|

<< Chapter 6

|

Home |

Chapter 8 >>

|

This chapter provides descriptive case studies of the four HOT lane facilities currently operating in the United States, as well as two recent HOT lane initiatives. Presented in a parallel format, the cases illustrate the variety that abounds in the nation’s HOT experience, as well as many common themes.

The cases have been assembled through review of project documentation and interviews with associated state, county and local officials, as well as with consultants and private concession companies. While they present different points of view and offer observations on how and why various occurrences came to pass, the cases are intended to be journalistic and non-judgmental. Most importantly, they offer real-life illustrations of the different policy and technical issues addressed in the earlier chapters of this document.

Background

Houston’s IH 10 Corridor, known commonly as the Katy Freeway, extends 40 miles from the Central Business District of Houston west to the Brazos River (Figure 24). It was constructed from 1960 to 1968 to replace the old Katy Road, when Houston was a much smaller city. Since its construction, explosive growth in private residences, corporate offices, and retail centers along the route have made the IH-10 corridor a central artery of western Houston.

Designed to carry 79,200 vehicles per day, the Katy Freeway now carries over 207,000 vehicles per day, and it is considered one of the most congested stretches of freeway in Texas. The Katy also has the highest daily truck volumes of any roadway in the state. Traffic generated from six radial highways, nine employment centers, the Port of Houston, and through truck traffic are all compressed into three lanes in each direction. Congestion may be present for 11 hours or more each day, extending well beyond conventional peak hours, and there is even congestion for long periods during the weekends. Some estimates place the cost of the Katy’s traffic delays to commuters, residents and businesses at $85 million a year.

As currently configured, the Katy Freeway has three main lanes (or general purpose lanes) and two frontage-road lanes for most of its length in each direction. Situated in the center of the freeway is a barrier-separated high-occupancy-vehicle/toll (HOT) lane for carpools and buses, making for a total of 11 through lanes. A single reversible lane, the HOT facility handles inbound traffic in the morning and outbound traffic in the evening. The HOT lane, which runs for 13 miles from west of State Highway 6 to west of Washington Avenue, has been in operation since 1998, when it was converted from the freeway’s original high occupancy vehicle lane dating from 1988. Although the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) owns and operates the Katy Freeway, the center QuickRide lane is operated by the Harris County Metropolitan Transit Authority (Houston Metro), which operates all HOV lanes in the region. This arrangement adds some institutional complexity to the HOT facility.

For a number of reasons, the Katy Freeway makes for a rich study of HOT lane implementation. First, the QuickRide system offers an example of a regular HOV lane converted to a tolled high-occupancy facility, as well as of HOT lane operation. Additionally, current planning by TxDOT and other Houston transportation agencies for a major reconstruction of the Katy Freeway may bring a dramatic expansion of the center HOT lane. The various agencies involved in the Katy and the alternatives under consideration for its expansion provide a window into some complex dimensions of HOT lane planning. Finally, the success of the Katy HOT lanes encouraged Houston Metro to expand the QuickRide system in November 2000 to another well traveled corridor in the region, the Northwest Freeway or US 290.

HOV Beginnings and Conversion

Since the 1980s, escalating travel demand on the I-10 West in Houston has pushed transportation planners and engineers continually to find new solutions to accommodate growing traffic. In 1984, TxDOT and Houston Metro opened an HOV lane on the Katy Freeway. As a joint project of Houston Metro and the State Department of Highways and Public Transportation, the Katy HOV lane was constructed with support from Federal Transit Administration (FTA) funds. Its operation was initially dedicated for transit. Although it now operates as a high occupancy toll lane under Houston Metro’s QuickRide, the lane’s physical form has not changed. Today, two plus-occupant vehicles may pay to use the reversible one-lane facility during hours when three-plus requirements are in effect. Concrete barriers separate the 13-mile QuickRide lane from three outer general purpose lanes in each direction, and there are three intermediate access points.

When the Katy HOV lane first began operating, eligibility requirements were at their most restrictive. Initially, only buses and authorized vanpools were allowed to use the lane. The resultant under-utilization gradually encouraged a loosening of the HOV entry rules, and slowly, registered carpools of four or more, then three or more, then two or more were allowed into the lane. As restrictions were relaxed, traffic on the facility grew, and more restrictive carpool rules were eventually reinstated at certain hours of the commute to reduce traffic on the facility. When congestion in the lane under two-plus HOV operation began to defeat the lane’s travel time advantage, the three-plus carpool restriction was reinstated.

With two-person carpools no longer allowed, the number of persons moved by the lane during the peak hour declined 30 percent. Attempting to increase the number of people moved by the HOV lane while also preserving the facility’s time advantage, Houston Metro and TxDOT launched a value pricing pilot on the existing 13-mile HOV-lane in January of 1998.

The QuickRide program, initially funded as an FHWA Priority Corridor Program and designated as a value pricing pilot, converted the Katy Freeway HOV-lane to a high-occupancy toll lane that uses price and occupancy requirements to manage traffic service in the lane.

The QuickRide System

Under the QuickRide system, still in operation by Houston Metro in 2002, buses and three-plus carpools continue to use the Katy HOT lane free of charge at all times, and single-occupant vehicles continue to be prohibited from the lane. Two-plus carpools may use the lane without charge during the morning and evening rush hours, except during its greatest peaks–from 6:45 AM to 8 AM and from 5 PM to 6 PM Monday through Friday. During these times, when demand for the facility is greatest, two-person carpools may use the lane for a $2.00 toll; only three-plus carpools use the lane for free.

The exclusion of single-occupant vehicles from the lane makes the Katy QuickRide one of two HOT-lane facilities in the U.S. that does not allow single-occupant users if they are willing to pay a toll. The other is Houston’s Northwest Freeway, also part of the QuickRide system. When operated as a regular HOV lane, the Katy lane was at near-gridlock. The decision by QuickRide operators to disallow single occupant drivers to use the lane—even if willing to pay the toll—reflected the corridor’s high travel demand and its limited capacity (one reversible lane), as well as SOV use restrictions tied to the HOV lane’s original construction financing from the FTA. The admission of single-occupant vehicles (SOV) to QuickRide would quickly congest the facility, unless the fee for SOVs were high enough to deter most from using the lane. Operators expected that the number of two-plus carpools that would take advantage of the buy-in opportunity would still allow the lane to operate at free flow.

QuickRide Operations

Since its inception on the Katy, the QuickRide system has used fully-automated toll collection. In fact, the Federal Priority Corridor earmark used for the project was designed specifically to fund ITS applications. Original project plans for the Katy included the use of revenue collection technology in the corridor.

Windshield-mounted electronic transponders are issued by Houston Metro, and transponders issued by the Harris County Toll Road Authority (HCRTA) are also accepted at the facility, provided users enroll in the QuickRide program and submit the transponder ID number. The QuickRide application form outlines the facility’s operating procedures, applicable fees, required equipment, monthly billing statements, violations and penalties, and conditions for termination of service.

Large digital displays at approaches to the QuickRide lane inform drivers when QuickRide rules are in effect, and overhead readers deduct the toll from the user’s prepaid account. An initial balance of $40 is required on each transponder. When the account balance falls below $10, the user’s credit card is charged to bring the balance back to $40. Monthly statements reflect all trip costs and credit card charges. In its first year operating QuickRide, Houston Metro limited to 600 the number of transponders issued to use the facility. As of April 2002, it had issued over 1,500 transponders for QuickRide access on both the Katy Freeway and the Northwest Freeway QuickRide lanes. The initial cap on transponders allowed facility operators to regulate the limited spare capacity on the HOV lane

QuickRide Public Outreach

Before launching the QuickRide program, Houston Metro and TxDOT, along with a private consultant, conducted a number of focus groups to assess public sentiment toward the proposed fee system. Additionally, the public information staffs of both agencies identified issues that would be important to address when crafting marketing and public information materials for launching the QuickRide program.

