8. ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

8.1 Introduction

The previous chapters have described the structure and organization of the RFC Project, the evolutionary history of the development of the project, and the factors that motivate and support a viable partnership. The discussion has noted many of the challenges that have been faced by the partnership in the RFC developmental process. An important objective of this evaluation, as noted in Chapter 2, is to assess how the project partners “identify, address and resolve issues associated with planning for and implementing the RFC Project.” This chapter focuses on the more important of these issues: technology risks, finances and fares, operational challenges, and relationships with the vendor and the agencies’ customers.

8.2 Technology

8.2.1 System Specification and Procurement Approach

In very broad terms, agencies wishing to procure and implement a fare card system can proceed in one of two contrasting ways:

- Procure a particular vendor’s “off the shelf” system; tailor it to agency characteristics; and adapt their business and other functions to make use of the system; or

- Specify the desired system capabilities based on agency business processes, operations and needs; select a vendor to develop a system that provides the desired capabilities; and integrate it with agency functions.

The RFC Project adopted the former approach and selected hardware and software from a vendor who, in close consultation with the RFC Project partners, is modifying portions of existing hardware and software to accommodate the RFC Project’s business and operating rules. The partner agencies felt that fare collection and processing were core transit agency functions.[39] In consideration of the potentially large impact that a fare card system could have on these functions, they preferred to conceptualize the agency business processes and fare card system as a comprehensive whole. They felt that this approach would ensure that agency business processes would be most able to take advantage of the fare card system technology, and that the fare card technology would best support the agency business functions.

Accordingly, the partner agencies proceeded by (1) creating a vision of how a fare card system could be integrated with and support their functions and operations; (2) developing detailed system requirements, based on an analysis of how fare card technologies could best be applied to improve the performance of the agencies’ core business functions; and (3) deriving corresponding technology specifications. The detailed technology specifications that resulted from this analysis were later included in the Request for Proposals (RFP).

The development of a system vision, functional requirements and preliminary specifications were significant milestones in the overall phasing of the RFC Project. This research, analysis and consensus-building effort took the partner agencies roughly one year to complete, working closely with a technology consultant. Some of the smaller partner agencies initially found the technology issues daunting, but over time they learned from the larger and more technologically sophisticated partners.

In parallel with the requirements analysis and prior to issuing the RFP, the agencies also investigated the potential vendors and the types of systems that each offered. In view of the long-term relationship that would be created by the choice of a vendor, the partner agencies felt that they should become as familiar as possible with the candidates, their technologies and their systems.

Conducting the procurements for this project has presented a challenge as well, since the Regional Team lacks the authority to make procurements on behalf of the partner agencies. On the other hand, individual agency procurement policies vary from one agency to another, and agency policies may be unable to accommodate the regional budget for acquiring the needed goods and services. This is essentially an unresolved issue. Recent procurement needs have been handled by “tagging on” to existing agency contracts. Nevertheless, the difficulty agencies have faced in handling the services and materials procurement requirements of the RFC Project remain a very significant institutional issue.

8.2.2 Hardware / Software Standards

There are currently few adopted standards concerning the hardware and software interfaces between different components of a fare card system. While fare card standards are in development, through the American Public Transportation Association’s (APTA) Universal Transit Farecard Standards (UTFS) Program, no UTFS standards were sufficiently complete in time for this project. During the Puget Pass program, this lack of common standards meant that the incompatible technologies used by the various partner agencies created a barrier to communications between agencies. In developing the procurement for the RFC system, the partner agencies wanted to avoid creating a similar situation.

In the RFC Project, the vendor-provided on-board equipment includes:

- the driver display unit (DDU), which is the device that bus operators use to communicate with the system; and

- the fare transaction processors (fare card readers), which access information on a passenger’s fare card and make it accessible to the rest of the RFC system.

Partner agency vehicles include a variety of other devices, such as radio systems and vehicle destination displays.[40] Operators currently have to initialize these different systems individually, which wastes time and is a potential source of errors. The RFC Project RFP required that, following an operator’s logon to the DDU, the DDU should be able to initialize other on-board systems itself, without requiring further operator intervention. This obviously means that the other systems must be able to interface with the DDU. The agencies also required the vendor to integrate their systems with the agencies’ existing or planned on-board technologies. This requirement was the driving force behind the biggest change the vendor had to make to their off-the-shelf technology.

In the absence of industry-wide interface standards, the project partners decided to impose the requirement that the hardware and software products of different vendors be able to inter-operate. This requirement also ensured that the RFC system would be able to evolve over time, for example if new agencies or new modes became part of the system. This is different than requiring the different vendors to comply with a single set of open standards. The partner agencies also attempted to introduce standards when possible, but opportunities for this were limited because of the legacy hardware and software in use by the various agencies.

According to the RFC Project vendor contract, the system vendor bears responsibility for ensuring that all other on-board systems interface properly with the DDU.

The RFC Project “back office” and transaction clearinghouse software was held almost to the software standards of a financial fiduciary institution. Again, there is no industry-wide data standard for registering transit fare transactions. The vendor software was required to interface with several existing systems other than those on-board the bus, such as the Washington State Ferry system gates and their back office system, and Sound Transit’s ticket vending machines. An additional important requirement was that the software should allow each individual partner agency to keep its independent fare structures and policies.

8.2.3 Software Specification Via Output Reports

The system software requirements were specified, in part, by defining in detail the reports that the RFC system would be expected to produce in order to provide data needed to support the partner agencies’ business processes. By working “backwards” from these report requirements, the system’s data collection and storage needs could be deduced, and the system database functional requirements could be derived. Moreover, with this approach the software’s report generation functions were explicitly specified from the beginning, rather than added on as a cost-inflating afterthought, as sometimes happens in system procurements.

8.2.4 Technology Risk Management

The procurement, initial deployment and ongoing operation of the RFC Project presented the partner agencies with new hardware and software technology and the need to address risks associated with them.

The RFC Project partner agencies decided to procure an “off-the-shelf” fare card system, selectively modified to accommodate technology specifications from their core business needs. The agencies felt strongly that their business needs should determine the system’s features and capabilities. They preferred to accept the risks associated with some system modifications rather than trying to adapt their business processes to an already developed but possibly mismatched system.

The RFC Project’s Request for Proposals (RFP) required responders to post a $10 million performance guarantee and meet a restricted and demanding milestone payment schedule. This was done to ensure that only well-established, financially robust firms would reply. The partner agencies recognized that their procurement approach might exclude less-established vendors even if they were viable and had interesting, innovative technology, but the partner agencies accepted this in order to reduce the risk of selecting a financially unstable vendor. It turned out that the restricted milestone payment schedule was more troublesome for proposers than the performance security.

Three firms responded to the RFP. One was initially deemed non-responsive. The partner agencies conducted an extensive process of proposal review and revision and two Best and Final Offers (BAFOs). An Apparent Successful Proposer was identified and the agencies concluded negotiations with this vendor. The selected vendor had already developed and deployed (in other locations) most of the hardware and some of the software components that would be used in the Central Puget Sound RFC system. Because of this prior experience, the RFC Project partner agencies avoided much of the risk associated with unproven technologies, and benefited from the earlier system development efforts.[41]

Much of the new software was developed for the RFC system to implement the agencies’ business rules, and to interface with their network and other onboard systems. Most or all of this software would have had to be developed in some form even if an unmodified off-the-shelf system had been chosen; the associated development risks can thus be considered unavoidable.

