|

BACKGROUND/PURPOSE

When the 121kmlong (75mile) Columbia River Highway between Troutdale

and The Danes was officially completed on June 27, 1922, it was hailed as

one of the engineering marvels of its age. The first paved highway in the

Northwestern United States, the Columbia River Highway was conceived,

designed, and constructed as both a scenic attraction and as a means of

facilitating economic development along the Columbia River corridor

between the Pacific Ocean and the areas to the east of the Cascade

Mountains. It was heralded as one of the greatest engineering feats of its

day, not only for its technological accomplishments but also for its

sensitivity to one of the most dramatic and diverse landscapes on the

North American Continent.

|

|

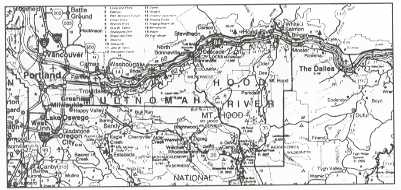

| Location site map |

The history of the development, decline, and continuing rebirth of the

Columbia River Highway is particularly instructive to the highway

engineering community as we approach the beginning of a new century and a

future of increasing reliance on the rehabilitation and restoration of

existing infrastructure instead of the construction of new highways. This

study also illustrates the manner in which state and local governments can

preserve and enhance existing highways that possess unique scenic and

historic qualities within the framework of modern design criteria. Much of

the discussion of the background and history of the highway has been

excerpted from the Historic Preservation League of Oregon's publication

Oregon Routes of ExplorationDiscover the Historic Columbia River

Highway' and A Traveler's Guide to the Historic Columbia River

Highway.'

Creation of the Columbia River Highway

Samuel C. Lancaster was the designer of the Columbia River Highway. His

romantic and deeply spiritual attitudes toward the environment and

mankind's relationship to nature framed subsequent discussions of the

Historic Columbia River Highway for all time. Looking back from the

vantage point of 80 years after its dedication, one cannot help but marvel

at how well Sam Lancaster accomplished his task. Highway building in the

United States was in its infancy. The automobile had not yet become the

dominant mode of transportation that it is today. The human foot, the

horse and wagon, the riverboat, and the railroads were the means of

popular transportation.

Travel conditions before the highway was built were grim. What roads

existed were crude and unstable dirt wagon trails. Pioneers trying to get

to the Willamette Valley from The Dalles during the early 1800's had

essentially three choices: (1) build a raft and risk the dangers of the

rapids near Cascade Locks, (2) pick their way along the Columbia River

Gorge, where they encountered mudflows, rockslides, canyons, and sheer

rock walls, or (3) follow the Barlow Trail over the southern flank of Mt.

Hood. Each of these routes was hazardous and slow. Oregon Routes of

Exploration Discover the Historic Columbia River Highway, Historic

Preservation League of Oregon, PO. Box 40053, Portland, OR 97240. `A

Traveler's Guide to the Historic Columbia River Highway, M&A Tour

Books, 3951 SE El Camino Drive, Gresham, OR 97080.

By the late 1800's, steamboats and railroads served some locations

along the Columbia Gorge, but a good road was needed for general traffic.

Early roadbuilding efforts, such as the Wagon Road from the Sandy River to

The Danes of the 1870's, were largely unsuccessful. Serious attention to

building a road through the Columbia Gorge grew with the advent of the

automobile. In 1908, Samuel C. Hill, often referred to as the "Father of

the Columbia River Highway" and a Good Roads Advocate in Washington and

Oregon, invited Sam Lancaster, already known for his pioneering

roadbuilding efforts in Tennessee, to the Pacific Northwest to share in

Hill's vision of creating a highway through the Columbia Gorge. In 1908,

Hill, Lancaster, and Major H.L. Bowlby (who was soon to become the Oregon

State Highway Department's first State Highway Engineer) traveled to

Europe to attend the First International Roads Conference. They traveled

extensively in Germany, Italy, and Switzerland to view and study European

roadbuilding techniques and designs.