Rather than create a separate administrative entity for the QuickRide system, the project sponsors chose to direct potential users to the Metro carpool matching service. In program brochures and on the QuickRide website, potential customers are instructed to call the METRO RideShare Information Line for an application.

In late December 1997, public advertisements for the QuickRide program began to appear in print and radio media outlets. Outreach efforts also included distributing press releases and direct mailing brochures and applications to households in targeted zip codes.

The QuickRide webpage has been another source of information for the public. (See http://www.hou-metro.harris.tx.us/services/quickride.asp.) The site is simple in comparison to webpages for the privately owned SR-91 and publicly operated I-15, but it provides necessary information about the facility and its operations. By contrast, the SR-91 website allows potential users to apply for an account online, and offers current users the ability to manage existing transponder accounts online. The I-15 website provides a downloadable application form for its FasTrak program. Applicants to the QuickRide program may download an application from the QuickRide webpage or may call the Metro RideShare to request one.

In fall 2000, Houston Metro launched QuickRide operations on a second HOV facility in Houston: the Northwest Freeway, or US 290, which connects the northwest suburbs of Houston with downtown, feeding into the 610 loop. Like the Katy, the Northwest Freeway has hosted an HOV lane for over a decade. As demand for the facility grew rapidly in the late 1990s, Houston Metro studied the possibility of increasing the occupancy requirements on the facility and introducing QuickRide operations. These changes were implemented gradually in 2000, making the Northwest Freeway Houston’s second HOT facility.

In 1990, Houston Metro opened an HOV on the Northwest Freeway. The Northwest lane runs for 13.5-miles and has operated as a one-lane barrier-separated reversible HOV lane since its inception. Under HOV operations, travel in the Northwest HOV lane was permitted only for transit, school and private buses, taxis, vanpools and two-plus carpools during the peak morning and evening periods. The lane’s design encourages transit use, as most of its access points are through transit stations or park-and-ride lots. Through the 1990s, lane use expanded, and by 1998, the facility served 6,400 vehicles and 16,200 passengers daily. From September 1997 to April 1999, the lane witnessed a 37% increase in the number of peak hour vehicles. This rapid increase, particularly during the AM peak, caused operations to deteriorate. Average speeds in the Northwest HOV-lane slowed to between 20 and 30 mph in the AM peak and the level-of-service sunk to “F.”

Crowded HOV conditions also impacted buses and bus passengers using the facility. Buses serving the Northwest’s park-and-ride facilities experienced on average 15-minutes of delay as well as increased operating expenses. Additionally, the large number of cars exiting the HOV facility at its terminus at the Northwest Transit Center negatively impacted the efficiency of bus movements and bus transfers that take place there. Commuters who arrive at park-and-rides along the facility and use buses on the Northwest HOV lane to reach downtown were particularly distressed. Commuter complaints to Metro noted deteriorating operations, delays, reliability problems, and lateness.

As Houston Metro considered how to address the situation, the successful three-plus HOV operation on the Katy stood out as a possible solution. Before and after studies of the Katy showed that its HOT lane application had the following positive results:

Metro engineers concluded that implementation of three-plus carpool requirements would restore travel time benefits on the Northwest HOV-lane during the AM peak, when crowding was most problematic. The step was viewed as necessary if Metro was to maintain its policy of operating HOV-lanes at 50 mph or above. TxDOT approved the proposal, and in early 2000, Metro changed occupancy requirements on the Northwest HOV from two-plus to three-plus carpools only during the morning rush. The facility experienced a noticeable drop in usage, alleviating crowding and restoring levels of service for transit users.

In November 2000, high occupancy toll operations were launched on the Northwest Freeway. While three-plus operations in the AM peak had relieved the significant congestion problems, there was now some spare capacity on the lane. As with the Katy HOT lane, the extra capacity was opened to paying two-plus carpools, and it continues to operate on this basis. QuickRide allows paying two-plus carpools to use the lane only in the morning peak when three-plus occupancy requirements are in effect. From 6:45AM to 8:00AM, when the facility serves inbound traffic, three-plus occupant vehicle may use the lane for free, but two-plus vehicles must pay $2.00 to use the lane. Single-occupant vehicles are never allowed on the Northwest’s QuickRide lane, making its occupancy strategy identical to the Katy’s. QuickRide transponders are accepted at both the Katy and Northwest high occupancy toll facilities. As of April 2002, over 1,500 transponders were in circulation for use on the two facilities, and an average of 160 users traversed the two facilities each day.

The QuickRide Program in place on the Katy Freeway and the Northwest Freeway offers a notable example of HOV operations expanded to incorporate HOT lane use. Moreover, the Katy and Northwest HOT lanes are unique for prohibiting the entry of single-occupant vehicles, even on a fee per trip basis. While the evolution of the QuickRide system is a useful case study in itself, the number of paying users that these two facilities could accommodate is limited. Expansion plans for the Katy Freeway are currently under consideration and could significantly increase the scale and scope of HOT lane operations in the Katy Corridor. As they currently evolve, these plans also provide insight into some aspects of HOT lane planning and implementation.

Expansion Plans for the Katy Freeway

In 1995, TxDOT initiated a Major Investment Study (MIS) of the Katy Freeway corridor. Following federal requirements for major transportation investments, the MIS was intended to identify present and future mobility needs in the corridor, evaluate alternatives for transportation improvements and investments, and assess local environmental and community concerns. The study identified seven alternatives that could be pursued to improve the freeway, ranging from a no-build option to the addition of fixed-guideway transit with improved transit access and feeder routes. The MIS process then examined each alternative for engineering feasibility, transportation impacts, environmental consequences and financial feasibility, and ultimately presented a locally preferred alternative.

The preferred alternative would add one HOV-lane from downtown Houston to IH-610 and from SH-6 to Katy, and would have two special use or managed lanes in each direction between IH-610 and SH-6, one general purpose lane in each direction between IH-610 and Katy, and auxiliary lanes and frontage roads at major intersections. This scheme would expand the Katy’s current 11 lanes to 18 lanes, with a total of four general use lanes in each direction, two managed lanes (without defining what type of managed lane) in each direction, and three lanes on frontage roads in each direction. In 1995, TxDOT estimated the plan would cost roughly $1.1 billion, and revenue from the special use lanes would total $225 million over 25 years. Construction would begin in 2003 and continue for 10 years, and a combination of Federal and State funds gathered primarily from fuel taxes would finance the construction.

One aspect of the TxDOT proposal that is of particular interest to HOT lane planning is the fact that the operation of the four managed lanes is left unspecified. In fact, according to TxDOT, the managed lane/special use concept was used as a placeholder when developing the preferred alternative, and the TxDOT has contracted with the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) to study alternative operational strategies for those lanes. They could, for instance, be used as dedicated truck lanes or as toll lanes.

After the MIS results and a follow up environmental impact study (EIS) were sent to the FHWA for a record of decision, planning for the Katy Freeway corridor took an unexpected turn. In March 2001, the Harris County Toll Road Authority (HCTRA) proposed to assume responsibility for the four managed lanes and to construct them as a regular toll road. HCTRA’s offer would create a HCTRA sponsored tollway in the Katy Freeway median, and add to the two toll facilities in Harris County already operated by the authority.

As the traditional toll road operator in the area, HCTRA viewed the planned Katy expansion as an opportunity to add a facility to its operations. The authority would operate the two managed lanes in each direction as toll lanes. HCTRA also offered to provide $250 million in revenue bonds backed by toll revenue from its existing facilities to finance construction of the Katy special use lanes. HCTRA also offered TxDOT another $250 million as a loan to be paid back over 10 years; this loan would free other TxDOT funds for spending on other projects in the Houston District.