The already-proven reliability of the technology was reflected in the design of the plans for the RFC system beta test. Beta tests are normally intended to discover and correct a wide variety of system errors and defects, and can involve considerable and extended efforts to modify problematic technology. In the case of the RFC Project, however, the beta test is not intended as a test of the technology, and it is not expected to lead to substantial debugging efforts. Rather, it is intended to verify the overall functionality of the RFC system (technology, operating procedures, business processes) as a whole. The test will involve equipping approximately 400 buses (a subset of each partner agency’s regular revenue service) with modified DDUs and card transaction hardware. The software that carries out the back office operations and interfaces with the partner agencies’ legacy systems will be fully implemented. Some customer service terminals will be deployed. The beta test will run for a relatively short time: a two-week break-in period, approximately six weeks for the basic system testing and up to three months total for additional data collection. During or following the beta test, bus operator focus groups will be held to discuss potential DDU user interface issues, and these may lead to minor software revisions. These are the only technology fixes that are anticipated to be required during the beta test. Currently, the beta test is expected to occur in the third quarter of 2006.

The greatest technology risk and concern has been that the vendor might default on the contract, leaving the partners with a “black box” software system that they would be unable to continue to develop. The vendor, on the other hand, considered its system source code to be proprietary.

This risk was managed via a software escrow agreement. The vendor contract required the vendor to deposit the system source code and associated documentation with a software escrow company, and to update and refresh these files at each milestone payment until Full System Acceptance. During the operating phase, the escrow must be updated with each system upgrade. Under the terms of the contract with the escrow company, the agencies could periodically ask the company to verify that the source code compiles correctly, and that its functionality matches that of the currently deployed system. The contract also stipulates that, if the vendor defaults, the escrowed code would be released to the partner agencies. They also have the option to purchase the software outright at the term of the ten-year operating contract.

This escrow arrangement is somewhat complex (as it involves a three-party agreement) and can be costly, contingent upon the frequency of full build and verification services. However, it was felt to be the most satisfactory way for both the partner agencies and the vendor to manage the risks associated with the RFC system software. Some lessons regarding the risks associated with a fare card technology include the following:

8.3 Financial Issues

From the revenue allocation procedures to treatment of funds flowing through the fiscal agent, in designing the RFC Project, partner agencies have dealt with numerous issues of central importance to their financial operations. In doing so, each of the agencies recognized that in order to take advantage of the RFC system technology, each must adopt new business rules to deal with pressing issues related to, among other things, revenue allocation, operation of the fiscal agent, interactions with the revenue clearinghouse and potential partnerships with third party retailers. Resolution of these issues affects each agency’s bottom line at a time when public transit agencies are experiencing constrained resources. To the extent the resolution of an issue holds negative consequences for an agency, their fares are placed in jeopardy.

Lesson: Anticipate and Manage RFC Technology Risks

- Recognize that the risks of developing a customized fare card technology (hardware and software) are potentially much greater than the risks associated with accepting an off-the-shelf technology that is already proven.

- A modified off-the-shelf or customized system has the advantage of closely meeting the specified needs of the regional partnership, along with the disadvantage of needing more development and testing to be certain that it does what it is supposed to do.

- Establish a sufficiently large performance security requirement with the system RFP to assure that only financially secure firms are likely to respond. The down side is the likelihood that some firms with new technologies may be excluded from further consideration, and competition may be limited as it was in the Central Puget Sound case.

- All else equal, it is preferable to select a vendor with established electronic fare card systems deployed elsewhere that also meet most of the requirements of the project. This helps avoid the risks of adopting unproven technologies.

- Customized software may need to be developed in order to accommodate the partners’ existing legacy systems with which it must be integrated. These risks usually cannot be avoided, though in the case of Central Puget Sound not all the partner agencies had legacy integration issues.

- Establish an escrow account for source code, documentation and other trade secrets to protect against the risk of vendor default, and contractually require the vendor to deposit its proprietary source code, build documentation, and periodically update them.

- Require a conservative payment schedule that allows for major milestone payments at limited points in the contract, each associated with a significant and satisfactory completion of work.

- Require extensive and comprehensive insurance coverage from the vendor.

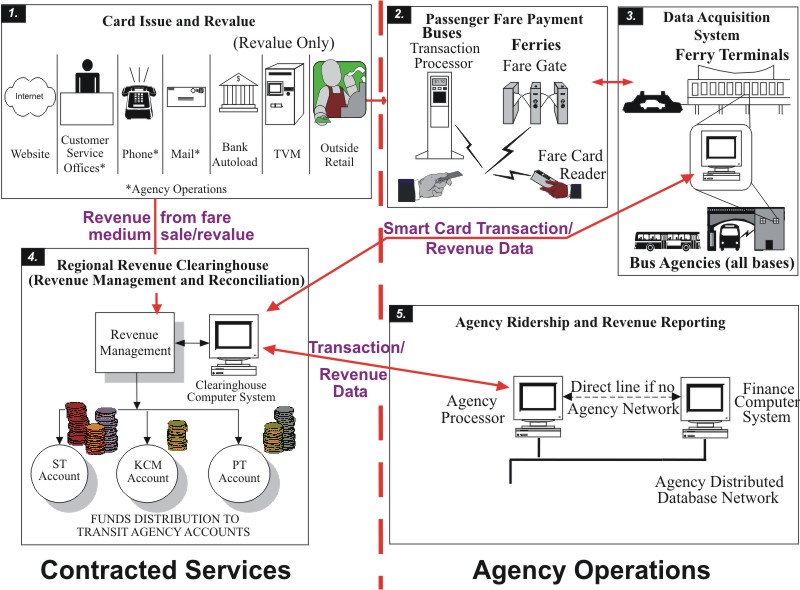

Figure 5 shows the RFC centralized operating concept overview, which illustrates how funds will flow into the system through the revenue clearinghouse and fiscal agent and, ultimately, into transit agency accounts. The RFC system will offer several outlets for customers wishing to purchase regional fare cards. Fare cards will be issued and revalued through the project website, at agency customer service offices, by phone, and by mail. The region’s extensive network of employers, schools and other institutions that subsidize passes will also handle the distribution of a significant number of cards. Customers may also add value to their card at selected retail outlets, at Sound Transit (ST) ticket vending machines, or may automatically revalue periodically based on a predetermined schedule or when the card balance drops below a specified level. Lost, stolen, or damaged cards can be easily replaced without losing value, provided that the customer registers their card with the program. For example, when replacing a lost card, the lost card is invalidated and the balance of the original card is transferred to the replacement card.

The RFC system will use contactless microprocessor electronic smart cards to automatically calculate fares due and initiate passenger payments. The partner agencies expect that following full deployment, the regional fare card and physical cash will serve as the primary forms of fare media within the region. RFC Partners estimate that they will issue 400,000 smart cards upon the commencement of revenue operations.

Figure 5. RFC Centralized Operating Concept Overview

Figure 5 shows that as partner transit agencies collect fares (e-purse reloads, pass sales, etc.) and the vendor tracks the services provided by the various agencies, each day a settlement will occur and the net of the value of the services minus revenue collected will be attributed to each partner agency. Thus, the RFC system is designed to allow transaction data to be uploaded nightly when vehicles are re-fueling or traveling on transit agency property. At these points of contact, data will be transmitted wirelessly between the on-board fare transaction processors (OBFTP) and the data acquisition system. In turn, the data will be pulled into the revenue clearinghouse. That night, a report will be produced showing a net settlement. Before the conclusion of the next day, an automated clearinghouse (ACH) report will be filed and funds transferred. Thus, the process is extremely timely and settlements occur daily with funds transferred within 48 hours of revenue generation. While this daily reconciliation process applies for the e-purse system, revenue from the sale of passes will be reconciled monthly.