|

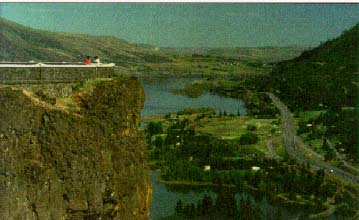

Typical overlook area along the

highway. |

|

|

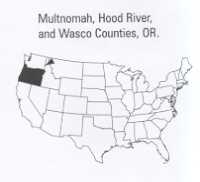

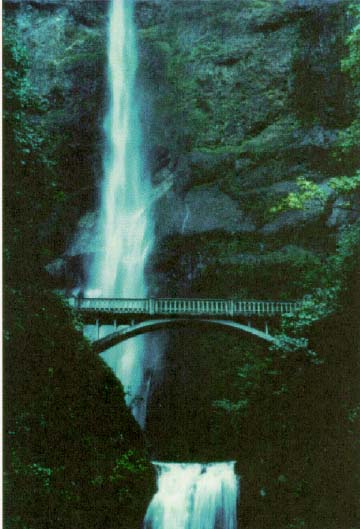

One of the many waterfalls along the route.

|

The Vision Becomes a Reality

Upon their return from Europe, Hill and Lancaster began designing and

building a prototype paved road system on the grounds of Hill's 28.3km

(7,000acre) estate at Maryhill, WA. In February 1913, the Oregon State

Legislature viewed the results of this effort and went away sufficiently

impressed to create the Oregon State Highway Department and Commission the

next month. Major H.L. Bowlby was subsequently appointed the first State

Highway Engineer; later Sam Lancaster was named Assistant State Highway

Engineer and Charles Purcell was named State Bridge Engineer.

On August 27, 1913, the Multnomah County Commissioners met

with Hill and the backers of the highway project at the Chanticleer Inn

overlooking the western end of the Gorge. The next day, Sam Lancaster,

attending as a guest of Hill's, was appointed Multnomah County Engineer

for the highway. (One year later the Columbia River Highway was designated

a State highway, setting the stage for future State involvement.)

Lancaster went to work immediately, beginning the survey and route

location from Chanticleer Point to Multnomah Falls in September 1913.

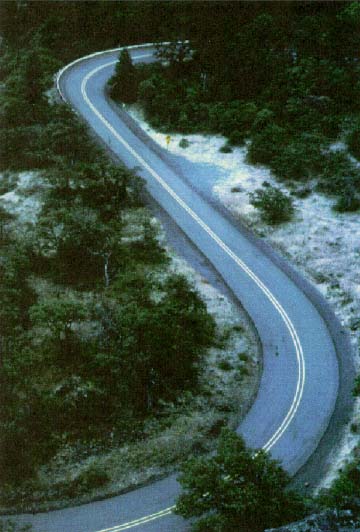

|

Typical curvilinear alinement |

|

From the very beginning, this was to be both a scenic and a modern

highway. The challenging requirements set by Lancaster were to locate the

road in such a way that it would be at least 7.3 m (24 ft) wide, have

grades no steeper than 5 percent, and have curve radii no less than 30.5 m

(100 ft). At the same time, the roadway was to be located so as to provide

maximum scenic opportunities, yet do as little damage to the natural

environment as possible. Amazingly, Lancaster was able to achieve all

these goals, even over the first segment of the highway, which required

accomplishing an elevation change of nearly 183 m (600 ft) in a distance

of less than 1.6 km (1 mile).

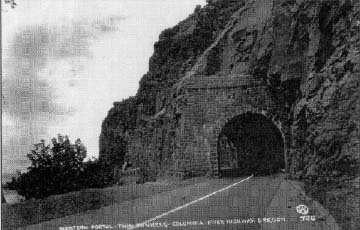

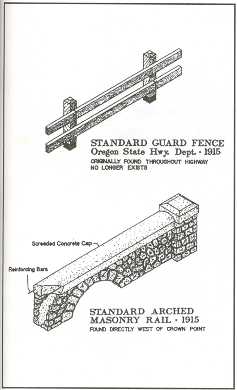

The construction of the highway incorporated a number of features then

found only in Europe such as miles of dry masonry walls (built by Italian

stone masons) and rock rubble guard walls with arched openings. At

Mitchell Point, John Elliott, the location engineer who worked with

Lancaster on the eastern segment of the highway, exceeded the achievements

of the legendary Axenstrasse around Lake Lucerne, Switzerland. Elliott

directed the construction of a tunnel bored through solid rock into which

were cut five openings instead of the three on the Axenstrasse, to allow

travelers to view the magnificent scenery. An original design element was

the construction of stone observation areas with benches for weary

travelers. Extensive use was made of the thennew construction material

reinforced concrete for bridges and viaducts, over the length of the

highway. Many of these structures are still in use today.

|

Early days of the Columbia River Highway.

|

|

The highway, although only partially paved, was officially opened on

July 6, 1915, between Portland and Hood River. Paving began in June 1915,

making the Columbia River Highway the first major paved road in the

Northwest. On June 7, 1916, the highway was officially dedicated with

ceremonies at Crown Point and Multnomah Falls. At 5:00 p.m. that day,

President Woodrow Wilson touched a button in the White House that

"electronically unfurled the flag of freedom to the breezes" at Crown

Point.