Federal review is needed on two counts for the HCTRA plan: (1) for the environmental impacts and (2) for the proposed tolling strategy. First, a supplemental EIS may be required for the HCTRA plan. Although the FHWA had issued a favorable record of decision in February 2002 on the Katy EIS, HCTRA’s proposal to build and operate the four center lanes as a tollway was announced after the EIS was submitted to federal authorities. If the potential environmental impacts of HCTRA’s operating plan for the four lanes differ significantly from those outlined in the original EIS, FHWA may require a supplemental EIS. This could lengthen the environmental review process and could alter the consensus crafted on the original expansion plan. As of June 2002, FHWA was determining whether a supplemental EIS was needed. Second, the FHWA will have to approve tolling on the expanded facility—not just for two-plus carpools, but for single occupant vehicles as well. As discussed below, TxDOT and HCTRA have sought approval for the plan through the Value Pricing Pilot Program.

Public Outreach

Most institutional representatives interviewed for this case study report that a broad consensus favors reconstruction of the freeway. The corridor’s extreme congestion and poor road conditions have helped to build support for reconstruction, and the public outreach process followed during the major investment study also worked to identify a solution with broad public support.

Aiming to provide public input and oversight into the study, the MIS process involved years of discussion, planning, and public meetings with businesses, community members and elected officials. A formal Steering Committee for the study included representatives from TxDOT, the City of Houston, the Houston-Galveston Area Council, FTA and FHWA, Houston METRO (the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County), and the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission. A Conceptual Advisory Group facilitated input from other neighboring political jurisdictions, business associations, and community groups.

During the study period, a total of 14 public meetings were held and nearly 1400 individuals participated. Public concerns raised during the study addressed operational issues on the existing HOV-lane, including concerns about the limited access points to the QuickRide lane and its limited ability to serve more drivers or to accommodate increasingly two-way travel. Some expressed the need for greater connectivity between the Katy and other HOV facilities.

Local elected officials, including Congressional representatives, the County Judge, and the area’s representative to the three-seat Texas Transportation Commission, have largely voiced approval of the expansion plan. Officials have emphasized the financial advantages to using HCTRA funds to construct toll lanes on the Katy. The public has not had a chance to formally comment on the toll proposal.

Institutional Issues

The number of public agencies with an interest in the Katy Freeway makes for complex institutional considerations in planning for HOT lanes in the corridor. Although the Katy Freeway itself is owned and operated by TxDOT, FTA funds were used to construct its median HOV lane, reserving the lane for transit and carpools. Moreover, since its inception, the center HOV lane has been operated by the Houston Metro, a transit agency, under a cooperative agreement between Metro and TxDOT known as the Transitways Master Operations and Maintenance Agreement. When Metro has contemplated changing occupancy requirements or levying tolls for two-plus users on the Katy (or on the Northwest Freeway HOV for that matter), TxDOT has had to approve the measure. Additionally, under the Katy’s current configuration, Metro cannot allow SOVs on the QuickRide facility because the FTA’s original investment in the lane.

Given current proposals for the Katy’s reconstruction and expansion, the future of HOT lanes on the freeway involves additional institutional considerations. For one, HCTRA’s offer of $250 million to finance construction and to operate Katy toll lanes has considerable appeal to local authorities. Financing from HCTRA would allow the project to be built sooner and would free funding formerly designated for the Katy for use on other projects in the region.

Second, because HCTRA’s proposal would allow tolling of SOVs on the Katy managed lanes and because the Katy is an interstate, the plan requires FHWA approval. As outlined in the 1998 Transportation Efficiency Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), the FHWA has the power to approve proposals to test the feasibility of new tolls on existing Interstate highways. HCTRA and TxDOT did seek FHWA approval for construction and operation of four toll lanes within the Katy; however, FHWA declined the request to toll only the four middle lanes on the interstate. FHWA interpreted the TEA-21 provision as giving it discretion over tolling proposals for interstate sections in their entirety, not just for the four center lanes.

HCTRA and TxDOT have subsequently sought and won FHWA approval for the proposal under the Value Pricing Pilot Program. In anticipation of the tolling of the four managed lanes, the two agencies requested a change in the Value Pricing Pilot Program already in place on the Katy. Review of this request by the FHWA’s Division Administrator has indicated that the current Value Pricing Pilot Program approval for the Houston area covers the changes anticipated by TxDOT and HCTRA to the Katy Freeway.

A third issue arises because FTA has a stake in the Katy: HCTRA and the FTA must negotiate a plan for transit access to the proposed expanded facility. For instance, will the hours for HOT operations be expanded? Will buses be able to use the facility for deadheading? What would the implications be if the number of buses on the facility increased significantly?

Finally, for the HCTRA proposal to move forward, a host of issues would have to be addressed collectively by TxDOT, HCTRA and the FHWA. FHWA has advised TxDOT and HCTRA to develop a Cooperative Agreement that would implement the project, detail its variable tolling strategy, discuss what parameters would govern the expenditure of Katy toll revenues, outline data collection efforts for the Value Pricing program, and address the need to collect tolls until the bonds are retired.

Background

California’s 91 Express LanesTM is a toll facility providing two lanes in each direction between the SR 91/55 junction in Anaheim and the Orange/Riverside County Line. The Lanes run for approximately 10 miles in the median of SR 91 and access points to the Express Lanes are provided only at each end of the facility (Figure 25). The availability of additional publicly owned right-of-way in this super congested corridor played a large role in the facility’s creation; the available ROW made it possible to provide two travel lanes in each direction.

The facility is fully automated and users must posses an electronic transponder to use it. Although the project is a toll facility, the 91 Express Lanes function similar to a HOT lane facility in that carpools are encouraged via lower toll rates; vehicles with 3 or more passengers may use the facility at a 50 percent discount.

The SR 91 corridor in which the Lanes are situated is one of the most heavily traveled routes in Orange County, California, and one of the most highly congested freeway corridors in California. On a typical day, roughly 250,000 vehicles use the route, and before the 91 Express Lanes opened, peak period delays between 20 and 40 minutes were common.

Launched in December 1995, the facility not only was a pioneer application of variable pricing in the U.S., but it also was funded only through private investments, the first project born from California’s AB 680 legislation passed in 1989. Because the project has been in operation for over six years, valuable usage data on the facility have been collected; these data have enabled researchers to evaluate many aspects of the Lanes’ operation and usage. For these reasons, the 91 Express Lanes project provides several insights into the planning and operation of high occupancy toll lanes.

When planning for the toll lanes began, the need for improvements in the highly congested SR 91 corridor had been evident for many years. Public funding was unavailable and would possibly not materialize in the coming years. California legislation AB 680, as well as innovative thinking from elected officials, planners, and the private sector, helped to make another solution and alternative funding possible.

In 1989, AB 680 authorized the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) to enter into agreements with private entities for the construction by private entities of four transportation demonstration projects, including at least one in Northern California and one in Southern California. The legislation authorized Caltrans to lease rights-of-way, grant easements, and issue permits to enable private entities to construct transportation facilities supplementing existing state-owned transportation facilities. The law also allowed Caltrans to lease those facilities to the private entities for up to 35 years. The legislation allowed private concessionaires to identify specific projects where a private facility would perform favorably. This is the path pursued for the 91 Express Lanes.

The $134 million 91 Express Lanes facility was one of the four public-private partnerships made possible by AB 680. It was built entirely with private funds through the California Private Transportation Company (CPTC), a concession company comprised of Peter Kiewit & Sons, Cofiroute Corporation, and Granite Construction, Inc. No significant public funds were used to build or implement the facility. The California Private Transportation Company and the State of California signed a 35-year franchise agreement under which the CPTC would construct and operate the facility on the leased median right-of-way.

One prominent factor contributing to the successful implementation of the 91 Express Lanes was the emphasis throughout the planning process on public involvement. During the evaluation and planning of any complex transportation project, planners and agency sponsors have many opportunities to drop the proposal from consideration. The absence of community support is often a major reason leading planners to abandon a potentially worthwhile proposal. In the case of SR 91, project sponsors clearly understood that public acceptance was critical if the effort to create a new transportation option in Southern California was to succeed. As the first privately owned and variably tolled high-occupancy vehicle facility, the 91 Express Lanes would depend on public approval and a supportive clientele.