This section of the report examines some of the more relevant financial issues dealt with by the partner agencies, and includes issues overviews, resolutions reached, problems faced when determining the best approach for dealing with an issue and other relevant matters. The section explores the issues in relation to three of the stages outlined in the centralized operating concept overview: card issue and revalue, passenger fare payment and the revenue clearinghouse and revenue allocation. As was the case in the development of business rules related to fares, the dynamics of multiple partner agencies and the ethos of consensus were central in the financial business rules established by the partner agencies.

8.3.1 Card Issue and Revalue

The technological capabilities of the RFC system create marketing and potentially revenue generating opportunities for the regional partners. The partner agencies recognized early on in the development process that the smart card could be designed in a manner to enable third party retailers to maintain a position on the smart card because they allow up to four applications. The partner agencies envisioned a future system whereby retailers or the partners could sell the card to their customers who would in turn use it to both purchase goods and services from the retailer and pay fares on the regional transit system. However, the Joint Board directed early on that the primary mission was to develop the transit application and design a system that best served the agencies’ business requirements. All non-transit applications would only be considered following Full System Acceptance.

A system such as the one described above was theoretically desirable in that it could be used as a marketing tool or a revenue generator if, for example, the partner agencies charged a licensing fee for the transit application. The cards could also be used in order to access buildings at major area employers and academic institutions, such as Microsoft, Boeing or the University of Washington.

Due to concerns with banking regulations that relate to the management of public funds maintained in banks in the State of Washington, an issue arises with regard to a public transit agency or another private entity that would manage the e-purse. There is also some concern expressed by the Finance SAAT that multiple entries on a card may take several additional seconds to process, producing a wait time that could cause problems for users. If, for example, the transit application were moved into the fourth position, it would potentially slow down the boarding process as the OBFTPs work sequentially through the applications to identify the e-purse account. Thus potential participants, including the transit agencies, would want to be in the first position (of four possible on the electronic card chip) so that their application is handled rapidly. However, the concept of a separate open e-purse managed by another entity (e.g. a card association), or the transit application residing on another entity’s card is still an option for future consideration.

Assuming the technical issues could be resolved, there is still the matter of complying with public funds depository rules within the State of Washington. At this time, the partners have expressed an unwillingness to act in the same manner as a private bank. The questions that are of central importance to this issue include:

- How would the partner agencies handle the commingling of public and private funds?

- Would these funds flow through the revenue clearinghouse?

- Would State auditors allow this sort of arrangement?

- How would the agencies maintain financial controls?

- Do State banking laws preclude this sort of activity?

The partners chose to move toward the closed electronic purse path. However, the system has been designed to reconsider the option at a later point in time after these issues have been resolved. The flexibility is there in the smart card and the private partner alternative remains an option that has yet to be fully explored.

Escheatment laws were also problematic from the standpoint of the partner agencies. The State of Washington requires that after two years, any unclaimed property revert to the State with the property available to be claimed later by the citizen provided the person is informed of the unclaimed property and can validate his or her claim to it. As it relates to the RFC Project, the e‑purse was an issue. Would the partners be required to pass along unused portions of e-purse accounts following two years of inactivity? Such a requirement would introduce additional complexity in the revenue clearinghouse and would require that these funds revert to the State’s general fund, along with relevant information that could be used to locate the customer. The partners noted that under current law, the Washington State Lottery receives an exemption from the escheatment laws related to unclaimed awards. In turn, the region’s transit agencies have considered seeking a legislative remedy to this issue.

8.3.2 Passenger Fare Payment

Under the RFC system, passengers are presented with numerous alternatives for purchasing and revaluing cards. Payments can be made over the Internet, at customer service offices, by phone, by mail, at retail outlets, at ticket vending machines and can be done automatically through bank autoloads. Under the autoload option, cards would be revalued to pre-determined amounts (i.e., $100) once the e-purse balance drops below a specified value (i.e., $5). Payment may take the form of cash, debit or credit card or check. Also, autoloads of pass products can be triggered by date (e.g., the 25th of the month autoload of the next month’s pass).

What happens if the partner agency receives a Not Sufficient Funds (NSF) check? In the past when a transit agency issued a pass and received an NSF check, the agency absorbed the loss or attempted to notify the customer and recover the payment, though the amount of the NSF check rarely warranted an aggressive collection approach. Under the RFC system, NSF information will be stored in the revenue clearinghouse. From this, a bad check list will be created, thus restricting the ability of the passenger to write future checks. The agencies considered blocking the use of the smart card purchased with the NSF check; however, this is problematic because the passenger could have an existing balance previously obtained with cash or through another valid payment method. To block the card would be to deny the person the opportunity to access a valid e-purse balance. In order to reduce the risk associated with NSF checks, the partner agencies have established business rules to limit e-purse values, build in the ability to block the card, limit period passes to 30 days and identify passengers with a history of writing NSF checks.

An additional complexity associated with the technology that has presented customer service problems to the agencies relates to the interaction between the “back-office” system that handles all transaction data, reporting and revenue reconciliation and the OBFTPs. When passengers revalue their card at a retail outlet, ticket vending machine or customer service office, the data are immediately stored on the smart card. However, because the data acquisition systems must communicate with the OBFTPs in order to share transaction data, remote revaluation of the smart card through phone and Internet transactions result in a one-day delay between payment and service availability. That is, a phone payment must be communicated to the OBFTPs when they transmit data to the data acquisition system, and must then be communicated to the smart card before the enhanced balance may be accessed. This requires self-monitoring on the part of the passenger, which is difficult and could lead to customer satisfaction issues. This issue has not been resolved due to technological limitations.

8.3.3 Regional Revenue Clearinghouse and Revenue Allocation

In the State of Washington, public funds must be held in government-controlled bank accounts within banks located in Washington. Thus, all RFC Project revenue allocation procedures were designed with State rules related to the handling of public funds in mind, which means that the revenue clearinghouse, which represents a vendor-operated technology, serves as a conduit through which settlements are cleared. At all times, revenue generated by the system must be deposited in bank accounts managed by a government agency. In this case, the partners rely on Sound Transit (ST) as the Fiscal Agent. As the fiscal agent, ST is responsible for managing regional bank accounts for the RFC system. Each agency establishes its own bank accounts and authorizes the fund movement in and out of those specific accounts.

Acting as the Fiscal Agent generates both financial opportunities and risks to ST. In response, the partner agencies have designed certain business rules to minimize the financial gains (e.g., interest on revenue from unused passes) and mitigate ST risk exposure. For example, the system is designed in a manner that ensures that the fiscal agent must always be made whole. If the fiscal agent were not made whole each day, there would be great financial risk to both the fiscal agent and the partner agencies. That is, there could potentially be an un-booked liability not shown on an agency’s balance sheet. In the event that the liability was discovered later, an agency could be asked to recover a substantial sum for which no budgeting would have been made.

How could the fiscal agent experience a shortfall? Retailers, for example, sell passes every day but some transmit the revenue from these sales on a weekly basis. In the event that agents sell the passes on Monday but funds are not collected until Friday, the agencies may be due funds as the pass is used throughout the week but the fiscal agent would not have received any revenue from the third party agent. To address this sort of financial liability to ST, the partner agencies are collectively funding a $200,000 float account in order to keep the fiscal agent whole.