Construction continued eastward from Hood River along the alinement

established by John Elliot in 1915 to The Danes. This final section of the

highway included two tunnels bored through the bluffs near Mosier.

Finally, on June 27, 1922, Simon Benson, who was an ardent supporter and

benefactor of the project, ceremoniously spread pavement mixture on the

final segment at Rowena Point near The Dalles. After almost 9 years of

work on the Columbia River Gorge Highway, the final segment linking

Astoria to The Dalles was complete. From The Dalles to Troutdale, workers

had built an amazing 119 km (73.8 miles) of roadway, including 3 tunnels,

18 bridges (some of worldclass quality for their time), 7 viaducts, and 2

footbridges.

Early Economic Benefits of the Highway

The Columbia River Highway proved to be much more than just an

engineering marvel and a scenic attraction. It stimulated tremendous

economic growth in every community it touched. Restaurants served up

salmon and chicken dinners to hungry travelers. Automobile dealers and

service stations sprang up to fix tires and replenish fuel. Before long,

motor parks, auto camps, and the grand Columbia Gorge Hotel in Hood River

made it possible for travelers to experience a variety of overnight

accommodations. Retail stores flourished in the towns along the route, and

summer homes appeared on the forested slopes above the river and the

highway.

Decline and Disuse

Within a decade after its completion, technological advances in

transportation began to make the Columbia River Highway obsolete. Trucks

and cars became larger and faster, making travel on the narrow, winding

roadbed increasingly difficult and dangerous. By 1931, plans were underway

to make another road, but this one would be straighter and closer to river

level. Public enthusiasm for this replacement highway was tempered by a

lack of funds and, aside from a new tunnel constructed through Tooth Rock

near Bonneville Dam in 1935, little more was done. Nevertheless, interest

in the new highway remained high, and a portion of it was constructed from

Troutdale to Dodson in the summer of 1949.

By 1954, the new "waterlevel" freeway (originally designated as U.S.

Route 30 but now I84) finally reached The Dalles, but not without

significant damage to the original Columbia River Highway. Nearly 4.2 km

(26 miles) of the old road between Dodson and Hood River had been either

destroyed or abandoned. In 1966, the worldfamous Mitchell Tunnel was

dynamited to allow for the completion of the adjacent section of I84. Many

of the original bridges, stone guardrails, and observatories fell into

disrepair. Towns and businesses bypassed by the freeway suffered declines

as new economic opportunities were created at the freeway interchanges.

The only segments of the original route that remained usable were the

sections from Mosier to The Dalles and from Dodson to Troutdale. The

Historic Columbia River Highway began to deteriorate badly.

Renewal and Rebirth

Fortunately, the 1980's marked the reversal of this trend. Heightened

environmental awareness led to the creation of the Friends of the Gorge,

which spearheaded the successful effort to create the Columbia River Gorge

National Scenic Area. The preservation and interpretation of the historic

highway is specifically mandated in the Federal enabling legislation,

which also created the Bistate Columbia River Gorge Commission.

A parallel historic preservation movement led to a survey and inventory

of the historic highway by the National Park Service. In 1983, the Oregon

DOT successfully nominated the surviving sections of the Historic Columbia

River Highway to the National Register of Historic Places. The Historic

Preservation League of Oregon led the successful effort to create the

Historic Columbia River Highway Advisory Committee to monitor changes,

alterations, and improvements to the highway.

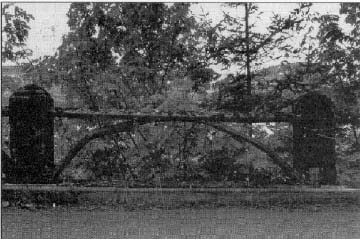

|

Early days of the Columbia River

Highway. |

|

|

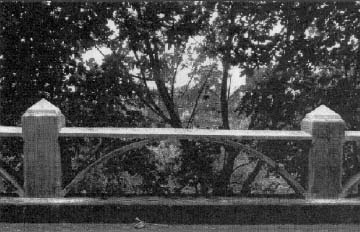

After restoration. |

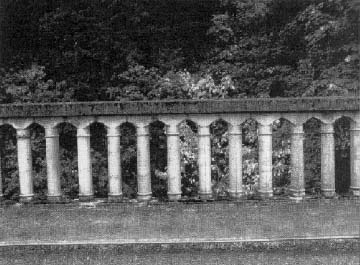

Signs of the rebirth of the great road are everywhere. The Oregon DOT

is doing an excellent job of rebuilding stone guardrails and concrete

caps, recasting and installing delicate concrete arches along the

viaducts, and signing the highway with an appropriate logo. The Highway

Division of the Oregon DOT is also in the process of developing a longterm

master plan for the restoration and reuse of the highway. The Friends of

Vista House, in cooperation with the Oregon State Parks and Recreation

Department, have restored the Vista House as an interpretive center.