Unlike the modest outreach efforts of the Sonoma 101 study discussed later in this chapter, the SR 91 example is notable for its direct efforts to assess public acceptance and to build public support for the plan early. From the initial planning stages through the operational phase of the project, the CPTC has continued to communicate with and seek input from the public and its client base.

When variable tolling strategies were first considered for the corridor, preliminary studies assessed travelers’ reactions to variable pricing. Comprehensive surveys of travelers and businesses were conducted, and a number of focus groups were convened. Project planners polled for public acceptance of the project, as well as the projected usage of a HOT lane facility and the willingness to pay for use of it. In fact, project sponsors have suggested that assessments of public support and willingness to pay were highly important factors in the decision to implement the project, as such polls helped assess the facility’s potential for profitability.

The planning process for the SR 91 facility also involved broad representation from community, political, government and industry interests. The stakeholders included in the process were the County Board of Supervisors, FHWA, Environmental Defense, the Reason Foundation, the Orange County and Riverside County Transportation Commissions, Caltrans, state legislators, local mayors and council representatives, and the International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association. A project newsletter produced throughout planning stages kept the public informed of SR 91 plans and progress.

Project sponsors have also noted that several local and state officials championed the project; the involvement of public figures willing to support the project gave the HOT lane plan a distinct advantage.

Public outreach remained a critical component during the project start up phase as well. Once the decision was made to launch the HOT lane facility, project sponsors reached out to national media and public policy makers. Press releases, speaker’s bureau engagements, and other public presentations were used to communicate the news of the lanes. Newsletters, radio advertisements, direct mail, and signage along the SR 91 route publicized the coming facility to potential users of the Express Lanes.

Since the lanes opened, the facility operators have surveyed customers every year to determine customer satisfaction and areas for potential service improvements. Also, every few years, non-customers have been surveyed to identify the incentives needed for them to use the 91 Express Lanes in the future.

Early in the lanes’ operation, regular mailings to customers and potential users reported any news about the facility, as well as any operational changes or adjustments to the toll structure. Now, service updates are provided to users via the facility’s website at www.91expresslanes.com, which is also a one-stop information center for the 91 Express Lanes. The website provides general information about the facility, allows drivers to apply for a 91 Express Lanes account and transponders online, supplies links to live traffic reports, and also enables pass holders to manage their accounts online. The facility’s operators also use electronic mail to send customers statements, policy updates, alerts and other important information from the 91 Express Lanes. Account holders can sign up for email notices through the website.

Since the 91 Express Lanes were opened in late 1995, the lanes’ operational and tolling structures have evolved in response to changing traffic conditions in the corridor and to the sponsor’s financial expectations. As operator of the system, the CPTC sets the toll rates, and uses the tolls to maintain an optimal level of service and revenue for the facility. Because the 91 Express Lanes is a fully automated toll facility, vehicles traveling on the facility must have a valid account and an electronic transponder (FasTrak Transponder) mounted on the vehicle.

The 91 Express Lanes offer three types of user accounts, each designed to accommodate customers based on how often they intend to use the facility. The Convenience Plan is designed for infrequent users, the Standard Plan is for motorists who use the toll lanes between 2 and 25 times per month, and the 91 Express Club plan is for frequent users. Monthly payment minimums and toll discounts vary with each plan. The 91 Express Lanes also offers special discounts for opening a new account with selected credit cards and for referring other customers. In addition, transponder holders are eligible for discounts at several local tourist, recreational and shopping venues. These user options demonstrate the facility’s efforts to meet customers’ individual needs as closely as possible.

While its original toll structure was successful, the CPTC has adjusted its tolls several times to optimize traffic service and revenue potential on the facility. The first toll increase came in January 1997 and three additional increases have followed. Whereas previously a single toll had applied for the entirety of the peak periods, in September 1997, tolls were adjusted hour by hour during the morning and evening rush hours. Additionally, in January 1998 the original provision that HOV 3+ (carpools of 3 or more persons) could travel for free in the Express Lanes was changed, and HOV 3+ vehicles were thereafter required to pay 50 percent of the basic toll.

Discounted tolls are offered not only to 3+ carpools, but also to zero emission vehicles, motorcycles, and vehicles with disability or veteran license plates. All other vehicles pay the regular tolls.

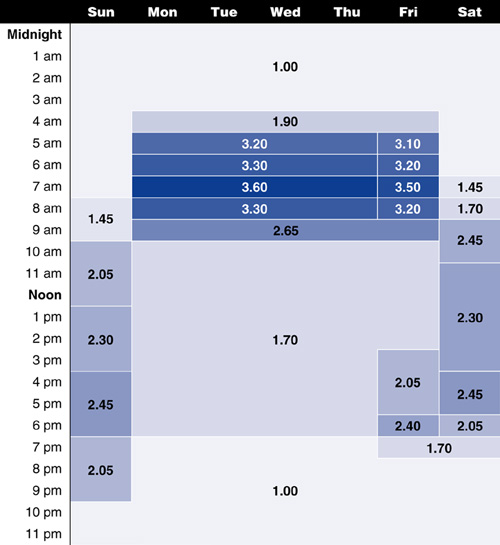

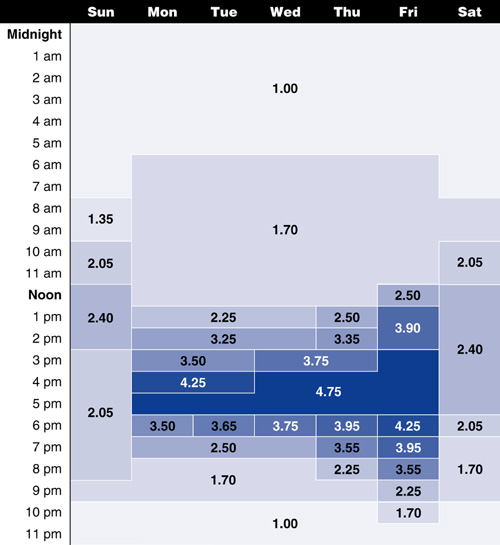

As of June 2002, tolls on the facility varied from $1.00 to $4.75 depending on the time of day and the day of week. The highest toll of $4.75 applies Monday through Friday from 5 to 6 PM eastbound (peak direction), when demand on the roadway is at its height. On Wednesday and Thursday, the $4.75 toll begins at 4PM and on Fridays, at 3PM. This suggests that the peak evening period expands as the week draws closer to its end. For the AM westbound peak, a high of $3.60 is charged Monday through Thursday from 7 to 8 AM (See Tables 7 and 8). In addition to reflecting higher demand during the peak commuting hours, tolls are also structured to reflect seasonal periods and seasonal trends in travel demand. The facility uses a simple tolling system, with all vehicles using the same entry and exit points. Tolls vary only by time of day and not by the length of trip on the facility, as all trips are the same length. While the tolls are not dynamic—i.e., they do not fluctuate in real-time based on real-time travel conditions—the CPTC regularly evaluates travel patterns and adjusts the toll structure accordingly. Overhead messages at each entrance to the Express Lanes show the current toll amount, so drivers can decide whether they wish to pay the current toll to speed up their trip.

Printed below, the eastbound and westbound toll schedules illustrate how variable tolls are used to regulate demand for the roadway during peak travel periods.

User Profiles

By the end of 1999, about 124,000 transponders had been issued by the CPTC for use of the 91 Express Lanes. Additionally, public toll road authorities in Orange County had by the same date issued 240,000 transponders that could be used on the public facilities as well as the SR 91 HOT lanes. Weekday two-way traffic on the SR 91 Lanes has averaged roughly between 25,000 and 35,000 vehicles, indicating that a small portion of SR 91 registered users actually use the Lanes on a given weekday. As with other HOT facilities, customers use the Lanes selectively.