With respect to financial gains, partner agencies expressed concern that they would lose revenue associated with the float, or interest earned when funds rest in a revenue account, and that these revenues would accrue to ST, acting in its role as the fiscal agent. How could the interest accrue to the fiscal agent? If a passenger replenishes his or her e-purse electronically, funds will flow from the passenger’s bank account into an account managed by the fiscal agent. As the e-purse is drawn upon, agencies supplying services will receive fares from the fiscal agent. The unused portion of the e-purse balance will be resting in a revenue-generating account controlled by ST. In order to minimize float and expedite the transmission of revenue, the partner agencies designed the net settlement approach with its swift 48-hour funding period. Further, the partner agencies have agreed on a quarterly distribution of interest revenue based on the operating and maintenance shares for each partner agency shown in Table 7 in Section 8.5.1.

While the Joint Board has required the partner agencies to limit the scope of their activities in the RFC Project to focus on the implementation of a viable smart card for public transportation applications, there is future promise for this technology to support other financial applications of value to the agencies and their customers.

Lesson: Take Advantage of the Technology to Enhance Revenue and

Improve Management of Financial Operations

- Consider allowing third party retailers to maintain a position on the smart card and use the card for both public transit and retail purchases. Weigh the marketing benefits against the financial requirements and technological barriers associated with third party integration.

- Where feasible, integrate the card with existing on-site security systems of large institutional customers. The smart card technology could be used to access buildings at major area employers.

- Present passengers with numerous alternatives for purchasing and revaluing cards – e.g., phone, mail, retail outlets, ticket vending machines. Minimize the time between when the payment is made and when the card is revalued and can be used on-board transit vehicles.

- Use the smart card technology to limit the impact of NSF checks.

- Consider using the smart card technology to generate data for financial reports, improve passenger count estimates and better understand the market in each jurisdiction.

8.4 Fares

The cooperative establishment of a set of regional fare policies has proven to be a daunting task for the agencies participating in the regional fare coordination project. The automation of regional fare transactions is complicated by differences in agency policies relating to discount rates on monthly passes and proposed e-purse applications, transfer policies and revenue reconciliation, fare integration principles, fare standardization, treatment of institutional accounts and discounts for elderly and youth passengers. Agency agendas are shaped by historic practices, customer demographics and other elements that drive fare policies. While each agency recognizes the importance of a comprehensive and simple regional fare policy from a customer service perspective, each is reluctant to abandon local autonomy when it comes to setting fare policy. Furthermore, each agency is keenly aware of the financial implications of changes to existing fare structures. With this in mind, the agencies formed a Fare SAAT to deal with the many complex fare-related issues facing them. This section of the report examines some the more significant issues dealt with by the Fare SAAT.

8.4.1 Integrated versus Coordinated Fare Structure

The primary challenge to designing a multiagency fare system or framework that meets the needs of all seven participating agencies has been the strong desire among the partners to maintain autonomy with respect to local fare policy. In broad terms, multiagency fare management programs generally take one of two forms:

- Integrated fare structures that operate on a single standard when calculating fares, as applied consistently across all participating agencies.[42] Under this structure, travelers pay fares according to a consistently applied system of zones, discounts and rate policies applied ubiquitously within the region served by the regional fare management program. Examples of integrated systems can be found in Phoenix, Arizona (Valley Metro) and Hong Kong (Octopus).

- Coordinated fare structures enable passengers to use a single fare medium but allow partner agencies to retain autonomy in setting fare policies. Thus, passengers enjoy the convenience of using a single fare card but may encounter complex fare structures with features (e.g., discount rates on fare card transactions, transfer credits) that vary from one agency to the next. Examples of coordinated fare structures can be found in Ventura County, California (Passport) and the San Francisco Bay Area of California (TransLinkâ).

The RFC Project partner agencies have adopted a framework for coordination of existing agency fare structures. The preference for the coordinated framework is due in part to the wide variance among the partner agencies when it comes to fare policy objectives. These policy differences are related to differences in the customer base served by each agency and their overall mission. In addition to using the single fare medium (the smart card), the partner agencies are sharing revenue from transfer discounts, and they are allocating revenue from pass products that are valid on six of the seven agencies’ systems (all but WSF).

A coordinated framework allows for more local control of certain fare policies, which is desirable to the agencies participating in the RFC Project. Local autonomy, however, results in technological and fare structure complications that can drive up programming costs and negatively affect customer service. The lack of uniform fare policies could potentially result in complications that weaken customer acceptance of the technology. For example, inconsistent discount rates would result in customers being charged different fares for inbound and outbound trips. Furthermore, the amount of revenue allocated to each agency would also differ. To illustrate this point, consider the following example.

Example:

A rider takes a morning trip on a KCM bus with a $1.50 fare and transfers to an ST bus with a $2 fare and then returns later that night taking the same buses in the reverse order. These calculations examine the morning trip.[43]

- Assume the discount for KCM is 10% and the ST discount is 15%.

- Assume that fares are allocated based on a purse contribution value (fare – discounts applied).

- The total fares paid from the purse would be $1.35 ($1.50 – 10% discount) + $0.55 ($2 - $1.35 credit from first fare – 15% discount on remaining fare) = $1.90.

- Total purse contribution value (total fare – discounts applied) = $1.35 (KCM) + $1.90 (ST) = $3.25.

- KCM share of revenues = $1.35 / $3.25 * $1.90 = $0.79.

- ST share of revenues = $1.90 / $3.25 = $1.11.

If both KCM and ST offered an identical 10 percent discount, the KCM share would increase to $0.80 while the ST share would be $1.15. Thus, in this instance, KCM would be partially subsidizing the higher ST discount rate.

On the return trip, the total fares from the purse would be equal to $1.70 because the rider would receive credit for the larger 15 percent discount on the first leg of the journey, the ST share of purse revenue would be $0.90 and the KCM share would be $.80. In the absence of the discount rate differential, the ST share of purse revenue would be $0.92 and the KCM share would be $0.82. Once again, KCM would be subsidizing the higher ST discount rate.

8.4.2 Transfers and Revenue Reconciliation

The Fare SAAT has dealt with numerous issues relating to the treatment of interjurisdictional transfers. In addition to decisions concerning how to attribute revenue between agencies, there are issues relating to the transfer period, discount values, the basis of revenue reconciliation, treatment of cash and potential transfer surcharges. Each of these issues made it difficult to establish a regional fare policy. However, the representatives of the seven partner agencies serving on the Fare SAAT have worked cooperatively to establish a set of recommended general policies dealing with these issues, including those outlined below:

- With respect to transfer periods, there should be a regional one (current recommendation of 2 hours) but the system should be designed to allow the transfer period to be changed at a later date.

- The partners are considering a $0.25 transfer surcharge and the system should be designed in a manner to accommodate such a charge.

- Cash paid during multiagency trips will be retained by the collecting agency, and not included in the revenue reconciliation process. The decision to recognize cash boardings when issuing intersystem transfers will be at the discretion of the local transit agency.

- Revenue reconciliation will be based on the proportion of the value of services provided, as based on the cash value of the trips taken.

The last point is significant. Under the Puget Pass system, revenue was shared among agencies based on the estimated total number of boardings and the average fares per boarding as determined through survey data. Under the RFC system, the value of each trip allocated to each agency will be determined on a cash fare basis, which is based on the full fare of each leg of a trip, and on actual trips as recorded by the fare transaction processors. To illustrate this adjustment in policy, consider the following example.

