7. PROJECT MANAGEMENT

7.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses two specific issues relating to management of the RFC Project: the contract administration plan, and information flow management.

7.2 RFC Organization and Contract Administration

The organizational approach used in the Central Puget Sound RFC Project is based on a “consensus” model, compared with the approach used in the TransLinkâ Bay Area fare card project that can be said to be based on an “efficiency” model. Which approach or model to follow is a matter of regional choice, but the unique attributes and consequences of each need to be carefully considered. In the case of the RFC Project, an efficiency model might have resulted in King County Metro having a lead role, perhaps to the extent that it would have defined the technical and institutional makeup of the project and tested the system on its fleet even before any of the other agencies agreed to commit to a partnership. This was not an approach the other partners were willing to follow, and King County Metro did not try to promote this approach given the significant liabilities associated with it.

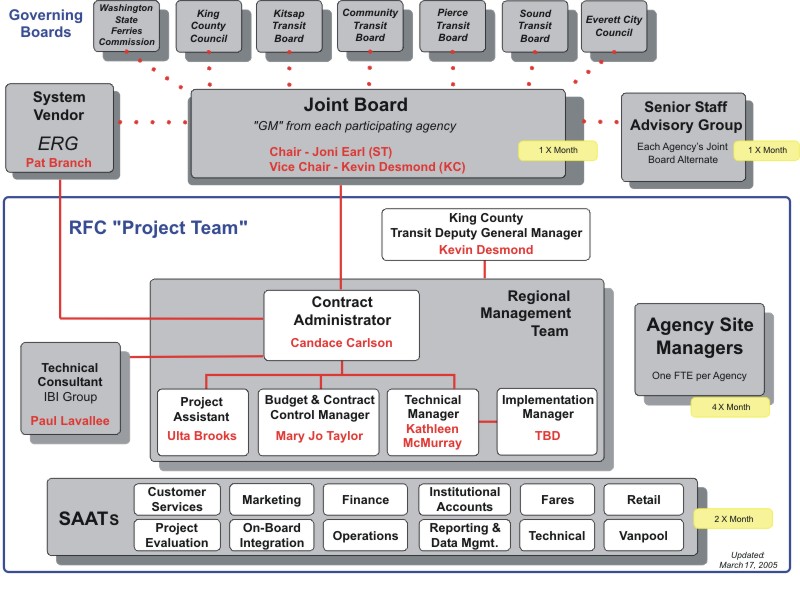

The RFC Inter-Local Agreement (ILA) includes a Contract Administration Plan that establishes the RFC Project management organizational structure (Figure 4). Overall governance of the RFC Project is vested in a decision-making Joint Board composed of high-level managers from each of the partner agencies. The Joint Board adopted the principle of one vote for each partner, regardless of size, with unanimity required for most decisions. The Joint Board oversees the performance of the Regional Management Team (the Regional Team) that provides guidance to the partner agencies for RFC Project implementation, as well as the oversight and management of the vendor and other consultant contracts.

The Contract Administrator heads the Regional Team and has day-to-day responsibility for managing the other members of the Project Team. The Administrator coordinates project planning in collaboration with the Regional Technical Manager, a Budget and Contract Control Manager, and a Project Assistant and is supported by a technical consultant to the project. The Contract Administration Plan specifies the detailed responsibilities of the Contract Administrator. These include, among many other things, monitoring contractor performance, reviewing deliverables, monitoring project compliance with federal and state laws, and maintaining documentation files relevant to the contracts.

Figure 4. Regional Fare Coordination project organization chart.

7.3 Consensus Approach to Regional Management and Decisions

The “consensus” model offers a variety of benefits and costs. It requires that each agency take an active role in reviewing system design decisions and documents and reaching agreement on vendor directives. This clearly multiplies the amount of work required to develop the project, and makes the work more complicated because of the need to reach consensus among a variety of agencies with differing concerns.