Recent evaluations of the 91 Express Lanes also show that certain travelers are more willing to use the tolled facility. Females, particularly women aged 30 to 50, are more likely than other groups to choose a toll road. Additionally, other characteristics appear to affect a driver’s willingness to acquire a transponder to use the facility. Travelers with high incomes and higher education and who are middle aged and are commuters are more likely to acquire a FasTrak transponder.

One of the most important selling factors to users is the reliability of traffic conditions in the Express Lanes. Users value the security that they are unlikely to experience congestion in the Lanes and that any traffic incidents will be addressed quickly and cleared.

Since the launching of the 91 Express Lanes project, the institutional underpinnings of the facility have witnessed some challenges and changes. In fact, as of spring 2002, arrangements were being made for transfer of ownership of the lanes to a public agency. Although some of these issues have arisen several years into the lanes’ operation, they offer insights that may be useful to projects elsewhere.

First, the non-compete clause that was critical to the lanes’ potential for profitability became a sticky issue. As part of the agreement struck with Caltrans when CPTC initially agreed to finance and construct the toll lanes, Caltrans agreed to non-compete provisions by which it promised not to make improvements or add capacity to the existing general-purpose lanes on SR 91 without consulting with CPTC. Such improvements in the general-purpose lanes would harm CPTC’s ability to recoup investment in the tolled lanes, and thus the non-compete provisions were a primary way to safeguard CPTC’s interest in the Express Lanes. This non-compete agreement proved extremely contentious once it was used to thwart other capacity improvements in the corridor.

In 1999, Caltrans moved to add general purpose lanes in strategic locations on SR 91 to improve on and off ramp movements. The measures were viewed as necessary to address congestion in the SR 91 general use lanes. Discussions between CPTC and Caltrans about the need for and impact of the project failed, and CPTC sued to stop the plans. In a legal settlement, Caltrans withdrew the plans. The strife between the two institutions made explicit CPTC’s dependence on congested general purpose lanes to maintain high usership of the toll lanes, and the lawsuit may have damaged CPTC’s public image. Criticism was especially heavy from Riverside County, where most of the road’s users live, as Riverside commuters resented the high tolls and the state’s inability to address congestion in the corridor. In fact, Riverside County later sued to nullify CPTC’s contract to operate the Express Lanes, arguing that the agreement was an unconstitutional gift of public assets.

Secondly, when CPTC viewed refinancing as necessary for its financial health, the company was unable to win support for the strategy pursued. CPTC attempted to transfer ownership of the 91 Express Lanes to a non-profit organization called NewTrac in order to capitalize on better financing terms, and this was the object of criticism. NewTrac (a non-profit 501 c (3) corporation founded by a local group of independent businessmen) and CPTC had been in negotiations for NewTrac to purchase the lanes in December of 1999. The sale of the facility to a non-profit company would enable the new owners to reissue debt with tax-exempt bonds while the higher-interest bonds issued privately for construction of the facility were retired. NewTrac representatives projected that the transfer of the 91 Express Lanes from for-profit to non-profit ownership would generate $400 million to $500 million in surplus over the next 30 years of operation and that those funds would be returned to the public in the form of improvements to roads in the area. However, several aspects of the deal, including ties between CPTC and buyer NewTrac and the use of state sponsored bonds to purchase the Lanes, initiated concerns among state and local officials who had traditionally opposed the project. Ultimately, the California state treasurer blocked the deal.

Finally, in April 2002, the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) offered to purchase the 91 Express Lanes Toll Road and the operational franchise agreement from CPTC. OCTA first began considering a possible purchase of the Lanes in fall 2001, when its chairman requested OCTA staff to investigate ways to improve congestion in the 91 corridor, including a possible purchase of the Lanes. Several months later, OCTA entered into formal negotiations with CPTC to purchase the facility. While the sale will not be complete until the California state legislature grants approval to OCTA to levy tolls, OCTA has agreed to pay $207.5 million for the Lanes.

This planned transfer of ownership from a private to a public entity emphasizes some of the institutional issues that have been sticking points for CPTC. Purchase of the lanes by OCTA would negate the unpopular non-compete clause, allowing improvements in the general purpose lanes on the 91 Freeway. Moreover, not obliged as is CPTC to return profits, OCTA says it will adjust SR 91 toll rates to maximize throughput on the facility instead of profits. OCTA will also consider allowing three-plus carpools to use the facility for free once again. These proposed changes point to the difficulty faced by CPTC in trying to operate a HOT facility in a way that simultaneously met regional mobility needs and also hit private financial goals. OCTA has even suggested that tolls may be eliminated at the end of the franchise agreement in 2030 or sooner, if the agency receives outside funds to pay off remaining debt on the facility.

The institutional issues involving non-compete clauses, private ownership, and the sale of a facility by its original, private operator loom large in this case. The political difficulties that lie therein may be instructive.

First, operating a HOT facility presents its own challenges when the facility is owned and operated by a private entity ultimately interested in returning a profit. In this case, public acceptance of the facility wavered in response to legal wrangling with Caltrans and with Riverside County. The non-compete clause that was necessary to protect CPTC’s investment also stirred public resentment when it restricted Caltrans' ability to plan and implement capacity improvements on SR 91. OCTA officials are responding to precisely this conflict in moving to acquire the toll lanes.

Second, fostering public understanding and acceptance of the proposed transfer of ownership to the non-profit NewTrac proved difficult. The complexity of the financial advantages may have made it difficult to convey to the public the motivation behind CPTC’s decision to pursue that option. This reinforces the challenges involved when the private sector provides what has traditionally been accepted as a public good supplied by the government.

A third lesson to emphasize for future projects is that tolling structures must evolve as demand for the facility evolves over time. For example, although the 91 Express Lanes initially allowed HOV 3+ carpools to travel for free, this policy was adjusted after a few years. The decision to charge carpools 50 percent of the toll enabled facility operators to manage demand for the Lanes while also meeting revenue needs. Additionally, tolls on the facility have been adjusted several times since its opening. A HOT facility uses price to help distribute demand for the facility over time.

Finally, the success of the 91 Express Lanes depends on congestion in the general purpose lanes and on a toll structure that regulates demand so that the facility can always offer a time savings. These operational parameters are unlike those for traditional highways, and additional public education may be needed to explain them.

Background

Currently operated under the FasTrak Program of the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), the region’s metropolitan planning organization, the high occupancy toll lanes on I-15 have their origin in an HOV facility that first opened in 1988. The two lanes were constructed with Federal Transit Administration dollars in the median of an 8-mile stretch of Interstate 15, extending roughly from the juncture of I-15 and SR 56 to the north and I-15 and SR 163 to the south (Figure 26). Originally intended to attract carpooling commuters heading to downtown San Diego from points north, the HOV lanes were underutilized. To increase usage of the lanes and to supply funding for transit improvements in the I-15 corridor, SANDAG proposed converting the lanes to a HOT facility under the federal Value pricing Pilot Program. The HOV lanes were opened to paying solo drivers in December 1996. Project implementation was structured in two phases, and the use of toll collection technologies on the facility has evolved over time. The number of paying solo drivers has also increased over time. Today, the I-15 HOT facility uses a dynamic, real-time tolling structure, and toll revenue collected on the facility is used for transit service in the corridor including the Inland Breeze peak-period express bus.

Under the program’s first phase, called ExpressPass, users were issued a vehicle permit which allowed unlimited use of the HOV lanes. At first, only 500 monthly permits were sold, priced at $50 each. SANDAG issued 200 more permits in February 1997 and one month later raised the permit price to $70. In June of 1997, transponders were introduced on the facility. Whereas visual inspection was required previously to determine whether a vehicle had the required window decal permits, transponders allowed for electronic enforcement of permit requirements. The transponders also facilitated the collection of data about usage of the HOT lanes.