Example 1: Puget Pass[44]

A rider uses Puget Pass to pay a $1.50 fare on a KCM bus. She then transfers to a CT bus with a $3 fare and finally transfers to a bus on a local CT route with a $1 fare. The fare would be divided under the Puget Pass system as follows:

- The KCM average fare per boarding is $0.7747 and the CT average fare per boarding is $1.39.

- KCM receives $0.7747 for their leg of the trip.

- CT receives $1.3957 * 2 (2 boardings) = $2.7914

- The rider pays $1.50 on KCM and $2 on CT for a total of $3.50.

- Sound Transit fare integration fund provides $0.06661.

Example 2: RFC System[45]

Under the RFC Project, the money would be divided based on the cash value of each trip as follows:

- The rider receives a 10% percent discount for using the smart card.

- The cash value of the services provided by KCM is $1.35 ($1.50 - $0.15 discount).

- The cash value of the services provided by CT is $2.70 ($3 - $0.30 discount) because the second leg is considered a free intrasystem transfer.

- The total cash equivalent value of the services provided by KCM and CT is $4.05.

- The KCM share is $1.35 / $4.05 = 33% * $2.70 (fare paid) = $0.90.

- The CT share is $2.70 / $4.05 = 67% * $2.70 (fare paid) = $1.80.

- There are no payments from the fare integration fund.

In keeping with the coordinated framework approach, the partner agencies agree that the RFC system should be flexible enough to accommodate changes in fare policy after implementation and in policies that vary between agencies.

8.4.3 E-Purse Incentive Programs

A recent TCRP publication that considers the development of a recommended standard for automated fare collection notes that “A program’s inability to offer patrons financial incentive to use multiagency instruments can cause such undertakings to fail because of a lack of customer interest.”[46] Thus, the partner agencies have considered several incentives designed to induce participation in the RFC Project. The motivations for offering discounts differ significantly between the partner agencies. For example, CT argues for less discounting due to their limited capacity and their focus on recovering revenue. On the other hand, fare integration was identified as a long-term goal in Sound Move, Sound Transit’s long-range plan. Also, ST is motivated because, under the Puget Pass system, it subsidizes participation on the part of local transit agencies through the fare integration fund.

The partner agencies have considered several potential incentive programs:

- Loading money bonus where a customer would receive additional credit when loading a card (e.g., they pay $20 and receive a $21 credit).

- Loading product bonus where the customer would receive a product when they load a card (e.g., they load $100 and receive a free day pass on Sounder Rail).

- E-purse trip discounts where a customer pays a discounted fare (e.g., $1.50 fare reduced to $1.35 due to 10% discount).

- Free rides bonus where a customer gets a free ride when they have purchased a pre-determined number of trips (e.g., buy 10 trips get the 11th free).

- E-purse caps where a customer is not charged to ride after a pre-determined ceiling is reached (e.g., customer can be charged a maximum of $5 per day by partner agencies).

- Special promotions where a customer would receive special discounts at a specific time or at a specific location, as determined by each partner agency.

The majority of these incentive programs have been rejected due to revenue reconciliation issues, issues related to refunds, technological barriers and transaction time issues. Since many of these reasons for concept rejection are tied to revenue reconciliation and technology barriers, to a certain extent the design of the RFC system can drive fare policy. Thus, system design and the ability to offer incentives are interlinked. The e-purse discount was selected as the preferred option by both the Finance and Fare SAATs.

8.4.4 Regional Fare Categories

The regional fare policy requires standard passenger definitions in order to assign discounts and other subsidies to certain passenger groups. Historically, the rider categories have been inconsistent between agencies. However, the Fare SAAT has recommended the following fare categories:

- Children under 6 ride free

- Youths are ages 6-18

- Adults are ages 19-64

- Seniors are ages 65 and over

Once again, partner agencies have expressed the desire to retain autonomy with respect to defining these categories on local routes. For example, ET defines a senior citizen as 62 years of age and beyond, and KT is interested in maintaining the ability to offer discounts to low-income riders.

8.4.5 Fare Integration

To the extent that the smart card system applies overly complicated fare schedules that are not easily understandable from the standpoint of the consumer, this may create an untenable position where consumers are reluctant to convert to the new system, argue with drivers concerning fare policies and experience less satisfaction with the local services. Therefore, many of the partner agencies view the RFC Project as an opportunity to simplify fare structures. One partner agency (CT) expressed a strong interest in simplifying the fare structure and argued that the KCM fare schedule was too complicated, making it difficult for the other agencies to design a comprehensive, understandable fare structure. While some agencies have been more reluctant to refine fare schedules and instead favor the replication of the current fare network, the partner agencies recognize the importance of reaching consensus on the simplification and integration of their fare structures.

Lesson: Assess the Tradeoffs between Local Autonomy, Customer Service

and Other Financial Considerations When Designing a Fare Structure

- The desire for a particular fare structure is driven by the partner agencies’ characteristics, operating context and fare policy objectives.

- Allow each partner a voice in determining the fare policy adopted for the region.

- Establish a coordinated framework to effectively accommodate differences in fare structures and discount policies across participating agencies.

- Local autonomy, which is highly valued by the partner agencies, can result in technological and fare structure complications that drive up programming costs and negatively affect customer service.

- Minimize technological and fare structure complications to the extent possible because these factors can have a significant impact on customer service and technology acceptance.

- Monetize the impacts of various fare policies on the partner agencies in order to support increased equity.

8.5 Project Finance

The development of a viable project finance plan in a multi-jurisdictional setting has proven difficult and has required substantial flexibility on the part of the partner agencies. Innovation through partner subsidies, private donations, grant sharing and cost-sharing has resulted in a finance plan that includes a variety of funding sources. Even as the partners have worked together to develop a finance plan agreed to by all parties, unforeseen external factors, such as the voter-approved Motor Vehicle Excise Tax (MVET) repeal, have presented challenges that have nearly derailed the RFC program. Through voter-approved sales tax increases meant to replace the funding lost to the MVET repeal and other remedial measures, these challenges have been addressed, and the RFC finance plan has slowly taken shape. This section first presents an overview of the RFC Project costs (capital, operations and maintenance) and sources of funds supporting the RFC Project and then examines the evolution of the project finance plan as the partner agencies have worked cooperatively to overcome the significant financial challenges to project implementation.

8.5.1 Project Budget and Revenues

The total capital costs of the RFC Project are estimated at $42.1 million (nominal),[47] paid out during the 2003-2006 timeframe, as shown in Table 4. This estimate includes all vendor contract cost components, including equipment, equipment installation, fare cards, integration and project management as well as other RFC Project administration costs, including sales tax, contingency fund, and project management team (Regional Team) costs. This estimate includes only regionally shared items in the RFC Project capital budget and does not include an estimated $6.4 million in individual agency implementation costs.