Today, millions of visitors each year drive, hike, and bicycle along

portions of the highway.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND DESIGN ISSUES

AND CONSTRAINTS

|

Perhaps the single most distinguishing feature of the ongoing

efforts to rehabilitate the Historic Columbia River Highway is that

the designs are intended to replicate the original configuration of

the facility as it existed at the time of its completion in 1922.

This is analogous to the historic preservation process applied to

buildings to return them to their original conditions. Current

Oregon DOT plans call for the restoration of as much as possible of

the entire 119 km (74 miles) from Troutdale to The Dalles as either

a scenic highway or a hiker/biker trail.

The location of the highway in a National Scenic Area prevents

the construction of any projects that would have an adverse impact

on the defined historic resource, which in this instance is the

highway itself. |

|

ACTIONS TAKEN TO RESOLVE ISSUES

CrashTested Historic Guardrails

One of the more impressive ongoing restoration projects involves the

replacement of existing steel guardrails installed over the past several

decades with a "new" crashtested twobeam timber guardrail backed by wood

and steel that closely replicates the original 1915vintage guardrail

design, of which no sections remain today. The "new" guardrail has been

crash tested at 80 kph (50 mph) and approved for use by the FHWA

nationwide. Interestingly, evidence in the archives of the Oregon DOT

indicates that the original 1915 guardrail design was adopted by the U.S.

Bureau of Public Roads and several States in the 1920's and 1930's as the

"standard" guardrail for use in similar rural environments.

Oregon DOT staff noted that, if current AASHTO guidelines were to be

fully adhered to, the historically accurate replacement guardrail would

need to be installed at many more locations than where it previously

existed and it is currently being reinstalled.

Hiker/Biker Multiuse Design Elements

In places where it would not be economically feasible to recreate the

historic road in its original location, a representative hiker/biker trail

is planned for construction. In such areas as the nowclosed Mosier

Tunnels, which are too narrow to accommodate two travel lanes wide enough

for modern vehicles, the rubblefilled tunnels will be rehabilitated to

their original conditions and will provide access limited to bicycles and

pedestrians. Wherever possible, the "new" sections of facility needed to

accommodate the current "missing links" in the original 1920's vintage

alignment will utilize the same historical design criteria of maximum 5

percent grades and 30.5mminimum (100ft) radius curves, although a slightly

narrower pavement width may have to be provided in certain locations. The

new hiker/biker trails are being designed in accordance with current ADA

provisions in order to allow use of these facilities by individuals with

disabilities.

|

Newly installed steelbacked wooden guardrail.

|

|

Aesthetic Considerations of Enhancement Projects

|

Throughout the design of the current enhancement/rehabilitation

projects, Oregon DOT staff members have been particularly cognizant

of the need to consider the aesthetic qualities of the Columbia

River Gorge. An example of this concern is the manner in which the

remediation of a continuing rock fall area was addressed as part of

the rehabilitation project encompassing Tanners Creek to Eagle

Creek. Because it was not possible to use Oregon DOT's standard

steelcolumnsupported, metal rockfall fencing, the decision was made

to shift the roadway alignment slightly to provide a greater

separation between the rock face and the edge of the travelway. The

resulting lateral separation space is able to accommodate falling

rocks.

Moreover, because virtually the entire length of the Historic

Columbia River Highway is on the National Register of Historic

Places and the highway is located in a designated National Scenic

Area, no roadway widenings are permitted. The result is that the

"new" roadways are identical in cross section to the existing

highway.