Notwithstanding these time requirements, the “consensus” model worked well throughout the initial stages of the project development process, during which high-level aspects of the system design were agreed between the partner agencies and with the system vendor. However, these stages of the process were characterized by schedule slippage and by a very heavy and unanticipated workload on the partner agency staff. As the project moved towards preparing and reviewing the detailed final design documents, these problems were exacerbated, to a point where the continued viability of the initial organizational arrangement was questioned by some of the partner agencies.

The Interlocal Agreement does not provide for a project manager position, and only mentions project management responsibilities of the Contract Administrator in general terms. In effect, there are seven project managers, represented by each of the partner agencies’ Site Managers. The Contract Administrator and Site Managers have concentrated on administering the complex and detailed vendor contract. While the Regional Team includes a Technical Manager responsible for schedule management and agency coordination on all technical matters, there has been a lack of focus on standard project management activities involving project planning, scope, schedule, direction, and guidance of the SAATs. The partner agencies have explored organizational options for strengthening the project management function. Possibilities considered have included increasing the involvement and authority of members of the Joint Board, or hiring a consultant to serve as project manager. The Regional Team has worked much of the time with limited staff, and only recently received Board approval to fill an additional position of Regional Implementation Manager to help with their intense workload. The importance can not be overstated of establishing a regional team that has adequate staffing and resources to support the extensive regional coordination and leadership workload of a project of this magnitude.

Agencies in the Central Puget Sound region are strongly predisposed toward regional collaboration, but of course each RFC Project partner is also dedicated to meeting the needs of its own agency and customers. Given the differences in the characteristics of each agency and its customer base, the consensus model has required considerable time to allow for each partner to express its opinions and needs and work those through a collaborative process toward acceptable compromises and decisions. Nevertheless, the partner agencies believe that the end result will be worth the extra time and effort and, given the strong sense of regionalism in Puget Sound, it is unlikely that a regional participant program across all of these agencies would have been feasible under any other organizational approach.

Locations considering implementing a regional fare card program will want to consider the different organizational approaches that have been tried in other programs of this type and will want to understand and balance the values that each partner brings to the regional entity. Efficiency could potentially be gained by vesting program leadership in one of the partner agencies. However, that would require the other agencies to accept an arrangement with which they and their customers might not be comfortable over the long run. The alternative approach, adopted in this case, seeks to assure that every partner’s interests are given equal weight in the final decisions and arrangements. While this process is more time consuming, costly, and demanding of all partners in the near term, it fosters pride and ownership in the resultant regional system over the long run.

Lesson: A Consensus Approach to Management and Decision Making

- Allow each partner an equal say in decision-making in the regional partnership to build trust, understanding and buy-in by ensuring that no one agency will dominate the process.

- Build on past examples of good institutional working relationships and emphasize the values associated with a philosophy of regionalism over individual agency self-interest.

- Be aware of trade-offs associated with the consensus model. A structure in which each agency is equally involved in decisions and policy will almost certainly entail more staff time and cost than a structure with one lead agency.

- Establish a formal agreement, endorsed by the highest levels of management in each agency, that specifies roles, responsibilities and organizational structure in support of the consensus model. The Interlocal Agreement served that purpose for the Central Puget Sound RFC Project.

- Adopt strong project management procedures that allow for clear goals, plans and schedules to help keep the project on track, and provide adequate staffing and resources to a regional team to coordinate and lead a project of this magnitude.

- Seek a balance between attention to management of the vendor contract and to management of the project development process.

7.4 Information Flow Management

A considerable amount of communication between the vendor and the Project Team is required to finalize the RFC system design, and to develop the system hardware and software according to the design. The ILA requires that all communications between the Project Team and the vendor pass through a single point of contact; in practice, the Contract Administrator has delegated this function to the Regional Technical Manager. These communications are formalized in the Request for Information (RFI) process.