The cost shares are allocated among the seven participating agencies based on the proportional share of total RFC Project equipment purchased by each agency. The cost shares by partner agency are presented in Table 5.[48] The vendor contract accounts for roughly $31 million of the $42 million in capital costs. Thus, other implementation costs – e.g., joint agency project management staff, technical consultant support, sales tax, contingency fund, dispute resolution board, intellectual property management, project evaluation and customer marketing and information – that are not tied to equipment purchases but are included in the capital finance plan are similarly allocated based on relative shares of equipment purchases. Though this method was viewed as intuitive by the partner agencies and was not a particularly contentious issue in the development of the regional finance plan, the collective nature of applying the “equipment purchases” formula to the regional implementation costs does require financial accountability and accurate budgeting of these costs. One of the partner agencies expressed a need for greater financial accountability of their regionally shared costs and felt that partner agencies should have more control and involvement in RFC Project expenditures. A partner agency also noted that agency expenses are rising against a budget that hasn’t changed.

| Cost Categories |

Cost ($Nominal) |

|---|---|

Equipment purchases[49] |

$7,424,663 |

Installation costs |

$326,728 |

Fare card costs |

$761,006 |

Integration costs[50] |

$511,843 |

Reports |

$563,812 |

Implementation costs[51] |

$12,694,940 |

Project management: performance security |

$8,016,013 |

Training costs[52] |

$716,375 |

Regional project management |

$1,029,000 |

Regional technical consultant |

$525,000 |

Sales tax @ 8.8% |

$2,729,353 |

Contingency fund at 20% of vendor contract value |

$6,203,076 |

Dispute resolution board |

$122,100 |

Software escrow account |

$99,000 |

Project evaluation[53] |

$75,000 |

Project marketing |

$300,000 |

Sound Transit consultant fee |

$27,100 |

Total Capital and Administration Costs |

$42,125,009 |

| Partner |

KCM |

CT |

ST |

PT |

KT |

WSF |

ET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Equipment Share |

55.2% |

11.6% |

10.7% |

8.6% |

5.9% |

5.3% |

2.9% |

Total operations and maintenance costs over a 10-year time horizon are shown in Table 6 and are estimated at $32.8 million (nominal) and include depot maintenance, software maintenance, customer service, card procurement and distribution, and fare card management.[54] Operations and maintenance cost shares (Table 7) are distributed among the participating agencies based on a ridership formula. For example, KCM accounts for 70.7 percent of total transit ridership in the region. Thus, KCM will be initially responsible for paying 70.7 percent of total RFC system operations and maintenance costs. In addition, King County provides central services, including card procurement, local card warehousing and distribution and new card order fulfillment, and is reimbursed based on the ridership formula.

| Cost Categories |

Cost ($Nominal) |

|---|---|

Depot maintenance |

$455,993 |

On-call maintenance |

$604,019 |

Technical support maintenance |

$758,053 |

Software maintenance |

$3,809,400 |

Customer service |

$2,846,783 |

Institutional programs[56] |

$1,838,065 |

Card procurement and distribution |

$1,495,014 |

Fare card management |

$843,796 |

Clearinghouse services[57] |

$11,188,757 |

Financial management |

$1,541,676 |

Network management |

$1,812,664 |

Revalue network support |

$1,549,792 |

New card fulfillment |

$3,820,035 |

Additional card procurement, inventory, warehousing and distribution functions |

$254,815 |

Invoicing and funds collection |

TBD |

Total O&M Costs |

$32,818,861 |

At such time as the system is determined to be at “steady state” operations (estimated one year), the operations cost-sharing formula will be based on actual transaction data. The operations and maintenance costs have been incorporated into the vendor contract, and extend out 10 years following system deployment. The partners viewed this long-term commitment on the part of ERG to the RFC system as an important component of the vendor contract.

| Partner |

KCM |

PT |

ST |

CT |

WSF |

KT |

ET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ridership-based Shares |

70.7% |

9.1% |

7.6% |

5.9% |

2.8% |

2.6% |

1.4% |

The RFC Project finance plan includes federal, local and private sources (Table 8). As of April 2003, the RFC Project had received 12 federal grants, a donation from the Boeing Company and an appropriation from ST’s technology fund. As presented in Table 8, total regional revenues from these sources total $20.2 million, with a total match requirement of an additional $7.2 million.[59] The balance of capital funding is expected to be provided through partner agencies’ capital budgets and an appropriation from the ST Fare Integration Fund.[60]

| Revenue Source |

Match Requirement |

Total |

Total Match Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

Federal Section |

20% |

$9,575,958 |

$2,393,990 |

Congestion Mitigation and Air |

13.5% |

$2,686,000 |

$419,202 |

ITS Earmarks |

50% |

$4,421,941 |

$4,421,941 |

Boeing Donation |

N/A |

$500,000 |

0 |

ST Technology |

N/A |

$3,000,000 |

0 |

Total |

|

$20,183,899 |

$7,235,133 |

The RFC Project was awarded numerous regional grants designed to assist the project. Rather than allocating individual grants to partner agencies, the RFC partners agreed to disburse grants to agencies according to the capital purchases shares presented in Table 5. Grants are disbursed based on the equipment purchases formula, thus encouraging participation. To the extent that a partner agency expands participation in the RFC Program, both its responsibility for project costs as well as its share of total grant revenue would grow commensurate with its participation.

8.5.2 Financial Barriers to Project Development

In 1999, Washington voters dealt a blow to the RFC Project finance plan when they repealed the state’s motor vehicle excise tax (MVET) of 2.2 percent and replaced it with a flat $30 annual licensing fee on private cars and trucks. In the 1999 – 2001 biennium alone, the MVET was expected to generate roughly $1.5 billion in revenues, with 29 percent dedicated to local transit districts.[61] Prior to its repeal, MVET revenue accounted for approximately 30 percent of King County Metro’s operating funds.

In response to the passage of I-695 (the MVET repeal), the Washington State Legislature passed Senate Bill 6856, which gave local governments the authority to raise sales taxes dedicated to public transit purposes up to 0.9 percent with voter approval. The legislature also provided one-time funding of $220 million in order to temporarily maintain current service levels while local agencies searched for new sources of funding.

Voters in King, Snohomish, Pierce and Kitsap counties have since approved separate increases in local sales taxes in order to close the gap created by the MVET repeal and restore public transit services. In November of 2000, King County voters approved a transit sales tax of 0.2 percent. The tax was implemented in April 2001 and KCM received the additional revenue beginning in June 2001. In May 2001, Kitsap County voters approved a 0.3 percent increase in local sales taxes for public transit. The Kitsap sales tax increase replaced approximately 75 percent of the revenue lost to I-695. In September 2001, Snohomish County voters narrowly approved a 0.3 percent increase in local sales taxes for public transit purposes. Finally, in November 2001, Pierce County voters approved a 0.3 percent transit sales tax on all retail sales within the county’s PTBA.

Even with the passage of the sales tax measures, several partner agencies found it difficult to make the business case to participate in the RFC Project. Sound Transit played a significant role in assisting these agencies in overcoming financial barriers to joining the RFC Project.

Under Puget Pass, a precursor to the RFC system, Sound Transit settled receipts and distributed them to partner agencies based on passenger estimates and average fares per boarding as established by surveys conducted once every two years. Puget Pass was viewed as an interim solution until the RFC system could be implemented. The Puget Pass system subsidized riders by allowing them to pay a single fare when traveling through multiple jurisdictions. However, this practice led to revenue shortfalls to local transit agencies. Sound Transit, in turn, used funds out of its fare integration fund in order to offset a portion of these fare box shortfalls in the Puget Pass system.