In the Tanners Creek area, the planned improvements will involve

the removal and relocation of existing overhead electrical utility

lines and poles and the removal of some trees to reopen some of the

historic vistas of the gorge. One issue to be addressed here is

determining exactly which of the trees should be removed.

|

Cost Considerations of Historic Enhancement Projects

The costs of the ongoing rehabilitation and enhancement projects for

the Historic Columbia River Highway are considerable. For example, the

initial installation of 886 m (2,906 linear ft) of tworail steelbacked

timber guardrail had a total bid price of $119,146 or about $41.00 per

linear ft ($134.50 / m). If standard Oregon DOT steel guardrail had been

installed, the estimated cost would have been approximately $32,000 or

about $11.00/linear ft ($36.09/m). The historically accurate timber

guardrail costs about 31/2 times as much to install as traditional steel

guardrail. Since the installation of the initial sections of the tworail

steelbacked timber guardrail in 1992, however, no maintenance of the

guardrail has been necessary. It is anticipated that the guardrail will

eventually need to be repainted about once every 5 years. The estimated

cost of this activity (in 1994 dollars) is approximately $3.20/linear ft

($10.50/m).

Similarly, the requirement for the use of hand labor in association

with the reconstruction of stone guard walls has resulted in substantially

higher costs for this activity than if standard steel guardrails or

concrete barrier walls had been installed. However, the Oregon DOT

understands the need for an appropriate balance to be maintained between

enhancement, maintenance, rehabilitation, and new construction projects

and remains committed to the Historic Columbia River Highway projects.

LESSONS LEARNED

The experience of the Oregon DOT with the design and construction of

improvements to the Historic Columbia River Highway has the potential for

widespread application across much of the United States. In particular,

many of the generally lowvolume rural highways that have been, or are

proposed to be, designated as "scenic highways" date from the general era

of the original Columbia River Highway and thus share similar geometric

constraints. Now that regional through traffic that once used these older

highways has shifted to more modern parallel freeway routes, opportunities

may exist for the enhancement and rehabilitation of these older routes to

a configuration similar to that at the time of their original

construction.

The existence of an FHWAapproved tworail steelbacked timber guardrail

that has been crash tested to 80 kph (50 mph) provides an alternative to

the use of current steel guardrail designs, especially on those routes

where the timber guardrail would help to provide a more aesthetically

pleasing vista. Finally, the experience of the Oregon DOT with the

construction and maintenance of such "nontraditional" roadway design

features as timber guardrails and stone guard walls should prove to be of

use to a number of other States facing similar requests from historic

preservation groups.

|

Young's Creek (Shepards Dell) Bridge after

restoration. |

|

Spindle railing after restoration on the Young's

Creek Bridge. |

|

|

HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY

AT A

GLANCE |

| Setting: |

World-class designated National Scenic Area; rural highway

passing through small communities. |

| Length: |

Approximately 119 km (74 miles) (from Troutdale to

The

Dalles) |

| Traffic Volume: |

Widely variable, from approximately 4,200 vehicles per day

in most heavily traveled western sections (with peak summer

weekend volumes of approximately 7 ,500 vehicles per day) to

about 500 vehicles per day in the most lightly traveled

eastern sections |

| Design Speed: |

Not applicable; rehabilitation of existing historic

roadway; esti mated design speed of 56 to 73 kph (35 to 45

mph) |

| Type of Road: |

Historic, scenic highway (owned and maintained by Oregon

DOT); functional classification -collector |

| Design Cost: |

Current enhancement/rehabilitation projects only-

Not

available (in-house by Oregon DOT staff) |

| Construction Costs: |

Current enhancement/rehabilitation projects

only-

$120,000 for initial installation of 886 m (2,906

linear ft) two-rail steel-backed timber guardrail; $35,000 for

initial rock guard wall reconstruction; other projects

totaling approximately $4.0 million are planned for the next 3

to 5 years |

| Key Design Features:

|

Restoration/rehabilitation of existing historic highway to

original condition at time of completion in 1922; installation

of two-rail steel-backed timber guardrail very similar in

design to original; reconstruction of rock guard walls;

reconstruction of original concrete bridges |

| Debits: |

Design limits operating speeds to 48 to 65 kph (30 to 40

mph) in most areas |

| Similar Projects: |

Paris-lexington Road, KY

Oyster River Bridge, Durham,

NH

SR 89, Emerald Bay, lake Tahoe, CA

SR 92, lebanon

Road, New Castle County, DE |

Contacts for Additional

Information: |

Ms. Jeannette Kloos

Scenic Area Coordinator

Region

I

Oregon Department of Transportation

123 NW

Flanders

Portland, OR 97209-4037

Tel:

503-731-8234

Fax: 503-731-8259

Mr. Dwight A. Smith

Cultural Resource

Specialist

Technical Services Branch

Oregon Department

of Transportation

1158 Chemeketa Street, N.E.

Salem, OR

97310

Tel: 503-986-3518

Fax:

503-986-3524 | | |