RFIs are issued by both parties. Generally, the purpose is to ask for guidance on matters that arise during system development. Upon receiving an RFI, the Regional Technical Manager forwards it to the Project Team members (SAAT members or Site Managers) most able to draft an answer, along with a deadline for a response. The prepared response is reviewed and amended as necessary by the Regional Team and Site Managers before being sent back to the originator of the RFI.

Note that RFIs are not binding, and that decisions reached via the RFI process about system features or design aspects do not become definitive until the final design review.

There has been a large volume of RFIs, and the Project Team found it necessary to develop a system to track the flow of information. Each RFI is given a unique numeric identifier in a database, and its status is updated on the project’s restricted access web site and followed to make sure that a response is generated.

In practice, the RFI process has been found to be somewhat cumbersome. While the single point of contact ensures that the Project Team will provide the vendor with consistent messages, it also constitutes a communications bottleneck. Furthermore, several rounds of time-consuming back and forth communication are sometimes required for both parties to be clear on what is actually being asked. The RFI process has been augmented with workshops that provide a venue for RFC Project Team members to interact and work directly with vendor specialists. Both agency and vendor personnel have emphasized the importance of these face-to-face discussions.

7.5 Managing Time and Complexity

The RFC Project is technically, procedurally and organizationally very complex, and this level of complexity places substantial demands in terms of time and effort on the participant agencies and their staffs. One of the RFC Site Managers stated the challenge succinctly: “A regional fare card project will be more difficult and complex than you can imagine.”

Impacts of the RFC Project complexity on partner agencies have taken several forms. Most of the RFC Site Managers were hired or assigned relatively soon after the establishment of the RFC Project to lead their agency’s participation in the project. Only one of the Site Managers had a full time job in the agency when asked to serve as Site Manager, and this situation created a sense, for a while at least, that the individual had to work two jobs. Part-time agency staff also feel the stress of having to shoulder a lot of additional responsibility.

Several factors contribute to the extensive time commitment required from RFC partner agencies. Because the decision process is based on consensus, considerable emphasis is placed on process. Many of the partner agencies said they would prefer to keep the process simpler, though they do not want to give up the consensus model. Contributing to this degree of complexity are the technical and legal issues that have to be worked out, and the elaborate RFI process.

The vendor produces very detailed design documentation that must be cycled through each agency for careful review and comment. These documents number in the hundreds of pages and their review requires technical, legal, and other types of expertise on the part of the agencies and Regional Team. Processing this kind of documentation, and then seeking resolution to the important issues that are identified through the review process, takes significant amounts of staff time and has resulted in unanticipated extensions to the project schedule.

The Site Managers from each of the seven partner agencies, along with selected members of their agency staffs, must attend frequent meetings of the RFC team in order to stay abreast of the project and effectively manage it on behalf of their agency. Site Managers typically attend several meetings a week in Seattle, which entails significant travel time for those coming from outlying agencies. They also attend many SAAT meetings (some managers attend every one) because they feel this is an important way to exercise managerial control over key decisions and keep up on the flow of information. Time spent away from their agency is time they are unavailable to participate in its regular business, and this has created frustration and problems for agency management as well as the RFC Project Site Managers.

Many agencies consider the project milestone schedule to be excessively tight. The burden of a demanding schedule was exacerbated in some cases by an initial lack of organization. Examples include some SAATs that operated with no work scopes and limited guidance and coordination, and the lack of a clearly identified project management role in the Interlocal agreement. Another consequence of the tight schedule is the perception by participants is that there is too much pressure to make decisions quickly, without sufficient time to review and deliberate.

Elements of the RFC Project’s organizational structure duplicate in some respects the internal structures in some of the partner agencies. For example, King County Metro has internal committees that are similar to many of the RFC Project’s SAAT committees. The smaller partner agencies on the other hand tend not to have comparable organizational components that could constitute an experience base for the RFC Project. In circumstances where there is overlap, it would be useful to seek ways to achieve synergies and efficiencies.