Sound Transit has continued its financial commitment to local transit agencies in an effort to get them on-board with the regional fare card project. Sound Transit will fund a portion of the RFC program capital costs not covered by regional grants for Everett Transit, Pierce Transit, Community Transit and King County Metro, and will pay part of the first two years’ operating costs for these agencies. The contribution to each of the partner agencies has been established through a series of agreements, which collectively place a cap on the ST contribution. In addition, Sound Transit has contributed $3 million to the RFC Project out of its technology fund. Sound Transit’s commitment to the RFC Project and the subsidy it has provided to its partners was viewed by numerous agency representatives interviewed for this study as an important factor when making the decision to participate or drop out of the project.

8.5.3 Adding and Removing Partner Agencies

The partner agencies understand that there will be further applications of the smart card system (e.g., Olympia’s Intercity Transit, the Seattle Monorail, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, Seattle’s municipal parking operations). Thus, the Interlocal Agreement considers the addition and withdrawal of parties from the RFC Project. The ILA establishes that the Joint Board must approve the terms and conditions of any addition or withdrawal from the agreement but stipulates that any new party joining the project be required to:

- pay for its equipment and any costs required to accommodate the installation and use of the equipment, and

- pay a charge to recover costs associated with the planning, design and implementation costs incurred by the RFC partner agencies.

Lesson: Build Flexibility and Creativity into the Project Finance Plan

- Build a finance plan that includes federal, state, local and private sources. Projects of regional significance are rarely financed from a single revenue source.

- Seek partnership opportunities with private partners who benefit from the technology.

- Remain flexible in dealing with the numerous financial pitfalls and issues that arise during project development.

- Consider disbursing grant funds according to capital cost shares in order to encourage participation.

- Lead agencies and partners interested in advancing the project should consider providing financial assistance (e.g., loans, fare recovery subsidies, grant sharing) to smaller or less interested partners who otherwise might not choose to participate, but whose inclusion would enhance the system.

- Recognize that a project with significant capital costs will not be funded overnight. Rather, a project’s finance plan is built slowly over time as capital budgets are assessed and grant opportunities and partnering arrangements are explored.

- Recognize that initial cost estimates are rarely accurate and that project delays translate into higher capital costs.

- Establish rules for opting in and out of the program in order to encourage system expansion, which enhances visibility and program effectiveness. Recognize that the original project sponsors made a significant up-front investment in the project in system design and implementation and that agencies that later opt into the project should pay a charge to cover some of these costs.

The capital and O&M formulas established in the ILA were viewed by representatives of the Finance SAAT as appropriate for capturing costs generated by future partners. However, the second charge outlined in the ILA was also viewed as necessary in order to recover part of the sunk costs of the project paid by the originating agencies. Establishing a protocol for admitting and removing partner agencies was viewed as an important element of the agreement, one that will lay the foundation for future expansion.

8.6 Making the Business Case

The importance that each partner agency places on the financial element of the business case varies significantly. In some instances, partner agencies have constructed business cases and carefully assessed the potential benefits and impacts of the RFC Project. In others, the agencies have performed only cursory financial analyses and concluded that the project would not generate a positive return on investment. In each case where a partner agency was unable to demonstrate financial benefits, greater emphasis was placed on improving customer service, enhancing connectivity and promoting the region’s economy. Thus, intangible or qualitative benefits were viewed as important in many cases as the more quantifiable financial ones.

For some partner agencies, there was an overriding need to make the business case, either due to budget pressures or financial accountability standards. For example, KCM has set a goal of recovering their capital costs of the RFC program within an estimated three-year payback period, while other agencies felt they may never be able to fully recover their costs. Financial accountability is viewed in similar terms at WSF. The WSF system represents the only state-owned and -operated partner agency. Since the repeal of the MVET, the pressure has mounted on WSF to reduce its operating subsidy. The Washington Legislative Joint Task Force on Ferries has set a 20 percent operating subsidy goal for the WSF system and the Blue Ribbon Commission on Transportation recommended that within 20 years, the WSF system should achieve a 90 percent recovery ratio.[62] In 2004, fares and other operating revenues were $128.9 million compared to $164.1 million in operating costs (78.5 percent recovery ratio). Thus, WSF has almost achieved its legislative goal and is hesitant to increase operating costs without an expectation of operational efficiencies or revenue creation.

This section of the report examines the financial benefits outlined by partner agencies when making the business case for the RFC Project. These benefits are grouped by category, including operational efficiencies, safety benefits and expanded revenue sources. This report does not attempt to quantify these benefit elements.

8.6.1 Operational Efficiencies and Productivity

Partner agencies anticipate a number of operational efficiencies as a direct result of the regional fare card system that will reduce their administrative burden and enhance productivity. These efficiencies are expected to translate into direct and indirect cost savings and enhanced operations. For example, partner agencies anticipate a reduction in the costs of manufacturing, processing and distributing fare media. Administrative cost reductions are also anticipated, including those related to the monthly management of organizational accounts.

Perhaps the greatest hurdle to multi-agency fare and service initiatives in the pre-smart card world is the lack of reliable data on which to base business rules (cost and revenue sharing rules). Though the agencies have entered into some regional fare initiatives (e.g., Puget Pass), they have traditionally developed business rules based on survey data. The smart card system would generate actual transactional data that will greatly support the development of such business rules, and thus will aid in the development of truly integrated regional fare products.

A large portion (more than 80 percent) of King County’s transit passes are purchased and administered by institutions – corporations and organizations – that also subsidize the value of the transit fare for their employees. Private sector businesses employ a variety of mechanisms to encourage and support their employees to use the system, and they work closely with the public transportation agencies to do that. This is made more difficult by the lack of underlying integration across the system components and by the lack of a single fare card that can serve both public transportation needs as well as offer businesses and travelers additional functionality (i.e., the ability to use the card for non-transportation purposes and transactions). The regional fare card project will help the participating agencies serve their business client base more effectively in two ways:

- The regional fare card project would significantly reduce the administrative and logistic burden of fare distribution on the organizations operating such programs. Automatic revaluing would replace a periodic administration of fare cards.

- In many cases, transportation agencies sign customized deals with organizational accounts—contracts that provide the organization with reduced costs for transit products in exchange for other travel policies implemented by the organization (such as restraining a parking benefit). Currently, for example, a visitor card is being discussed with the Convention Bureau that would offer visitors access to both transportation and convention facilities and functions. Negotiating these kinds of contracts is significantly hampered by the lack of reliable data that can be used to analyze the impact of a deal on overall transit use patterns. The regional fare card project will supply much of the data that the partner organizations need to develop effective contracts.

Finally, the regional fare card system is expected to greatly reduce the volume of cash processed by partner agencies. Reducing the cash volumes handled by the transit agencies will result in the elimination of cash counting and handling positions, thus reducing overhead costs to each agency.

Productivity enhancements are also anticipated. The proliferation of multiple fare systems and on-board hardware systems reduce operational efficiency and increase costs. For example, there are currently over 300 different types of fare media in use in the region. In addition, buses operated by each agency have multiple technological components (e.g., fare boxes and radio systems) that need to be switched on and made operational for effective revenue service. Currently the driver needs to log on to each component separately. Often drivers make mistakes, increasing the time and effort required for log-on. Sometimes they are unable to log on properly to some sub-systems, with potential negative impacts on safety and on revenue (they may use the wrong fare setting if they log on incorrectly). As part of the regional fare card system, the agencies will be able to operate multiple on-board devices using a single easy-to-use unit. The participating agencies expect this development to be a major operational advantage. Further, use of the on-board fare transaction processors and contactless card will lead to a decrease in passenger boarding time and increased operating speeds.

