boxed region indicates the

fracture surface sample section. Energy

absorbed=142.0 J, specific fracture energy =142.9 kJ/m2.

Figure 2.2.3.2-12 SEM Normal to

the Fracture Surface of Sample 020919-1-34b Showing Fiber Pullout, Matrix Crazing

and Fiber Fracture

The preferential fiber

orientation is clearly visible.

Figure 2.2.3.2-13 SEM Normal to the Fracture Surface Showing Fiber Pullout,

Matrix Crazing and Fiber Fracture

The strong fiber/matrix adhesion

should be noted.

Figure 2.2.3.2-14 SEM Normal to the Fracture Surface of Sample

020919-1-39b after an IVBOI Test

The LFT glass/PP

panels exhibited localized damage by tensile-side fracture through a

combination of fiber pullout and breakage under LVI. In both the LVI and IVBOI testing, the

relatively flexible targets responded primarily by bending, which resulted in

high tensile stresses on the back face of the sample. The thickness-normalized value for absorbed

energy was determined to be 3.54kJ/m with peak load of 361kg. The long fibers bridged the crack faces, and

contributed effectively to energy absorption with LVI testing.

The LFT plaques simply supported on two sides

exhibited almost 25mm dynamic deflection and repeated torsional-flexural

vibrations of the panel during IVBOI, without visible damage up to areal

density and fiber orientation dependent threshold energy. For example, the threshold energy for the

samples with areal density of 0.439g/cm2 was 136 J. The failure mode was shear punch-through with

simultaneous tearing along planes of preferential fiber orientation with a much

larger fracture area than was seen in the LVI testing.

In both LVI and IVBOI, the matrix cracking

developed along preferential orientation of the fibers, which was developed

during the compression molding process.

Fiber pullout and breakage were dominant failure modes.

One set of low velocity impact

tests was performed on consolidated woven PP/glass, 60 percent fiber by

weight. The continuous fiber performed

well on impact tests as shown in Table 2.2.3.2-3. This is the same material used in fabrication

of the bus floor subcomponent described in later sections of this report. The impact characteristics are better than any

other PP/glass system that was tested during this effort. Only the polyurethane/glass combination (60

percent fiber by weight) provided a superior impact performance.

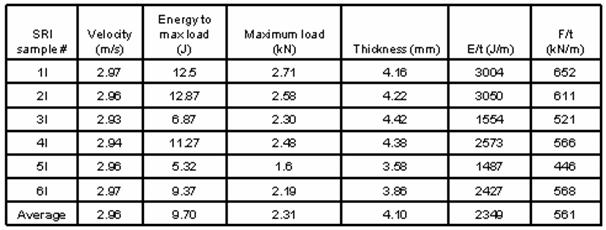

Table

2.2.3.2-3 Low Velocity Impact Tests on

Polypropylene/Glass Panels

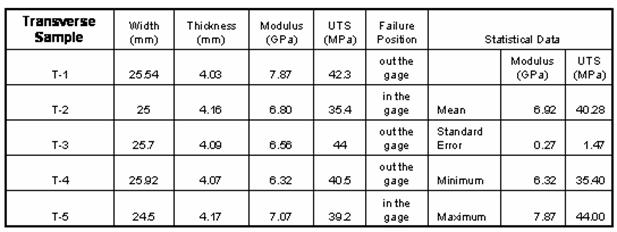

2.2.3.3 SMA/Glass Mechanical Test Results

SMA/glass test specimens were

made from unidirectional and random fiber panels. The unidirectional and random fiber panels

were tested for tensile properties and impacts tests were performed only on the

random fiber panels. The results are

summarized in Tables 2.2.3.3-1, 2.2.3.3-2, 2.2.3.3-3, and 2.2.3.3-4. The unidirectional fiber samples showed

properties superior to the longitudinal samples that were likewise superior to

the transverse fiber samples. This

confirms that anticipated fiber orientation effects of the longitudinal and

transverse fiber samples taken from random fiber panels. The results of the impact tests of the SMA

panels were inferior to the polypropylene/glass panels listed in Table 2.2.3.2-1.

Table 2.2.3.3-1

Unidirectional SMA/glass Fiber Tensile Properties

Table 2.2.3.3-2

Random Fiber SMA/glass Tensile Properties–Longitudinal

Orientation

Table 2.2.3.3-3

Random Fiber SMA/glass Tensile Properties–Transverse Orientation

Table 2.2.3.3-4

Low Velocity Impact Data– SMA Random Panels

2.2.3.4 Polyurethane/Glass Panel Impact Results

Polyurethane/glass thermoplastic

composite was investigated for application on parts requiring impact resistance

and finish. The polyurethane is

paintable as well as impact resistant.

The tabulation of several polyurethane forms including film is shown in

Table 2.2.3.4-1. The energy absorption

per thickness (E/T) is superior to any of the other materials that have been

tested in this effort. It is anticipated

that these materials may be useful for body panels and other parts subject to

impact damage.

Table 2.2.3.4-1

Polyurethane/Glass Panel Impact Results

2.4 Fire Safety of Flooring

The fire safety requirements

for interior mass transit applications are ASTM

E-162 and ASTM E-662. High composite fiber content promotes inherent flame

retardant characteristics, but additives and coating may enhance those characteristics. The composite fiber content of the fabricated

flooring subcomponents is 60 percent by weight, considerably higher than the 40

weight percent material used in the bus seat trials in last year’s

efforts. Therefore the good results

obtained last year with the 40 percent fiber material would be even better with

the current material formulation.

Nevertheless, additional investigation into improving the flame retardancy characteristics has continued. An overview of the principles governing the

function of fire retardants and previous data follow.