Some agency managers said that they were concerned that the intense day-to-day pressure of schedule and issue resolution was precluding opportunities to give adequate attention to future-oriented visionary thinking about the project and its implications for both the region and the individual agencies.

From a staffing point of view, the partner agencies say that they have had problems getting the best-qualified staff to work on the RFC Project because staff members are assigned to other work or the needed skills are hard to find in the agency. Also, a significant staff time burden has been experienced by the various subject area experts within the agencies who have had to review designs, attend SAAT meetings and prepare their subject areas for the new system. These subject area experts have continued to reside in their home divisions, such as finance, operations, and maintenance, rather than be assigned to an agency project team, and few if any of them has been backfilled to make up for the extraordinary time they have had to put into the project. The impact of this has been greater on the smaller agencies that have just as much material to review and the same number of meetings to attend but with far fewer agency resources available to them. As a result these smaller agencies have ended up having to be very selective about what elements of the project they are actively involved in. In actual fact the agencies have tended to rely on each other to review aspects of the project for which a particular agency has expertise or a high level of interest. For example, although the employer program will apply to all agencies, KCM has taken the lead in reviewing the design of this program because of its importance to the agency.

This is a very large project and it is bound to encounter unforeseen problems and challenges. One manager mentioned that no project of this size can expect to get everything right at the outset. It is critical to be flexible and willing to change as circumstances evolve. Because of the project’s size and complexity, its schedule is entwined with those of other major projects also underway in the partner agencies (e.g., radio systems; smart fare box; GPS/AVL; automatic passenger counters; point-of-sale system for ferries). Schedule slippage in one project can affect the others, through both resource implications as well as technical integration requirements. Organizations undertaking a regional fare card project must fully understand these inter-dependencies from the beginning if they are to avoid costly problems. Finally, fare card systems that require some degree of customization will involve more time and complexity than a purely off-the-shelf system. In the case of the Central Puget Sound RFC Project, the system is being procured from a vendor who is making modifications to existing devices and software to accommodate the regional business and operating rules and the need to integrate this system with existing third party hardware. Agencies considering a RFC Project should carefully consider these time and effort implications when choosing between customized and off-the-shelf systems.

Lesson: Manage Project Time Demands and Project Complexity

- Each partner agency should assign a full time Site Manager, having the requisite project management and substantive skills and experience, and charged with the sole responsibility of managing its program implementation. Assume that it will take one FTE to carry out the fare card project management responsibilities. It is helpful for the Site Manager to have worked for the agency long enough to be able to represent its interests effectively in regional meetings and discussions. Consider reassigning the Site Manager’s prior responsibilities to other staff so that he or she can focus exclusively on the regional fare card program.

- Recognize in advance that an iterative, consensus-based process is very time consuming and plan accordingly.

- Anticipate the large amount of time that document review will take for all the parties involved in the project. In scheduling, allow additional time as a safety factor to accommodate those activities and to avoid schedule slippage.

- In planning for participation in a regional fare card program, understand in advance that considerable time will be required to attend meetings, and that this will compete with other agency demands on a Site Manager’s time and attention.

- Provide adequate time in the schedule to accomplish all the work that needs to be done, and provide for project management oversight and guidance to gain efficiency and coordination across all the tasks and work groups.

- Take account of the size and experience of each agency to help “level the playing field,” and offer extra support where it is needed.

- Look beyond the immediate demands of the project’s day-to-day activities and factor into the regional fare card plans the long-term needs of each agency and the region.

- Larger partner agencies are more likely to have depth in staffing and skills and should be able to shoulder a commensurately larger share of the work of the regional partnership. It is important to seek ways to meet the staffing demands from the regional fare card project for the smaller partner agencies in particular.

- Above all, be flexible and willing to make changes during the development of a successful regional fare card project, as it is impossible to anticipate all the issues and challenges that will arise.