8.6.2 Safety Benefits

Safety is a significant concern of transit agencies. In 2003, incidents involving transit vehicles and facilities in the U.S. resulted in 173 fatalities. These incidents involved passengers, transit facility occupants, transit agency employees, other workers, trespassers and other individuals. It is hoped that widespread use of the fare card may reduce the number of driver—passenger fare disputes.

An integrated on-board system that allows drivers easily to log onto all of a bus’s component subsystems at one time could result in better communication, reduced driver distraction, and higher levels of safety. The societal cost associated with bus crashes is significant. In 2002, these costs were estimated on a per-crash basis at $32,548 (2000 dollars).[63] The average cost of a bus crash involving an incapacitating injury or fatality was estimated $323.9 thousand and $2.7 million, respectively. Thus, to the extent that the RFC system could successfully reduce the number of major incidents, the cost savings to both the participating transit agencies and society more generally could be significant.

Additional safety benefits could accrue to passengers riding the transportation systems using smart cards because they will not have to handle cash to pay fares in public.

8.6.3 Expanded Revenue

The regional fare card system is expected to increase revenue from a number of sources, including the reduction of fare theft, reduced fare evasion, expanded ridership and float management. These revenue sources were noted by several agency representatives during recent interviews and in a regional fare coordination feasibility study commissioned by the partner agencies completed in 1996.[64]

Fare theft is a significant issue to WSF. The Washington State Auditor has found “visible and glaring weaknesses in the ferry system’s fare collection system. ”[65] These weaknesses, which include the lack of automated systems to record the receipt of passenger and auto fares on ferries, have resulted in alleged fare theft by ticket sellers. In 2004, the Washington State Patrol arrested four WSF ticket sellers after they were observed by surveillance cameras stealing approximately $1,800 in passenger fares at WSF tollbooths. This issue is important to WSF from both a revenue and public image perspective. Washington State Ferries is currently replacing its entire fare collection system, including its point of sale terminals. The new functionality of the stored value system in combination with the automated stationary fare transaction processors will reduce cash volumes handled by ticket sellers and will greatly reduce the risk associated with theft.

The regional fare card system could also address fare evasion by reducing the number of invalid tickets, transfers and passes in circulation. Though fare evasion is considered a relatively minor issue by most of the partners, KT and ET have acknowledged that the use of outdated non-automated fare collection boxes does little to discourage fare evasion. Thus, the smart card system could also remove the ability of passengers to drop less than full fares into fare collection boxes. This source of fare evasion can lead to fare disputes, which is one of the most common sources of driver-reported incidents.

The stored value nature of the smart card and reduced reliance on cash-based transactions will accelerate the timing of transit agency revenue and result in a revenue float that the partner agencies can invest or use to reduce debt volumes. Managing the float effectively would generate new revenue for the partner agencies.

The smart card system will enhance customer service and enable riders to use a single fare medium on seven transit systems in the Central Puget Sound region. The ability to carry the single card while transferring among many systems could increase the attractiveness of the region’s transit system and enhance ridership. By making the regional transit system more accessible, some partner agency representatives believe that the smart card system will be more attractive to the casual rider traveling locally on leisure or shopping trips.

The smart card technology could also enhance sales to institutional accounts by increasing the attractiveness of employer-purchased transit passes. Employers attempting to meet Commute Trip Reduction requirements will appreciate the system’s card management capabilities and its ability to generate data at the transaction level. The detailed data generated by the system will enable employers to monitor the transit usage patterns of its employees and better manage their accounts. The one-time distribution of the cards and the ability to transfer unused portions of purchased fares between cards will reduce the administrative costs to the employers tied to card purchasing and management.

8.6.4 Business Case Conclusion

For some partner agencies, the financial case for involvement is paramount (i.e., WSF and KCM). Other agencies view the financial benefits of the regional fare card system skeptically but recognize the importance of the system in evolutionary terms moving the agencies into the 21st century and enhancing connectivity throughout the region. Furthermore, some agencies have expressed a concern that if the partner agencies were unable to establish a common fare system, the case could be made for a super agency taking over operations for the entire region. The ability to offer seamless fare systems as the communities of the Central Puget Sound region become increasingly interlinked advances the march toward regionalism.

Regional fare programs date back to the 1980s and Puget Pass continued that trend. However, Puget Pass was limited in scope. For example, the WSF system presently offers ship to shore passes but does not participate in Puget Pass, nor does KT. The regional fare card system expands the regional fare card system and is viewed by several of the partners as a continuation in the natural evolution of regionalism. There is concern that agencies and communities failing to heed the call of regionalism could encounter operational barriers, experience reduced mobility and incur negative economic consequences.

Lesson: Make the Business Case from a Broad Perspective

- Recognize that the importance that each partner agency places on the financial element of the business case varies significantly. Some agencies are required to demonstrate positive returns on investment while others are more concerned with seamless interconnections between transit providers or advancing regional partnerships.

- Take a broad view when considering the numerous operational, safety and revenue benefits to system development.

- Consider the qualitative benefits (e.g., regionalism, enhanced regional connectivity) as well as the quantitative investment benefits when making the business case.

- Remember that not all partners are likely to demonstrate positive net financial returns on investment. The majority of the partners interviewed for this study were unable to make the business case by demonstrating economic benefits that exceed the costs of deployment; however, every partner recognized the ongoing trend towards an interconnected regional transportation network and were concerned that an inability to act would reduce mobility and hinder regional economic growth.

8.7 Agency-Vendor Relations

The risk management terms and conditions of the RFP presented complications to agency-vendor relations. The initial RFP required responders to post a $10,000,000 guarantee via letter of credit. Three teams responded to the initial RFP and two of them were deemed viable. It is likely that other potential bidders did not submit proposals because they were not able to post the required guarantee. The final contract requires the vendor to post ten million dollars in Performance Security at various milestone points in the contract. In order to do so, the vendor may utilize a letter of credit, performance bond or retainage.

The agencies have noted that use of a vendor from a different part of the world introduces communications lags due to time zone differences. The vendor opened a satellite office in Seattle, but some of these delays persisted because the local vendor staff did not always have the expertise or decision authority required for specific issues and, in these cases, needed to communicate with its headquarters. The vendor’s training and technical personnel are in Australia, and access to them has been controlled through the vendor’s local office. Installation issues that should have been addressed directly by technical vendor staff on site have been handled in a very slow process of exchanging written communication because these staff are not on site. Also, the ILA designates the Contract Administrator as the main point of contact between the agencies and the vendor. This clearly has value in managing the work of the vendor but makes it more difficult for the individual agencies to get their needs met as they could be, if they were each able to work directly with the vendor. These issues have been recognized and steps taken to try to resolve them, but the inefficiencies associated with geographic distance and the inability of the agencies to interact directly with the vendor remain problematic.

Other problems in the project development can be attributed to imperfect communications. One problem that set back the design schedule concerned the design documents. The vendor usually uses two design phases, a Preliminary Design Review (PDR) and a Final Design Review (FDR). For the RFC Project, the partner agencies requested an additional review phase, the Conceptual Design Review (CDR), to occur before the PDR. Apparently, the requirements of the CDR were not effectively communicated because the design document produced by the vendor for the CDR generated an unexpectedly large number of comments from all of the agencies. The process of combining the comments from all seven agencies into a cohesive, non-redundant document was time consuming. In addition, the vendor needed more time than anticipated to respond to each of the comments. It seems that the volume of comments arose from a misunderstanding regarding the level of detail required for a CDR.