The function of a flame

retardant may be classified based upon the critical part of the combustion path

that contributes to flame spread.

Figures 2.2.4-1 and 2.2.4-2 (Marcel. M. Sommer, Evaluating the Results

of Research: Halogen-free Flame Retardancy to LFTs, Institut Fur

Verbundwerkstoffe; LFTs 2003; Brussels, Belgium;

May, 2003) respectively outline the critical process points and list the types

of flame retardants and their modes of operation.

Figure

2.2.4-1 Critical Points of Flame

Retardancy Function

Figure

2.2.4-2 Several Flame Retardants and

Respective Modes of Operation

Two different concepts have been

investigated. The first approach

requires compounding a flame retardant into the polymer matrix of the composite

and the second approach applies the flame retardant as a top coat during or

after manufacture of the component.

Looking on this approach, a non-halogenated flame

retardant was selected to eliminate the impact on smoke and toxicity reported

by halogenated materials. There are a very limited number of flame-retardants

available, especially for polypropylene. We tested the fire retardant Exolit AP751, made by Clariant, in a 40%

glass-reinforced polypropylene. The addition of the flame retardant changes the

impact behavior of the component. Adding 5% of Exolit AP751 reduces the Dynatup

impact performance by approximately 10%.

However, more important is the change in

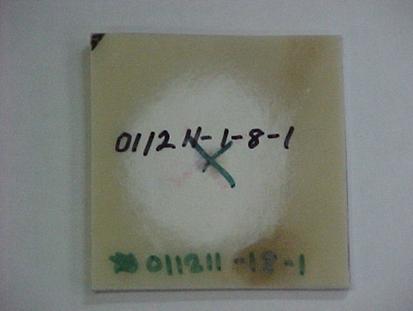

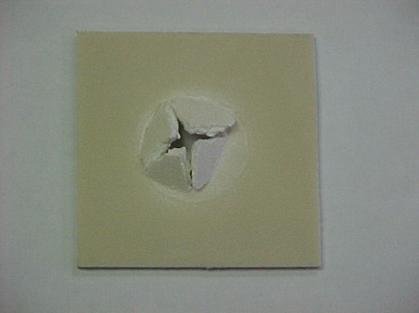

the type of failure. Figures 2.2.4-3 and 2.2.4-4 show a sample without and with,

respectively, flame retardant after Dynatup low velocity impact testing. The

sample with the flame retardant behaved as a brittle material.

Low velocity impact tests were used to evaluate damage

initiation, progression and fracture of the thermoplastic composite samples.

The equipment used to conduct the tests is an instrumented Instron 8250 drop

tower. The basic principle of operation is to drop a tup of known weight from a

set height onto the test sample. The maximum load and maximum energy absorbed

by the test sample and the damage to the sample is assessed.

Figure 2.2.4-3

Sample of 40 Weight Percent Glass Composite without Flame Retardant after Dynatup Impact

Testing

Figure

2.2.4-4 Sample of 40 Weight Percent Glass

Composite with Exolit AP751 after Dynatup Impact Testing

Two coating fire retardants were tested during our

previous work. Flame Seal FX-PL and

Thermaflex II-C from Avtec Industries are topcoat flame retardants rated as

UL-V0. These materials were applied by brush to polypropylene panels to gauge

the surface finish and flame retardancy.

These preliminary tests showed that both appeared to provide good flame

retardancy on 40 percent glass polypropylene composite. The Flame Seal product was selected on the

basis of surface finish after drying.

Panels were produced and coated with the Flame Seal FX-PL product. After curing at 60°C, the samples were

submitted to an independent testing lab for evaluations with respect to flame

spread and smoke density generation according to ASTM E 162-95 and E 662-95 respectively. The advantage of the coating method was that

mechanical impact performance would not be compromised by the fire retardant.

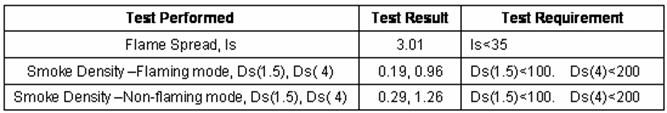

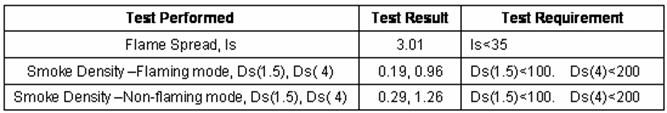

Results from an independent flammability-testing laboratory

were very favorable. The data in Table

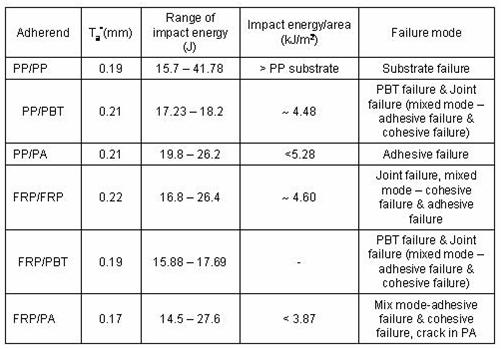

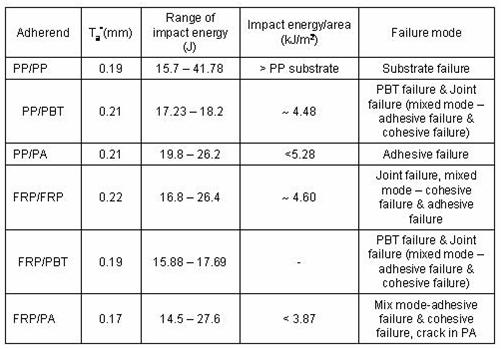

2.2.4-1 summarize the flame spread and smoke generation data and juxtaposes