In Phase II of the project, begun in March 1998, variably priced per-trip tolls replaced the flat monthly fee. By identifying the project as a FasTrak facility, users from other FasTrak toll facilities in the state could also use I-15. Additionally, Phase II opened I-15's FasTrak program to unlimited membership. The lanes continue to operate in this fashion today. On normal commute days, the toll ranges between $0.50 to $4.00, depending on current traffic conditions; however, tolls may be raised up to $8.00 in the event of severe traffic congestion. To maintain free-flow on the FasTrak lanes at all times, toll rates are adjusted every 6 minutes in response to real-time traffic volumes. The actual toll at any given time is posted on the roadside signs to inform drivers of the current price for using the lanes. To preserve the carpooling incentives that existed with the original HOV lanes, carpools and other vehicles with two or more occupants may always use the FasTrak lanes for free. The lanes operate only during peak hours in the direction of the commute. From 5:30 AM to 11 AM, all vehicles in the HOT lanes travel southbound; from 11:30 AM to 7:30 PM, all vehicles travel northbound.

Electronic signs at the entrance to the HOT lanes notify motorists of the current toll as they approach the toll lanes. Motorists enter the HOT lanes at normal highway speeds. Toll collection occurs when the motorist travels through the tolling zone, where overhead antennas scan the windshield-mounted transponder and automatically deduct the posted toll from the motorist's pre-paid account.

Like the SR 91 Express Lanes which came before it, the I-15 HOT lane initiative also included early and aggressive efforts to assess public opinion and potential usage of the lanes before the facility was launched. Additionally, the implementing agency SANDAG also has paid close attention to marketing issues throughout project implementation and operational phases.

As a first step, SANDAG contracted with a consultant to collect baseline market survey data. Commuters in the I-15 corridor were queried in focus groups, telephone surveys, and intercept surveys on their attitudes toward variable tolling and traveling in the corridor. The findings from these pre-project studies formed the basis of strategies for pricing and for customer communications. Second, preparation for the first announcement of the project to the press in November 1996 involved significant preliminary planning; SANDAG worked with consultants to develop a project identity and background materials, as well as to formulate a promotion plan for Phase I of the project. A newsletter, the I-15 Express News, was used to introduce the ExpressPass Program as well as to provide updates about the facility as toll operations evolved. Town hall meetings were also held for communities in the corridor to publicize project. To prepare for Phase II, when the facility transitioned from a monthly pass and to per trip tolls, SANDAG used radio advertisements and a name-the-bus contest to raise public awareness of the coming changes.

The SANDAG I-15 FasTrak Online website provides full documentation of the supporting studies that were used to formulate tolling schedules, marketing plans and promotional materials. The reports are part of the I-15 Value pricing Project Monitoring and Evaluation Services and most are available in pdf format. This online library, found at http://argo.sandag.org/fastrak/library.html, also contains downloadable reports on traffic and operations issues during the project's history.

Political Champions

The evolution of the I-15 HOT facility project demonstrates the important role that a political champion can play. The elected official who shepherded the I-15 HOT lane proposal through the SANDAG Board of Directors remained an important figure to secure needed support and legislation at the state level.

The origins of I-15’s HOT facility lay in SANDAG efforts in the early 1990s to develop air quality control plans. A local elected official (who also served as a SANDAG board member) was concerned with the lack of transit and had proposed construction of a trolley in the I-15 corridor. The existing HOV lanes were underutilized at the time, in part because of limited entry possibilities, and the I-15 general purpose lanes were often congested during peak periods. Aware of the Value pricing Pilot Program (now called the Value Pricing Pilot Program) created by ISTEA in 1991, the SANDAG staff proposed selling the HOV facility’s excess capacity and using the funds to support the transit service desired in the corridor. Shepherded by the supportive board member, the SANDAG board passed a resolution in May 1991 to pursue a Value Pricing Demonstration. The project would toll single-occupant vehicles for use of the I-15 HOV lanes and use the toll revenue for transit service in the corridor.

Although SANDAG’s initial grant application to the Value Pricing Pilot Program was denied in 1993, SANDAG won federal approval and a $7.96 million grant in January 1995, after the FHWA revised the eligibility criteria to include HOT lane projects. In spite of the federal green light for the project, state enabling legislation was needed to allow the HOV lane conversion at the center of the SANDAG plan. (California state law stipulates that only 2+ person carpools are permitted in HOV lanes.)

The same elected official who championed the project on the SANDAG board also played a key role in moving the project past the state level hurdles. After moving to a position in the State Assembly, the official sponsored the original enabling legislation for the HOT facility. Passed in 1993, Assembly Bill 713 authorized a four-year demonstration project from 1994 through 1998. The statute also required that the lanes maintain a particular level of service for HOV users, and that project revenues be used for transit service and HOV facility improvements in the I-15 corridor. When the demonstration project was due to sunset in 1998, the same elected official was an important advocate for its extension through January 2000 via AB 267. Since then, the legislation has gone through other rounds of sunset dates and extensions, and each time supporters in the state assembly and senate have been important backers.

As noted above, the I-15 FasTrak Online website provides access to numerous studies, reports and evaluations completed during the development of the I-15 HOT lanes. The reports discussing "Implementation Procedures, Policies, Agreements and Barriers" offer particular insight into lessons useful both for the I-15's future and for the development of similar projects elsewhere. Some of these findings include:

Given the growth in vehicles using I-15 over the last decade and the success of the FasTrak HOT lanes on the highway, SANDAG and Caltrans are now considering plans to expand capacity in the I-15 corridor, with emphasis on accommodating HOV travel. As of early 2002, over 250,000 vehicles a day travel on Interstate 15, representing an increase of 100,000 vehicles per day from 10 years ago. Forecasts suggest that future traffic volumes on I-15 will continue to increase, as will the number of people living in San Diego County.

The plans under consideration, known as the "I-15 Managed Lanes," would extend the I-15 HOT lanes north as far as SR 78 in Escondido and would create a 20-mile, two-directional managed lane facility. The proposal would use advanced technologies to monitor traffic service on the road, detect problems, and keep vehicles moving. The system would allow changing the lane configuration to accommodate peak directions and would also provide more entry and exit points to the lanes. To evaluate this proposed expansion, a consultant team is currently studying the proposal's operational and financial feasibility.

An 800-person telephone survey of I-15 users conducted in fall 2001 indicate that the majority of motorists support the lanes, and that motorists with the most extensive experience with the FasTrak lanes are the most ardent supporters. Ninety-one percent of users supported having a time saving option on I-15, and 66 percent of I-15 users who do not use the FasTrak lanes support them. Moreover, I-15 users overwhelmingly support the facility’s expansion.

Background

Constructed in the 1950s as a four-lane highway, the US Route 101 corridor through California’s Sonoma and Marin Counties has experienced significant residential and commercial development and considerable population growth in recent decades. The corridor provides vital connections for commuters among Marin, Sonoma, and San Francisco Counties and is an important link in the regional transportation system. As in many corridors serving high-growth suburban locations throughout the country, increasing numbers of drivers and vehicles together with sharply rising vehicle-miles traveled have produced severe traffic congestion on the roadway.

While earlier planning studies had proposed the addition of new high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes in the corridor, scarce funding prevented the construction of additional lanes. Consequently, in December 1995, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC)—the region’s metropolitan planning organization—and the Sonoma County Transportation Authority (SCTA) began discussing the possibility of using tolls to help finance a new HOT lane in the corridor. In 1997, as part of the FHWA Value Pricing Pilot Program, a study was initiated to examine the proposed addition of priced express lanes in the median of US 101, from the Marin County line to just north of the City of Santa Rosa in Sonoma County.

Completed in January 1999, the Sonoma County US 101 Variable Pricing Study found that toll lanes in Sonoma County from Windsor to SR 116 in Petaluma (approximately 25 miles) would provide congestion management benefits and produce revenue for all operating and substantial capital costs (Figure 27). Although Marin County initially declined to consider the HOT lanes due to concerns about additional highway capacity and growth inducement, Marin subsequently decided to study HOT lane alternatives also. An additional 11.5 mile segment in Marin and Sonoma counties known as the "Novato Narrows" was examined in the study US 101 Variable Pricing Study: State Route 37 to the Petaluma River Bridge. The study found that the extended lanes would be physically and financially feasible, though as a stand-alone project they would not perform as well financially as the 25-mile Sonoma segment.

