| Environment |

|

|

|

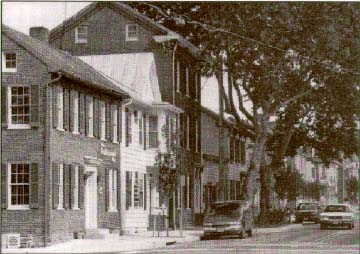

EAST MAIN STREET RECONSTRUCTIONWestminnster, MD | |

|

|

BACKGROUND/PURPOSE East Main Street has changed little since Jeb Stuart's cavalry pursued the 1 st Delaware down its dusty way on June 29, 1863, in a prelude to Gettysburg. Pavement has covered the dust, sidewalks have replaced boardwalks, and utility lines have taken the measure of the maturing trees. In 1990, Westminster had more than doubled its population, to 13,582. At the perimeters, shopping malls beckoned.

The very age that had made downtown Westminster a National Register Historic District was slowly eroding its attractions. Rains lingered in puddles, because there was no storm drainage. Countless repavings had raised the street's center, resulting in slanted parking spaces that caught car doors on curbs. Porches, stoops, and utility poles encroached onto narrow, cracked, and cavedin sidewalks. Vacant stores and office spaces attested to the decline. After more than a year of planning and design, the Maryland State Highway Administration's consultants completed their drawings for East Main Street's revitalization in October 1990. In May 1991, the city had three new city council members, and the administration and public balked at a 12.2 mwide (40ft) roadway of two 3.6m (1Zft) travel lanes and two 2.4m (8ft) parking lanes. That scheme would have removed 42 trees, some dating back to the last century. The old roadway was 10.4 m to 11.9 m (34 ft to 39 ft) wide. The new sidewalks would have an average width of 1.5 m (5 ft), as cramped as the old ones.

ACTIONS TAKEN TO RESOLVE ISSUES In March 1991, the Maryland DOT appointed a 10member committee to come up with ideas, and the State sent designers to help this task force realize their ideas. By December 1992, after numerous sessions and hearings, the new plan was complete. The State paid for the extra design work, which amounted to $199,523. Construction began in April 1993 and, in December 1994, the 1.5kmlong (.93mile) project was open to traffic. The desire to avoid removing 42 trees had been foremost, thus the total pavement width was reduced from 12.2 m (40 ft) to 11.0 m to 11.6 m (36 ft to 38 ft). In addition, to give trees breathing room, sections of curbing were extended 1.8 m (6 ft) into the parking lane of the roadway. In all, 34 of the 42 mature trees were saved, and 104 trees were added. Metal grates around each tree space keep the soil porous. The city paid the $36,000 planting and landscaping costs. Sidewalks were widened from 1.5 m to 3.0 m (5 ft to 10 ft), and in some areas where there had been no sidewalks, there were now 1.2m to 1.5m (4 ft to 5 ft) walkways. There are 11 pedestrianfriendly areas with landscaping. Existing telephones and mailboxes remained. Concrete payers that look like brick add variety to these areas and crosswalks; they also echo the brick of the many historic buildings. Concrete curbstone provides a continuity of texture.

Traffic lanes were reduced in width from 3.6 m (12 ft) to 3.4 m and 3.0 m (11 ft and 10 ft), and transportation staffers feel they could have been as narrow as 2.9 m (9.5 ft), because traffic moves slowly. Often, inches are crucial to tree growth. The speed limit is 40 kph (25 mph), designed for 48 kph (30 mph). Parking lanes remain 2.4 m (8 ft) wide, and each space is marked with a "T" to make more efficient use of the space available. The designated spaces make up for an 11percent loss of parking space, the equivalent of 19 onstreet spaces, used for existing and proposed tree planting. The original design, however, would have required the loss of 35 spaces, a 20 percent loss.

Important to Westminster's heritage, "street furniture," such as boot scrapers, hitching posts, and entranceways, was conserved. Archaeological digs during the construction phase unearthed a boundary marker, vault, coal chute, and well, items which can be preserved. LESSONS LEARNED Not all goals were accomplished. Utility lines did not go underground, because the cost would have been $3 million plus added costs for new individual connections. Another route would have been the placement of utility lines aboveground, although in the rear of buildings. Utility poles are now fewer but lamer.

In all, the city and State learned that citizen involvement at the beginning saves time and that the dollar cost for improved design was $199,523in a project that totaled $3,150,828. Realtors estimate that, because of the increased demand for downtown retail and office space, the added cost of the project will be made up in 4 years' revenues to the city. Current and future streetimprovement projects will involve residents and designers at initial stages and, as the construction takes place, flyers will tell people what is going to be done, when, and where.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|