Although the Sonoma effort did not invest significant effort in public outreach, it did address essential technical aspects of HOT lane feasibility. After preliminary analysis showed that further study of the HOT lane concept would be useful, a consultant was brought on to conduct a variable pricing study for the corridor, and a budget of $280,000 was established for the effort.

The consultant screened initial alternatives using the following evaluation criteria, which bear witness to the multiple objectives often involved in a HOT lane endeavor:

After initial screening, two main alternatives and their variations were selected for further evaluation. Alternatives 1 and 2 differed primarily in length of the HOT lane and in the number of access points. Alternative 1 featured a 15-mile facility with the possibility of (1a) four or (1b) six access locations. Alternative 2 featured a 25-mile facility with the possibility of (2a) five or (2b) eight access locations.

The study considered two design alternatives, median lanes and a more expensive option which would upgrade inside and outside freeway shoulders. Capital cost estimates ranged from $85 million to $179 million depending on the design alternative, and the average operating and maintenance costs estimates ranged from $1.6 to $1.8 million per year.

Travel forecasts identified the likely demand for each alternative in 2005 and 2015. Demand estimates found that 45 percent of the HOV-lane users would be 2-person carpools and that to maximize revenue potential, 2-person carpools should be charged the same toll rate as single occupant vehicles. Carpools of 3+ could be allowed to use the lane for free.

The feasibility study considered two tolling options: (1) a flat per-mile toll that was higher at certain times of day, but remained constant for all highway segments, and (2) a variable per-mile rate that varied by time of day and by corridor segment, depending on congestion at specific locations.

Revenue projections found that the variably priced toll lane would produce more toll revenue, as well as provide more reliable speeds in the lane. Annual gross revenues from revenue-maximizing tolls (using variable tolls) ranged from $4.6 million to $5.8 million in 2005, depending on the alternative and variation considered. The study emphasized revenue maximization as tolls were considered primarily so the facility could pay for itself.

A financial analysis of the four alternatives considered estimated traffic growth, borrowing costs, inflation, and the application of a flat or variable toll. The analysis assumed the toll lane would be financed using bonds supported by the lifetime revenues of the facility. The analysis found that the variable toll generally produced a higher yield and that the variable toll alternatives could actually pay for most or all of a basic HOV lane median widening project and a substantial portion of the more expensive design alternative.

The feasibility study also considered what institutional arrangements would be needed to support the toll facility. Aside from state-owned toll bridges, the state of California operated no toll roads at the time of the study (1997). Thus, an HOV/Toll lane would likely require some new institutional arrangements. The study suggested that because the projected revenue for the project was substantial, defraying all of the project’s operating costs and a large portion of its capital cost, it might be possible to attract private sector capital. Even if private sector investment were not needed or sought, the report noted that possibilities for private sector participation existed in some elements of the project, such as operations and maintenance.

Several possibilities were examined in the study:

1. Publicly financed, developed, owned and operated HOV/Toll lanes. Under this option, Caltrans would develop, finance, own and operate the HOV/toll lanes. First call on the funds would be for facility maintenance and operations. The net toll revenues would be available for further corridor improvements.

2. Private or public/private finance, ownership or operation. The report suggests that, if the corridor continues to suffer from limited access to new funding, the facility could rely on toll revenues for its development and finance. A number of ownership and operating relationships could be used to engage the private sector. The pattern of ownership would affect risk-sharing, financing terms, and access to types of financial instruments. Options would include:

Because there has been no movement to implement the HOT lane proposal, these institutional frameworks have not received further consideration.

Once the Sonoma County study established the potential feasibility of toll lanes on US 101, Marin County was encouraged to evaluate the potential for HOT lanes on an additional 11.5-mile segment in Marin and Sonoma counties known as the "Novato Narrows." That study, US 101 Variable Pricing Study: State Route 37 to the Petaluma River Bridge, also found that the lanes would be physically and financially feasible.

The variable pricing study conducted for the Marin-Sonoma section of US 101 considered a no-build alternative along with (A) north- and southbound free HOV lanes, (B) north- and southbound tolled and buffered HOV lanes, (C) one reversible free HOV lane, and (D) one reversible tolled HOV lane. The analysis identified travel demand forecasts for the years 2005 and 2015, capital costs, operations and maintenance costs, and the operational feasibility of each scenario. For the tolled scenarios (B) and (D), the study analyzed revenue generation using variable tolls that would optimize revenue and regulate demand, so the lanes would retain travel time savings to attract motorists.

Considering the effects on congestion, the study found that when compared with the base case/no build scenario, both the free and the tolled HOV lane options provided substantial travel time savings to users (approximately 10-12 minutes over the 11.5 miles) and significantly increased person-throughput.

Like the Sonoma study before it, this analysis also considered (1) a flat tolling option that changed by time of day only and (2) a variable toll that changed by time of day and by corridor segment, depending on congestion levels. Like the Sonoma study, the variable toll in this case was also expected to generate slightly higher revenue although it would not produce a significantly different performance level compared with the “flat” time-of-day toll.

A unique component of the Marin study was the assumption that passenger rail service would be operating in the proposed HOT lane corridor in 2015. Citizens in Marin and neighboring counties have called for establishing passenger transit service using the Northwestern Pacific Railroad right-of-way in the US 101 corridor. Although no definitive plans have been adopted for the right-of-way, the Marin study considered the effect of the proposed toll lane on rail ridership, concluding that the travel time savings offered by the free HOV lane or toll lane options would likely divert a small number of potential rail riders to the highway.

Another prominent issue that arose in this study was anti-growth sentiment. In Marin County, proposed highway expansions have received intense public scrutiny over potential growth inducement. The US 101 HOT lane proposal also raised such concerns in Sonoma. Resistance to growth and sprawl subsequently influenced the selection of proposed access points for the Sonoma HOT lanes, as access points were discouraged in rural and other areas where growth was not desired. This instance suggests the importance of addressing local concerns in HOT lane proposals and plans, and also shows how HOT facilities and local land use plans might be coordinated to steer growth toward some areas and away from others.

Although both feasibility studies indicated the encouraging potential of HOT lanes on US 101, toll lanes have not been advanced. Understanding why provides insight into the political and public dimensions of HOT lane projects that can determine whether an innovative project like toll lanes is advanced.

While elected officials showed interest in tolled high occupancy vehicle lanes for the US 101 corridor and funded two studies to determine their feasibility, HOT lanes came to be viewed as a funding measure of last resort. There was skepticism among officials that the public would accept tolled highway lanes. Moreover, at the same time that variable pricing initiatives were studied for the 101 corridor, local officials also sought funding for US 101 improvements through sales tax referenda in Sonoma and Marin Counties.

Officials considered a sales tax a more conventional and palatable way to raise money for the needed lanes, because the public was more familiar with this financing method. However, voters rejected sales tax initiatives in 1998 (Sonoma and Marin) and in 2000 (Sonoma). Another sales tax referendum may appear on the Sonoma County ballot in 2002.

Additionally, local officials also sought state funding for the highway widening, and, partial state funding for some segments has since been secured. The 1998 Regional Transportation Plan allocated some funding to widen Highway 101 in Sonoma County, building carpool lanes along more than two-thirds the length of Highway 101 between the Marin County line and Windsor. While the additional funding needed to complete the project is uncertain, local officials have not pursued the tolling option, and the variable pricing studies have not been publicly promoted.

As a matter financial pragmatism, the concurrent pursuit by local government of tolling studies, dedicated sales tax, and state grants to fund the proposed road improvements is logical; however it may have hampered the advance of a toll lane initiative in this case. For the time being, the local political leadership seems reluctant to initiate public discussion of tolls on the 101 while voters are also considering sales tax measures. As with many HOT lane initiatives, there is also general hesitation to pursue a tolling plan that may be perceived as another tax rather than as another travel option.

Public outreach regarding tolled express lanes on the US 101 has also been extremely limited. Public input was sought during the feasibility study process, but this was accomplished largely through a 25-member advisory committee composed of members of business, environmental, and labor groups, political representatives, and civic groups. Study sponsors chose not to widely publicize or promote the HOT lane concept, and the absence of a visible and vocal public champion created an additional hurdle for the Sonoma 101 HOT lane proposal.

Background

The planning for high occupancy toll lanes in Denver, Colorado, provides a unique case study demonstrating the important role played by state legislation in stimulating interest in HOT lane solutions. Unlike cases where the impetus for a HOT project or proposal arose from congested conditions on a specific facility, the Denver example was greatly accelerated by a piece of state legislation and the state legislator who championed it. Independently, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) had begun investigating the conversion of I-25 lanes north of Denver from HOV operation to HOT operation, in order to better utilize that facility.

In 1999, one Colorado state senator initiated efforts to launch a bill designed to address the underutilization of high-occupancy vehicle lanes in the state. The bill, known as Senate Bill 88 (SB 88) and supported by a number of other state legislators, aimed to legislate the application of value pricing to make fuller use of under-utilized HOV lanes in the state. The bill's sponsor pointed in particular to several HOV facilities in the Denver metropolitan area that often operated below capacity. These included HOV lanes on I-25 north of Denver, US 36 connecting Denver and Boulder, and on Santa Fe Drive.

Passed in 1999 with support of CDOT, SB 88 mandated the CDOT to examine the desirability and feasibility of implementing high occupancy toll lanes. The bill required CDOT to solicit expressions of interest in converting an existing HOV lane to a HOT lane using a private contractor. In absence of a qualified bidder to operate the lane, CDOT would possibly have to undertake the operation of the HOT facility. Precisely these points of the bill make it unique: (1) The bill did not seek simply to open the HOV lanes for use as general purpose lanes, but rather acknowledged the available capacity on the HOV lanes as a resource and a commodity; and (2) The bill required CDOT to seek the participation of the private sector in the conversion from an HOV-lane to a HOT facility. In fact, the senator who championed the bill noted that using a private contractor to convert and operate the lane would spare taxpayers the associated financial obligations. With the assistance of CDOT’s value pricing expert, the state senator was able to forge a unique coalition, including the environmental community and trucking interests, that was essential in getting the bill passed.

As in other U.S. metropolitan areas that have begun to examine the potential application of HOT facilities in their transportation network, growth has been a primary factor leading Denver to consider HOT lanes. From 1990 to 1996, population in the Denver metropolitan area increased 14.5 percent to 2.13 million people. Some project population to grow another 30 percent by 2020, and employment in the region is expected to increase 35 percent by 2020. At the same time, vehicle miles traveled have increased at a much higher rate, rising 5.2 percent annually from 1990 to 1995.

In June 1999, CDOT launched the Value Express Lanes Study to examine the potential application of HOT lanes in the Denver metropolitan area. As indicated in the statute that prompted the study, the policy premise underlying Value Express Lanes is to maximize the use of HOV lanes by allowing SOV drivers to pay to use them, while also maintaining the incentive to carpool and take the bus. Funding for the study came from CDOT and the Federal Highway Administration, and study partners included the Regional Transportation District (RTD), the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG), and the US 36 Transportation Management Organization (US 36 TMO).

The study included two phases. The first phase would assess the potential application of HOT lanes in a number of corridors throughout the Denver region, including Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Denver, Douglas and Jefferson counties. The aim of this macro study was to identify candidates that could be recommended for future project and corridor planning efforts and more focused feasibility studies. The second phase involved a more detailed feasibility analysis of HOT lanes on US 36 and north I-25's existing HOV facility.

The first step in identifying candidate HOT facility projects involved a broad look at corridors in and around the Denver metropolitan area. This regional assessment consisted of identifying and screening twelve potential corridors in order to select candidates for more advanced feasibility studies. This first cut proceeded with steps to:

1. Identify potential candidate corridors;

2. Develop a criteria matrix;

3. Collect corridor data; and

4. Evaluate the corridors.

After identifying the twelve corridors to be studied, located within CDOT's Denver metropolitan region, criteria were developed by which each candidate corridor could be evaluated. For each criterion, each candidate corridor received a score of high, medium, or low. The criteria addressed the factors that might make a corridor more suitable for HOT lane application. They included:

1. Traffic/excess capacity: Traffic conditions on each corridor were examined, including peak hour volume to capacity, estimated daily hours of congestion, and the length of the congested portion of the facility. High scoring corridors exhibited a peak hour volume to capacity ratio of 0.9 to 1.0 or greater, experienced congestion for at least 2 hours in the AM or PM peak, and had congested segments that stretched for 5 to 10 miles.

2. Corridor/Transportation Planning: This criterion examined current planning efforts for each corridor. Corridors scored higher where short- and long-term investments under consideration included or could include an HOV-lane alternative.

3. Right of Way: The study assumed that Value Express Lanes would not take away general purpose lanes, implying that any HOT facility application would require new capacity. For this reason, the availability of right of way in the candidate corridors was an important consideration. Corridors received higher scores for this factor when they had adequate right of way to construct additional lanes or when only a small amount of right of way would need to be acquired to accommodate a HOT lane.

4. Design considerations: This criterion considered how each proposed corridor could connect with the larger transportation network. Candidates that received higher scores were those corridors that would or could connect to other existing HOV facilities; link to other facilities and freely accept traffic from and/or supply traffic to those facilities, and absorb and integrate traffic accepted at entry points.

5. Travel behavior: This factor considered travel patterns in each corridor. Corridors that served commuter travel characterized by heavy flows in a peak-dominant direction or that served a large proportion of long distance trips were considered better candidates.

These criteria make clear how a HOT facility might be expected to perform in the Region. Additionally, assumptions outlined in the screening analysis also make clear some of the policy choices underlying the study. For example, the study assumes that a HOT application would be most compatible with an existing or planned HOV lane, that buses and carpools would be expected to use the HOT facility for free, and that some recurring congestion is necessary in order for travelers to be willing to pay a toll to avoid the congestion. Also, the study explicitly notes that a HOT lane cannot replace an existing general purpose lane, however where a new general purpose lane is currently planned a HOT lane should be considered in future alternatives analysis. The study also notes that costs were not used in this first screening, given the assumption that few HOT lanes would recover the full cost of adding lanes through tolling.

After relevant data about each corridor was collected and reviewed, each corridor was assessed for its suitability to serve as a Value Express Lanes candidate. Three corridors scored in the high range, indicating potentially high compatibility with Value Express Lanes.

These corridors showed sufficient promise for HOT lane application due to their high traffic volumes, high proportion of longer trips, encouraging forecasts for carpool and bus use, and/or sufficient right of way to accommodate a HOT lane.

Phase two of the Value Express Lanes Study looked specifically at the I-25 /US 36 corridor leading from downtown Denver to Boulder, linking two of the three largest employment centers in the Denver region (Figure 28). The corridor is heavily used by regional transit service, and the US 36 portion was recently the subject of a major investment study that recommended bus rapid transit, regional rail, road improvements and a bikeway for the corridor. The challenge of the Value Express Lanes Study was to consider a HOT application on this facility that acknowledged recent US 36 MIS recommendations and could meet existing commitments to level of service B on I-25’s Downtown Express.

Since 1995, I-25 has hosted the FTA funded Downtown Express Bus/HOV facility. The facility has experienced tremendous growth in users since its opening. Three years after opening, it carried 7,000 vehicles per weekday, almost twice as many as when it first opened. By 1998, daily ridership counting bus passengers and carpoolers totaled over 24,000 people per day. Because this facility was built with federal funds, the RTD is obligated to meet level of service B for buses and carpools.